Flow

What Driving Force Helps Us Go from "Flow" to Superfluidity?

Deconstructing what triggers ecstatic bursts within regular states of "flow."

Posted October 14, 2018

Like thousands of people around the globe, in 1990, I read Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi's seminal book, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Learning about flow and how-to hone in on a sweet spot between anxiety and boredom — called the "flow channel" where your level of skill perfectly matches the degree of challenge — was life-changing for me. I was 24 years old when I first grasped the concept of flow. Over the next decade, I spent a few hours every day purposely seeking flow while running, biking, and swimming as a full-time triathlete. Because I spent so much time in a state of flow every week, it became clear to me that within the “flow channel” there were episodic bursts that sent shivers down my spine, gave me goosebumps, and felt like pure bliss.

Regular flow felt good, but these random moments within a flow state when my mind, body, and brain were completely harmonized and connected to the world around me were absolutely ecstatic. The word “ecstasy” in Greek means to “stand outside oneself.” During these transcendent moments, my ego seemed to dissolve and my entire being melted into a type of “universal connectedness” where “I” and “the other” became one. These moments were fleeting. And if I tried too hard to hold onto this exuberant feeling — or became overly excited by saying something to myself like, "OMG. It's happening!! It's happening!" — the ecstatic feeling would slip through my fingertips like sand from a clenched fist.

I’d experienced this phenomenon of feeling "one" with everything and everybody around me during adolescence when I took psilocybin with some high school classmates in the form of psychedelic mushrooms. As an adult, pursuing similar mind-altered states of consciousness that I’d experienced on psilocybin as a teenager (without the use of drugs) became my holy grail. And, I discovered that ultra-endurance aerobic exercise was a vehicle that could take me to this special place.

Unfortunately, I didn’t have a name to describe this second-tier of flow until one day when I stumbled on a BBC documentary called “Absolute Zero” which showed lab clips from the 1930s of helium becoming a “superfluid” that existed without any friction or viscosity and could do amazing things like leak through the bottom of a glass beaker or climb walls to escape its container (as seen in the video clip below.)

In my mind, the term “superfluidity” is perfect for describing what it feels like to have one's thoughts, emotions, and actions synchronized with absolutely zero friction, viscosity, or entropy. This physics-based terminology also captures how someone can go through a phase transition such as flow-to-superfluidity, back-to-flow, and then from flow back to the "crystalline order" of the work-a-day world.

Unfortunately, superfluidity happens in short bursts and is very elusive. That said, the prime driving force that motivated me to spend up to 12 hours a day training fanatically was that I became like a junkie trying to get a "superfludity" fix who was akin to a religious zealot seeking epiphanies via aerobic exercise. Notably, the orgasmic bursts of superfluidity within the flow channel are short-lived and from my experience tend to occur during extensive periods of sustained flow. As a simple analogy: Flow is to superfluidity as coitus is to orgasm.

Flow: Superfluidity :: Coitus: Orgasm

“Superfluidity: Chase Your Bliss” is the title of the last chapter in my 2007 book, The Athlete’s Way: Sweat and the Biology of Bliss. Someday, I'll write a book called Superfluidity . . . But I can't do that yet, because I’m still trying to connect the dots and figure out when, why, and how everybody can learn to experience this phenomenon in his or her daily life.

For some references: In addition to “Flow” by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, two other books that have significantly influenced my conceptualization of “superfluidity” are Ecstasy in Secular and Religious Experiences (1960) by Marghanita Laski and The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature (1902) by William James.

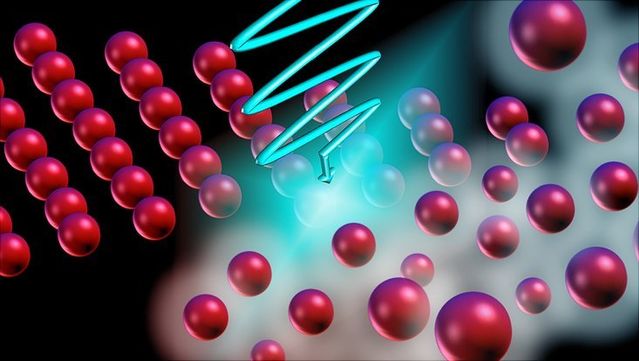

That being said, this morning I was prompted to write this blog post after reading a press release from the University of Hamburg, “Disrupting Crystalline Order to Restore Superfluidity,” which describes how researchers could help a so-called “underdog” transition to an elusive, but optimal phase (in this case superfluidity) by adding a little bit of “drive.”

The Universität Hamburg statement about Professor Ludwig Mathey and his team's research is beautifully written and brings a potentially eye-glazing discussion about physics to life using real-world analogies. Please take a few minutes to read the press release PDF here.

The research question that prompted the latest study on superfluidity at the University of Hamburg: “What if you could disrupt the crystalline order so that the superfluid could flow freely even at temperatures and pressures where it usually does not?” The statement says:

“A team of scientists led by Ludwig Mathey and Andreas Hemmerich from the University of Hamburg have disrupted crystalline order in a quantum system in a controlled manner by shining light on it that oscillates in time at a specific frequency. Physicists use the term “driving” to describe this kind of periodic change applied to the system – an action performed by the churning blades in a slushy machine. Their work, published in Physical Review Letters, identified a fundamental mechanism for how a typical system with competing phases respond to an external periodic driving.”

