Fear

Using the Mind as a Blanket

Exploring the remarkable physiology of "The Iceman."

Posted October 12, 2022 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- There is compelling evidence that the human brain can control body temperature.

- Wim Hof, also known as "The Iceman," is a real-life example.

- A simple breathing technique may help people achieve brain-over-body focus.

The mind has incredible powers—it can create illusions out of thin air and hear voices that don’t exist. It can modify the body’s response to pain, disease, and stress. It can eliminate symptoms simply through the power of belief.

The mind is powerful, but is it capable of regulating body temperature? Wim Hof of the Netherlands, known to some as “The Iceman,” would have us believe that it is.

Wim Hof is 63 years old and has flat and thinning hair and shorts that ride higher than warranted. He looks rather ordinary, but unlike most other humans on the planet, he can seemingly mute his body’s response to extremely cold temperatures.

His feats are remarkable. The Iceman, whose stated profession is “world record breaker,” has completed each of the following cold tricks: 1) stood fully immersed in 700 pounds of ice for one hour and 44 minutes, 2) hiked to the top of Mount Kilimanjaro (19,340 feet) in two days wearing only shorts, and 3) completed a full marathon in similar attire in temperatures averaging about -4 degrees Fahrenheit.

We can all safely agree that these feats are not for the average weekend warrior and may be unnecessarily masochistic. But Wim apparently finds them therapeutic. “Cold is a warm friend,” he has said.

And yes, cold is nice—in ice cream and popsicles—but how does someone stay submerged in ice for almost two hours without damage? Scientists who have studied Wim’s response to cold temperatures are amazed. Incredibly, Wim can maintain a stable core body temperature for nearly an hour while submerged in ice—a trick that you would absolutely not want to try at home. And his heart rate and breathing also stay stable—once again, not the expected response.

So, something about the Iceman is different. Perhaps it is his lifetime of acclimatization to cold temperatures, or maybe he is a genetic freak. Or maybe, just maybe, it is because he is an alien—because humans aren’t supposed to be able to do this sort of thing. So say the experts.

“In general, extreme abilities to withstand cold exposure rarely emerge within the lifespan of individuals as thermoregulatory mechanisms are largely autonomous and not subject to willful and/or tonic modification.” [Muzik]

Over a decade ago, when I first heard about Wim, this is where the explanation landed: He isn’t supposed to be able to do this, but somehow he does.

I was recently motivated to investigate the research around Wim because, in 2022, the Iceman has been accumulating publicity like frost on the tundra. You may have heard of his new BBC program Freeze the Fear or read his Q&A in The Guardian or his long-form profile in Men’s Health. I also discovered a fascinating study by Otto Muzik and colleagues, who were so intrigued by Wim’s outlier abilities that they designed a neuroimaging study around him.

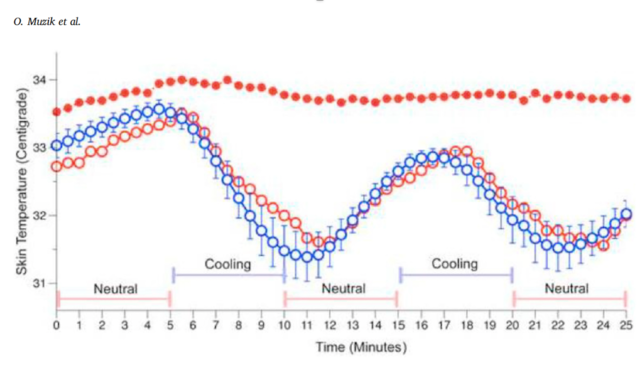

Here is what they did: They employed several different modalities (including functional MRI and PET scanning) to compare Wim to other normothermic individuals under a series of distinct cold-stress conditions. Here is one example of what they found.

You see the three dotted lines depicting changes in skin temperature of control study subjects (blue) and Wim (red) when exposed to a skin suit infused with either neutral (31-34 degrees C) or cold water (15-17 degrees C). The open red circles represent the Clark Kent version of Wim (when he isn’t engaging his breathing superpowers), and the solid red is SuperWim (when he is). Super Wim Hof has no appreciable change in skin temperature, even when exposed to very cold water. These findings were borne out in their other experiments, demonstrating that Wim is able to activate areas of his brain when exposed to cold that others are not.

The Secret to Super Wim

He calls it the Wim Hof method (WHM), and it is based on the principles of Tummo meditation, an ancient practice of Buddhist Monks. Thirty years ago, a study by Herbert Benson and colleagues reported the bodily responses of Indo-Tibetan Yogis practicing this technique—demonstrating remarkable changes in the temperature of their fingers and toes (up to 17 degrees Fahrenheit) in a cold environment. Later, the same team produced videos of Tibetan monks drying frigid, wet sheets with their own body heat [Cromie].

So, it seems possible to alter the brain’s automatic nervous system (ANS) merely through the focus of the mind. We do know that it is not unprecedented in the animal kingdom: Many animals, including snails and bees, can regulate body temperature. Specifically, WHM consists of a daily practice of, at a minimum, three elements: a) several rounds of forced hyperventilation followed by breath retention and deep breaths in and out, b) exposure to cold (e.g., immersion in ice-cold water), and c) mindful body awareness focus on deep breathing [Muzik, Kox].

As it turns out, Hof’s Freeze the Fear series is all about trying to teach WHM to celebrities and help them overcome physical challenges. The results are mixed—not everyone is up to the ice water immersion test—and the production itself was a bit of a flop with critics.

While it may be that the Iceman is currently in a state of overexposure to the ambient media, this doesn’t negate his remarkable physiologic achievements nor the implications for the rest of us that we are barely scratching the surface of our own WHM-like potential. It is a wonderful irony that, for many of us, what often limits the power of the mind is its preference for the status quo. You might say that the greatest impediment to the mind is the mind itself.

References

Muzik O, Reilly KT, Diwadkar VA. “Brain over body”–A study on the willful regulation of autonomic function during cold exposure. NeuroImage. 2018 May 15;172:632-41.

Cromie WJ. Meditation changes temperatures. Harvard Gazette. 2002 Apr 18:1-5.

Kox M, van Eijk LT, Zwaag J, van den Wildenberg J, Sweep FC, van der Hoeven JG, Pickkers P. Voluntary activation of the sympathetic nervous system and attenuation of the innate immune response in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014 May 20;111(20):7379-84.