Alcoholism

The Neuroscience of Binge Drinking

Neuroscientists have pinpointed the brain circuits that control binge drinking.

Posted April 30, 2016

Michael Phelps—the most decorated athlete in Olympic history—was recently asked by Matt Lauer, “So, do you think you’re an alcoholic?” In response, Phelps said, “I don’t know. I honestly don’t know. I know I probably have moments where I have gone off the deep end where I shouldn't."

In 2014, Phelps put his swimming career on hold and checked into rehab after his second DUI. His alcohol level at the time of his arrest was .14 g/dL, which is nearly twice the legal limit. Approximately 10-15 per cent of the population is alcohol dependent. Binge drinking costs the United States more than $170 billion annually.

The National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) defines binge drinking as a pattern of drinking that brings blood alcohol concentration (BAC) levels to 0.08 g/dL. This typically occurs after 4 drinks for women and 5 drinks for men—in about 2 hours.

What Drives Somebody to Binge Drink?

Obviously, the specific reasons for binge drinking will always vary widely from person to person based on many factors, including his or her specific life circumstances at the time. That said, common brain circuits seem to be activated during a drinking binge.

Neuroscientific research published this week offers valuable new clues on the brain mechanics that can drive people to overindulge in alcohol. The best news of this study is that the researchers discovered that turning off a circuit between two brain regions might reduce instances of binge drinking.

The April 2016 study, “Extended Amygdala to Ventral Tegmental Area Corticotropin-Releasing Factor Circuit Controls Binge Ethanol Intake,” was published in Biological Psychiatry.

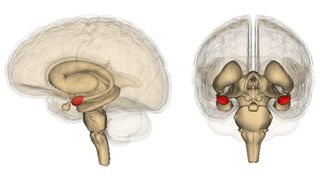

For this study, researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill honed in on two brain areas—the extended amygdala and the ventral tegmental area (VTA)—which have been implicated in alcohol binge drinking in the past. However, this is the first time that the two areas have been identified as a functional circuit.

The amygdala has long been associated with psychological stress and anxiety. The VTA is a pleasure center that responds to the rewarding properties of natural reinforcers, such as food, but also to the addictive properties of drugs and alcohol. The UNC researchers found that these areas are connected by long projection neurons that produce a substance called corticotropin releasing factor (CRF).

The study also provides the first direct evidence in mice that inhibiting a circuit between two brain regions protects against binge alcohol drinking. In a statement, lead author Todd Thiele, said,

"The puzzle is starting to come together, and is telling us more than we ever knew about before. We now know that two brain regions that modulate stress and reward are part of a functional circuit that controls binge drinking and adds to the idea that manipulating the CRF system is an avenue for treating it."

Thiele and his colleagues found that alcohol activates the CRF neurons in the extended amygdala, which directly act on the ventral tegmental area. These observations in mice suggest that when someone drinks alcohol, CRF neurons become active in the extended amygdala and act on the ventral tegmental area to promote continued and excessive drinking, culminating in a binge.

Thiele said these findings may shed light on future pharmacological treatments that may help individuals curb binge drinking and may also help prevent individuals from transitioning to alcohol dependence.

"It's very important that we continue to try to identify alternative targets for treating alcohol use disorders," Thiele said. "If you can stop somebody from binge drinking, you might prevent them from ultimately becoming alcoholics. We know that people who binge drink, especially in their teenage years, are much more likely to become alcoholic-dependent later in life."

There Are Different Types of Alcoholism

As an athlete, who has struggled with binge drinking over the years, I can identify with Michael Phelps' candid response, 'I don’t know if I’m an alcoholic.' If someone asked me, “Are you an alcoholic?" I’d respond exactly the same way as Phelps, and here’s why.

First of all, I hate labels. Second, a doctoral dissertation released this week, “Post-Mortem Brains of Alcoholics: Changes in the Glutamatergic, Serotonergic, Endocannabinoid and Neuroactive Steroid System,” by a neuroscientist in Finland, identified differences in the brain tissue of ‘anxiety-prone’ type 1 alcoholics or ‘impulsive’ type 2 alcoholics.

According to this dissertation, type 1 alcoholics typically develop alcohol dependence later in life, and they are prone to anxiety. Type 2 alcoholics, on the other hand, tend to develop alcohol dependence at a young age and they are characterized by antisocial behavior and impulsiveness. These are simple generalizations based on Cloninger's typology of alcohol abuse.

The Finnish study found that in type 1 alcoholics, changes were seen in the endocannabinoid system, which modulates stress responses, among other things. Also for type 1 alcoholics, docosahexaenoyl ethanolamide levels were increased in the amygdala, possibly because of their anxiety-prone nature.

However, the brain samples of impulsive, type 2 alcoholics showed increased levels of AMPA receptors in the anterior cingulate cortex. AMPA receptors modify the function of synapses between neurons and play a role in the learning and regulation of behavioral models. This might help to explain the impulsive nature of type 2 alcoholics.