As someone who has been thinking about practical ways to create “superfluidity” in real-world situations, having the new terminology of “driving” (or "drivers") that can help push a quantum system into a superfluid state triggered an aha! moment for me.

Because my experience with superfluidity is completely anecdotal, this morning while I was out for a long jog, I created a timeline of when-where-and-what I was doing when I realized there were certain “drivers” that helped me go from a regular flow state to a state of superfluidity. As a side note: While reading my first-person narrative below, please think about potential “drivers” in your life that take you to another stratosphere when you’re inside the flow channel and share them in the comments, if you have time.

10 Potential “Drivers” That Might Help Us Experience Superfluidity (based on life experience) by Christopher Bergland

1. Nature-inspired awe and a sense of spiritual connectedness to something much bigger than oneself that creates the “Small Self.”

2. Religious-themed music (e.g., "Morning Has Broken," "Like a Prayer.")

3. Time-capsule like “Proustian” scents linked to positive what-when-and-where memories.

4. Reciting poetry and verse (e.g., "The Book of Revelation")

5. Romantic-era visualizations of yourself in a painting (e.g., Caspar Friedrich)

6. Optimal cerebro-cerebellar functional connectivity & synergy of all four brain hemispheres

7. Neurophysiology created by sustained aerobic exercise (e.g., tonic levels of brainwave synchrony, neurochemicals, and hormones)

8. Psilocybin

9. Psychoanalysis (e.g., The White Institute)

10. Diversifying experiences and schema violations that disrupt “Normality"

Looking at this Caspar Friedrich painting never fails to remind me of the “quintessence” of superfluidity. There’s a certain aura to this landscape that allows me to visualize myself somewhere on the canvas from a birds’-eye-view vantage point that creates a “small self” associated with experiencing awe in nature. During these "wow!" moments you realize there’s something much bigger than you out there. I first experienced a sense of spiritual connectedness in 1975, when I was 9 years old and moved from the Upper East Side of Manhattan to a rural limestone farmhouse in Lebanon, Pennsylvania surrounded by luscious green rolling hills and cornfields.

In the mid-1970s, I started attending Mennonite church every Sunday and listened to the vinyl 45 of “Morning Has Broken” by Cat Stevens on a daily basis. I also had a horse named Commander, who my parents let me run wild; I was free to ride anywhere I felt like going in and around Lebanon. The combination of galloping full speed on Commander through the cornfields when the sun was either rising or setting while humming “Morning Has Broken” is probably when I first began to figure out "drivers" linked to dialing-up feelings of superfluidity on demand.

Another time I began experiencing superfluidity regularly was in the early 1990s, when I started bi-weekly psychoanalysis at the White Institute on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Oftentimes, I'd go for a really long jog in Central Park after analysis. The combination of prolonged aerobic exercise and being in Nature after “laying on the couch” made me ripe for superfluidity.

Around this time, the AIDS epidemic was decimating my local community in the 10014 zip code and around the world; this was a traumatic diversifying experience that upended normality in my life and filled me with crippling anxiety. Fortuitously, after seeing Madonna perform the “Blond Ambition" concert as an amfAR benefit dedicated to her friend Keith Haring (1958-1990), my joie de vivre and ability to face obstacles as "challenges" (not just "threats") were emboldened. Luckily I was able to get a bootleg copy of the concert from my friend David who owned RebelRebel records on Bleecker Street. I’d play the live version of “Like a Prayer” on my Walkman all the time. This song became my ultimate anthem and "driver" for taking flow states to a higher plane.

I also had the VHS of “Truth or Dare” with the video clip (above) in which Madonna and the entire troupe of dancers seem to create a collective moment of Superfluidity beginning at the 4:58-minute mark through the end of the performance.

Before every Ironman triathlon or other ultra-endurance challenges, I'd put on a few dabs of patchouli, mixed with Coppertone, and my mom's signature scent "Eau d'Hadrien" while listening to the live version of "Like a Prayer" at full-blast volume. The combination of this religious-themed music and encoded olfaction seemed to be a powerful driver that increased my odds of experiencing superfluidity during a race and going on to "win." (For more see, "Mastering a Mindset of Loving to Win Without Hating to Lose.")

Lastly, I have a William James-inspired theory from his "Gospel of Relaxation" essay that when you “Unclamp” your prefrontal cortex by going into the “zone” — and avoid overthinking for extended periods of time while working out — that it can facilitate optimal cerebro-cerebellar functional connectivity between all four brain hemispheres. I have a hunch that these brain mechanics may somehow be a “driver” for superfluidity. (For more see: "Mapping the Human Cerebellum Reframes Whole-Brain Functions.")

As you can see, my conceptualization of superfluidity is very much a work in process. Stay tuned for future blog posts in which I’ll do a deeper dive into other potential driving forces that can help us create superfluidity in our day-to-day lives.

References

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. (1990) Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper & Row.

Laski, M. (1961). Ecstasy in Secular and Religious Experiences. Los Angeles, CA, England: Jeremy P. Tarcher, Inc.

James, William (1902). The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature : Being the Gifford Lectures on Natural Religion Delivered at Edinburgh in 1901-1902. New York; London :Longmans, Green.

Jayson G. Cosme, Christoph Georges, Andreas Hemmerich, and Ludwig Mathey. "Dynamical Control of Order in a Cavity-BEC System." Physical Review Letter (First Published: October 11, 2018). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.153001