Education

Flourishing in Life Does Not Require Straight A’s

Attending a college with no tests or grades rewired my brain to love learning.

Posted December 24, 2018

In December of 2018, I read two New York Times education-related opinion pieces (“What Straight-A Students Get Wrong” and “Are Straight A’s the Road to Success?”) as well as a post by fellow blogger, Peter Gray, “Back Off: It Doesn’t Matter What College Your Kids Attend." These three articles have overlapping themes and provide valuable food for thought—especially as the parent of an 11-year-old who will be applying to college sooner than I can imagine.

This post is in response to the abovementioned articles and offers some autobiographical examples of how attending a relatively easy-to-get-into college with no tests or grades has influenced the trajectory of my life in the three decades since I graduated from Hampshire College in 1988.

On December 22, the Times published a letter to the editor from Raphael Sherak, who is an alumnus of my alma mater. Sherak writes,

“Several colleges, including Hampshire College, assess students with narrative evaluations instead of letter grades. Narrative evaluations shift the focus from academic achievement to learning and growth. I should know. My perfectionism and pursuit of A’s led me to overextend myself and drop out of high school. I eventually attended Hampshire College, where I was able to focus my studies on problems I wanted to solve, questions I hoped to answer and skills I wished to learn. Since being freed from grades, this high school dropout has gone to both medical school and the Harvard School of Public Health.”

Sherak’s letter resonated with me. Although I didn’t drop out (or flunk out) of high school, I was a solid C- student and my SAT scores were abysmal. Thankfully, when it came time to apply to college, my mother (who is from Western Massachusetts) knew about a small liberal arts school in Amherst called “Hampshire College” that didn’t look at SAT scores as part of their admissions process. The best part about Hampshire College (for me) was that professors didn't make students take tests and there were no grades.

As Sherak references in his letter to the editor, at Hampshire College, every student is encouraged to take whatever classes pique his or her curiosity and to tailor a unique curriculum. Oftentimes, academic studies on campus are augmented with off-campus learning experiences and internships.

Yesterday, I realized how much I've benefited from this educational approach since college graduation after reading the following paragraph in Peter Gray's most recent, "Freedom to Learn: The roles of play and curiosity as foundations for learning," post:

"Another survey, of 30,000 college graduates by Gallup Poll and Purdue University (here), assessed the degree to which the graduates were, by their own reports, engaged at work (enthusiastic and committed to their work) and thriving in their personal lives. They found no significant relationships at all between these ratings and the type of college attended. Whether the college was public or private, large or small, highly selective or less selective made, on average, no difference on any these measures. However, the experiences they reported having in college did make a difference. Regardless of what kind of college they attended, those who recalled a professor who cared about them as an individual and encouraged their aspirations, or who had a job or internship in college that allowed them to apply what they were learning, had significantly higher ratings of engagement and thriving after graduation than those who did not. According to this study, it matters not what type of college you go to but does matter what you do there."

The Hampshire College philosophy echoes Gray's worldview on education. As their mission states, “At Hampshire, your education focuses on personalized, independent work, close collaboration with faculty, and the belief that the questions that drive you should drive your education.” At Hampshire, there are no "off-the-shelf" majors; students' college education is based on individualized areas of concentration that they feel passionate about and want to explore more in depth.

As an autobiographical example of the Hampshire ethos in action, I’ve always loved pop culture and Top 40 music and never thought of myself as having so-called "book smarts." Unexpectedly, as a college student, I became interested in meditation, Eastern culture, and yogic philosophies regarding the mind-body connection. These disciplines might seem incongruous, but at Hampshire, I was able to meld these personal interests into my academic curriculum in three stages.

First, I spent a semester as an intern at Entertainment Tonight with Mary Hart in Hollywood. Second, I did another internship at Billboard magazine in Manhattan. Third, I traveled to India—where I lived with a local family in New Delhi—while doing "shoe-leather" reporting and an eyewitness investigation of rampant video and audio-cassette piracy that the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) and Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) were desperately trying to curb in the 1980s.

My final “Division 3” project at Hampshire brought all of these learning experiences and coursework together in a thesis about the impact bootleg copies of Disney movies, Warner Bros. music, and other Western media were having on traditional indigenous culture and day-to-day family life in India.

As mentioned earlier, Hampshire professors give students detailed narrative evaluations instead of grades. Not being graded by a teacher completely changed how I view learning. It makes sense that “Non Satis Scire” (to know is not enough) is the Hampshire College motto. (See, “Cerebro-Cerebellar Circuits Remind Us: To Know Is Not Enough.")

