Memory

How Does Body Posture Affect Early Learning and Memory?

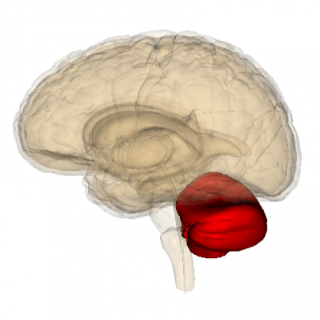

The cerebellum may help integrate bodily posture with cognitive development.

Posted March 19, 2015

A fascinating new study from Indiana University (IU) has combined state-of-the-art robotics with research on human infants to reveal that posture plays a critical role in the early stages of acquiring new knowledge.

For infants, one of the first obstacles for learning a new word is to map the word with its physical reference. The second problem is how to recall the mapping of the new word and the referent object when they are encountered again. Recent infant studies have found that spatial location plays a key role in how infants overcome both of these obstacles.

The new study uses a variety of name-object mapping tasks. In addition to working with infants, a humanoid robot model was used to test the hypothesis that body-centric spatial location—and the bodies’ momentary posture—play an integral role in binding the characteristic features of auditory names with visual objects.

The March 2015 study, “Posture Affects How Robots and Infants Map Words to Objects,” was published yesterday in the PLOS ONE online journal.

This interdisciplinary study was led by Linda Smith, a professor in the IU Bloomington College of Arts and Sciences' Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences. Anthony Morse, a senior post-doctoral research fellow in the Centre for Robotics and Neural Systems at the University of Plymouth, and Viridiana Benitez, a post-doctoral research associate at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, collaborated with Smith on this research.

For years, Smith's research has been dedicated to creating a framework for understanding cognition that differs from the conventional approach. Traditionally, cognitive research separates physical actions such as using tools or riding a bicycle from cognitive actions such as learning language or playing a game of chess. Smith elegantly brings "implicit' and "explicit" learning together in her research.

In this study, the researchers used both robots and infants to examine if bodily position and posture plays a role in the brain's ability to "map" names to objects. They found that the bodily posture of both robots and infants was key to successfully connecting the name of the object with the object itself when being taught a new object's name. Here is a YouTube video that shows how Anthony Morse teaches the robot “iCub” the name of a new object.

The ITALK project is working to develop robots that are able to acquire complex behavioral, cognitive, and linguistic skills through individual and social learning. The research the roboticists at ITALK are doing with the iCub humanoid robot could lead to the development of a sentient robot someday.

iCub is being taught how-to: handle and manipulate objects and tools, to cooperate and communicate with other robots and humans, and to adapt to changing internal, environmental, and social conditions.

Is Art Imitating Life When It Comes to Artificial Intelligence, or Vice Versa?

Last night, I went to see the movie Chappie which is about a sentient robot that is born with a tabula rasa of consciousness and must go through the traditional Piaget stages of sensorimotor development to acquire new knowledge and mature into an adult.

Although Chappie isn’t a masterpiece, it does raise complex moral and ethical questions about a burgeoning field called epigenetic robotics. Artificial intelligence researchers working in epigenetic robotics are striving to create humanoid robots that learn and develop like children through autonomous interactions with their environment.

Last week, I wrote a Psychology Today blog post about neuroscientific advances in the field of robotics titled, "The Cerebellum Holds Many Clues for Creating Humanoid Robots."

Could the Cerebellum Be Playing a Role in Both Posture and Object-Mapping?

The cerebellum has a wide range of responsibilites that include the maintenance of balance, posture, proprioception and integrates all of these to fine-tune and coordinate muscle movements. Traditionally, neuroscientists haven't considered the cerebellum to play a role in cognitive function or learning and memory. This viewpoint is changing.

Earlier this week, NPRs “Morning Edition” and “All Things Considered” broadcast reports on the cerebellum based on the research of Jeremy Schmahmann at Harvard Medical School. Schmahmann has a theory that just as the cerebellum fine-tunes motor movements, it also fine-tunes cognitive function.

Recently, I wrote a Psychology Today blog post about Schmahmann's research at Massachusetts General Hospital titled, "The Cerebellum Deeply Influences Our Thoughts and Emotions."

Although the researchers at UI aren’t focusing on the cerebellum, it seems logical to me that because their findings hinge on body posture and proprioception (which are both under the control of the cerebellum) that there may be a cerebellar link to their research that dovetails with Schmahmann’s research.

People with cerebellar disorders often have difficulty shifting their posture forward or backward without losing their balance. Based on these new findings one might ask: What are the cognitive impacts of cerebellar disorders on learning and the ability to map names with objects in the early stages of childhood development?

Robotics, Neuroscience, and Cognitive Science Are Increasingly Intertwined

Increasingly, there seems to be a feedback loop between new information gained about human cognitive function coming from the resources being directed to the development of learning robots and vice versa.

This new study marries the two in an unprecedented fashion. Morse applied Smith's earlier research which focused on creating a learning robot in which cognitive processes would emerge from the physical constraints and capacities of its body.

In a press release Smith said, "This study shows that the body plays a role in early object name learning, and how toddlers use the body's position in space to connect ideas. The creation of a robot model for infant learning has far-reaching implications for how the brains of young people work."

Smith added, "A number of studies suggest that memory is tightly tied to the location of an object. None, however, have shown that bodily position plays a role or that, if you shift your body, you could forget."

Conclusion: Posture and Cognitive Development Appear to Be Symbiotic

"These experiments may provide a new way to investigate the way cognition is connected to the body, as well as new evidence that mental entities, such as thoughts, words and representations of objects, which seem to have no spatial or bodily components, first take shape through spatial relationship of the body within the surrounding world," Smith concluded.

Additional research is needed to determine whether the results of this study apply only to infants and toddlers. Future research could lead to the development of treatments and interventions for a wide range of developmental disorders in which motor coordination and cognitive development are causing any type of "dysmetria."

© Christopher Bergland 2015. All rights reserved.

Follow me on Twitter @ckbergland for updates on The Athlete’s Way blog posts.

The Athlete’s Way ® is a registered trademark of Christopher Bergland.