Intelligence

Are You Too Smart to Think Wisely?

Brain power can contribute to surprising reasoning mistakes.

Posted March 6, 2019

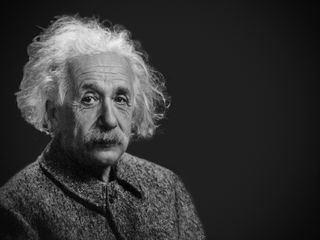

What do Albert Einstein, Arthur Conan Doyle and Thomas Edison have in common? All of them were ground-breaking geniuses, of course! Einstein spearheaded modern physics, Conan Doyle created brilliant fiction, and Edison developed the light bulb as well as 2,331 (!) other patented inventions. However, their astronomical IQ isn’t the only similarity. Despite their incontestable intelligence, all three of them held seriously misguided beliefs about major aspects of life. Einstein was a firm believer in socialism and refused to recognise the failure of the Soviet Union. Conan Doyle believed in fairies and thought his own wife could talk to spirits. Finally, Edison fought a pointless battle for the introduction of direct currents (as opposed to alternating currents) for the transmission of electricity. While personally I have no clue what this means, I’ve been assured that his beliefs were seriously misguided for a man of his knowledge, and that it demonstrated an embarrassing reasoning failure.

If Einstein, Conan Doyle and Edison were so very clever, how could they possibly hold such mistaken beliefs? In his brand-new book “The Intelligence Trap”, science journalist David Robson investigates exactly this question, and he comes to several surprising conclusions. It seems like a high IQ alone is not predictive of wise decision making and overall life success. In fact, brain power may often contribute to severe reasoning mistakes, and here is why:

Multi-faceted intelligence

One of the main problems with the concept of intelligence is its traditionally narrow definition. IQ tests only measure analytic skills and the speed with which we solve verbal or numerical problems. However, an increasing number of scientists suggest that things aren’t quite so simple. Perhaps analytic intelligence is only one dimension of intelligence, which does not reflect the entire breadth of skills required for successful decision making? Robert Sternberg, for example, proposed two additional dimensions, both of which appear intuitively important for wise choices. The first is practical intelligence, which describes pragmatic life skills such as the ability to plan a multi-legged journey, and the second is creative intelligence, which refers to the ability to think outside the box and imagine alternative solutions.

Over-confidence and bias blind spot

In addition to limitations of a one-dimensional type of intelligence, people with high IQ frequently show over-confidence. Based on past life experiences, so-called geniuses often over-estimate their own abilities, with a tendency to stubbornly believe they’re always right. Similarly, highly intelligent people may suffer from a “bias blind spot”. This term refers to the inability to recognise own unconscious biases during decision making, which occur independently of analytic intelligence. People within the normal IQ range expect to make mistakes, doubt their own judgments and are therefore more sensitive to biases. Above-average geniuses, on the other hand, frequently fail to consider the possibility of errors, thereby leaving them particularly vulnerable to common biases.

A particularly powerful bias affecting intelligent people is the confirmation bias (also called myside-bias), which can be described as a tendency for motivated reasoning. More specifically, it involves seeking supportive arguments for their own opinion and neglecting any criticism or counter-evidence. By applying their intelligence in a one-sided, biased manner to justify own ideas and theories, a genius’ analytic skills can therefore serve to perpetuate mistakes.

Intuitive judgements

Motivated reasoning is particularly troublesome, when intelligent people investigate a mere hunch or intuitive view. In many cases, such intuitive judgements can be surprisingly accurate. This is because many clever people have expert knowledge in their fields of interest, and expert knowledge is usually associated with automatic, gist-based reasoning and a more holistic understanding of the topic. Hence, experts tend to focus on the bigger picture, rather than carefully analysing minute details, and this allows them to make faster and better judgements. Despite high accuracy rates, however, experts’ intuitive judgements are never infallible. And it is in those cases that cognitive biases might hit them the hardest.

A simple analogy

The cognitive pitfalls outlined above might constitute a dangerous “intelligence trap” for the super smart, and this can be illustrated with a simple analogy. Let’s think of the human brain as a car engine, with high IQ equating to engine power. While cars with powerful engines inevitably drive quicker than others, they don’t necessarily end up in the right place. Obviously, their destination will depend just as much on steering than on speed. For example, driving the latest Ferrari might help you overtake the neighbour’s old VW Beatle, but it is unlikely to prevent you from getting stuck in a dead-end, from going round in endless circles, or from shooting off a cliff. Similarly, a quick-wired brain might help you process information faster and find a quicker solution. However, if the direction of your reasoning is influenced by dangerous biases, your errors are likely to be only aggravated by your speed of thinking.

Have you ever noticed yourself getting caught in the intelligence trap? I certainly have! Not only am I tragically inept when it comes to operating new washing machines or TVs (or any electric appliance, really), I also keep falling for the ever-multiplying health and beauty myths spread by women’s magazines all over the world. Note to myself: If you come across a face cream that’s supposed to remove spots and wrinkles while giving you a natural-looking tan and making your nose look smaller, it’s probably a scam!

So how can you avoid foolish mistakes fueled by your own intelligence? Open-mindedness, continuous self-questioning and a willingness to change one’s mind (all of which happen to be principles of the yogic understanding of wisdom) are key factors for making wiser choices. For hands-on advice—have you ever talked about yourself in the third person?—see Robson’s delightfully informative monograph, or wait for my follow-up post.