Hampshire students never have to memorize crystallized knowledge or cram for an exam; the school’s pedagogy promotes fluid intelligence by encouraging students to connect-the-dots between seemingly unrelated knowledge in new and useful ways.

In 1965, long before we had Google search engines or swaths of data on the internet at our fingertips, the Hampshire college founders prophetically understood that flourishing across a lifespan in the real-world is the ultimate open-book test. Cramming your head full of facts is useless if you can't problem solve or apply this knowledge in fresh and novel ways.

The Hampshire approach to learning turned my brain into a sponge that remains thirsty to absorb as much diverse anecdotal and empirical evidence on a daily basis as possible.

My intellectual curiosity to explore original ways of thinking also fostered my adventurous mindset and "openness to experience" as an athlete. After graduating from college, I was eager to explore different continents as an Ironman triathlete. Additionally, in the 1990s, I was one of the only “out loud-and-proud” gay athletes competing internationally on the stereotypically-straight Ironman racing circuit.

After doing Ironman races for a few years, there was no mystery. I started to get bored. Once I "knew" the ins and outs of regular distance Ironman races, the experience of running, biking, and swimming a total of 140.6 miles began to feel kind of ho-hum. So, I decided to explore unknown territory by becoming an ultra-marathon runner and competing in Triple Ironman races (7.2-mile swim, 336-mile bike, 78.6-mile run done nonstop).

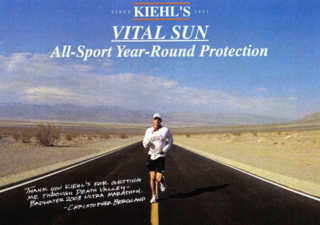

Not to sound too braggadocious, but I flourished in these rarefied athletic events. In many ways, I think my athletic success in “freakish” long-distance races was tied to the mindset that got hardwired into my brain at Hampshire. In my 30s, I won the Triple Ironman three years in a row; as an ultra-marathoner, I finished the Badwater 135-mile Death Valley race twice. In 2004, I broke a long-distance running Guinness World Record.

Ever since graduating from college in '88, I've lived by Kurt Vonnegut's creed, "I want to stand as close to the edge as I can without going over. Out on the edge, you can see all kinds of things you can't see from the center."

Of course, because I only attended one college—and Hampshire didn't have any tests or grades—there's no way of knowing what would have happened to the trajectory of my life if I'd attended a traditional college that encouraged students to stick closer to the path most traveled and get straight A’s. Would I have gone on to become a maverick who broke gay stereotypes as a trailblazing athlete? I will never know for sure... But I have a gut feeling that if I'd been encouraged to always aspire to societal norms of "success," I probably wouldn't have pursued adventures that took me far from the mainstream.

After retiring from professional sports in my 30s, my disposition to explore new horizons and break-the-mold drove me to write a quirky self-help book, The Athlete’s Way: Sweat and the Biology of Bliss (St. Martin’s Press).

This multidisciplinary book is about athletic mindset, neuroscience, cerebellar function, superfluidity, and peak performance in both life and sport. The manuscript (completed in 2005) presented pioneering ideas about nonmotor functions of the human cerebellum at the beginning of the 21st century, almost a decade before cerebellar functions became a trendy topic. (see, "7 Awe-Inspiring Exhibits of Superfluidity in Action," "The Split-Brain: An Ever-Changing Hypothesis," and "Why is the Cerebellum Making Headline News?")

Even though I was a straight C- student in high school, I was able to get a book deal with one of the Big Five publishers as an adult. After publishing my first book, ASICS sneakers hired me to write a blog for their global brand as an international “Motivator.” After writing that blog for a couple of years, I had enough street cred and blogging experience to take on the mantle of "The Athlete's Way" blog you're reading now.

The bottom line: I'm living proof and "Exhibit A" that flourishing across a lifespan does not require getting straight A's in high school. I firmly believe that if I can do it—you can, too!

That said, there is an important caveat: Having the financial resources to attend a private college, travel abroad, and afford room-and-board in tony zip codes (NYC, LA, SF, etc.) while doing non-paying internships is a luxury that isn't a feasible option for everybody. Nevertheless, hopefully, this post will inspire people from all socioeconomic backgrounds to explore affordable collegiate learning experiences that take the emphasis off solely striving for a perfect 4.0 GPA.