In a statement, Olli Kärkkäinen, who presented the results in his doctoral thesis, said

"These findings enhance our understanding of changes in the brain that make people prone to alcoholism and that are caused by long-term use. Such information is useful for developing new drug therapies for alcoholism, and for targeting existing treatments at patients who will benefit the most."

It seems to me, that based on this criteria, someone could carry a genetic trait that made him or her vulnerable to alcoholism at various stages of life, but never pick up a drink in his or her life. Would that make this person an 'alcoholic' nonetheless? As Phelps wisely alluded, he's had moments where he went off the 'deep end'... but if the environmental factors don't arise again in the future, should he still be labeled an ‘alcoholic' for perpetuity? I'm not sure.

Conclusions: My Personal Experiences With Binge Drinking Over the Years

I have a hunch that as researchers dig deeper into the brain science of ‘alcoholism’ that they will discover a vast range of nuances that drive how, when, and why different people drink too much. As an example, my attraction to binge drinking isn't driven by negatives such as anxiety or impulsivity but more by the desire to 'stand outside myself' in an ego-less and transcendent way that feels ecstatic and 'otherworldly.'

In the future, you might hear someone say, "I carry the 'ABC' gene for alcoholism, but because I learned how to cope with adversity and stress young in life, it never lead to alcohol abuse." Or someone older could say, "although I haven’t had a drinking problem in the past, because I carry the 'XYZ' gene, if I face stressful or anxious situations in life, I have to be very cognizant of my brain's built-in propensity to abuse alcohol."

Along these lines, as a teenager at boarding school, my friends and I would binge drink every weekend. It seemed fun at the time. However, as I became increasingly isolated and depressed, I began drinking by myself every day which snowballed into a downward spiral of dysphoria that pushed me to the brink of suicide. Luckily, at the age of seventeen, I started running and completely stopped doing drugs or drinking alcohol. But, in many ways, the ‘runner’s high’ became a substitute for my alcohol and drug abuse.

By the time I began competing in ultra-endurance sports, I'd get so high that I would start hallucinating as if I was tripping on LSD or psilocybin during races. I also tapped into a state of what I call superfluidity during ultra-marathons in which I seemed to leave the 3-dimensions of the work-a-day world and enter a mystical and blissed-out state of consciousness marked by zero friction, zero viscosity, and zero entropy. Superfluidity is a term I borrowed from the world of quantum physics to describe the highest tier of what Mihály Csíkszentmihályi identified as flow.

Unfortunately, when I retired from sports—and could no longer experience this type of ecstasy endogenously—alcohol and binge drinking became very seductive again because it took me to that enchanted dimension of 'standing outside myself.' I’m sure this happens to a lot of retired athletes. Much like superstars in the entertainment world who get hooked on drugs and self-destruct in an attempt to stay in some type of vortex; I can easily see myself abusing alcohol in my quest for superfluidity, especially with my history of teenage drinking.

Although 12-step programs have helped millions of people get, and stay, sober, I would never stand up in an AA meeting and say “Hi. My name is Christopher, and I’m an alcoholic.” Not because I’m ashamed of the fact that I’ve often consumed way too much alcohol and have been totally out of control with binge drinking at times in my life (much like Michael Phelps) but more because I don’t think it’s an accurate description of the multifaceted and complex person I am.

There is an important caveat. The pragmatic empiricist in me looks at my own relationship with alcohol very objectively. As with many things in my life, when it comes to binge drinking, I consider myself somewhat of a human lab rat in my own neuroscientific experiment. I have no delusions. I know I'm a sitting duck for addiction. That is why I will always proceed with extreme caution when it comes to consuming any mind-altering substances and avoid drugs at all costs.

Lastly, because I have no desire to sabotage my life—and I know that binge drinking is my Achilles' heel—I choose to avoid drinking alcohol these days. That said, if anyone asks me if I’m an alcoholic in the future, I’m going to borrow Phelps’ line, and say, “I don’t know. I honestly don’t know." Thank you Michael Phelps for being such an inspiration and role model on so many levels!

To read more on this topic, check out my Psychology Today blog post,

- "Michael Phelps and the Romance of Heroic Journeys"

- "The Dark Side of Mythic Quests and the Spirit of Adventure"

- "Why Do So Many Superstars Self-Destruct Like Supernovas?"

- "Superfluidity: Decoding the Enigma of Cognitive Flexibility"

- "The Psychological Damage of Alcohol Can Be Lethal"

- "What Are the 11 Symptoms of "Alcohol Use Disorder"?"

- "Hyperactive Dopamine Response Linked to Alcoholism"

© 2016 Christopher Bergland. All rights reserved.

Follow me on Twitter @ckbergland for updates on The Athlete’s Way blog posts.

The Athlete’s Way ® is a registered trademark of Christopher Bergland