Marriage

Living Together Before Marriage May Raise Risk of Divorce

Is living together before marriage associated with risk in marriage or not?

Posted November 3, 2018 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

by Scott M. Stanley and Galena K. Rhoades

One of the most perplexing findings in the history of the study of marriage is that living together beforehand is associated with greater, not lesser, odds of struggling in marriage. This association had been clear in study after study up to around 2007, and then a number of studies and social scientists declared that the association between living together before marriage and difficulties in marriage had disappeared.

To be clear, we never thought the association had disappeared. While we believe the association got weaker, we have long believed that the understanding of it mostly became better understood. For example, we predicted and found — repeatedly, and in numerous samples — that an important part of the story had to do with whether or not a couple started living together before or after having come to a clear commitment to marry. Those who cohabited only after engagement (or marriage, of course) have an edge in odds for doing well in marriage compared to those who started living together before clarifying the big question about the future. We will explain that more below.

Among some scholars in family science, the belief had been settled that there simply is no risk for worse outcomes in marriage associated with living together beforehand. Well, that no-risk story just received a jolt. A new study published in the Journal of Marriage and Family finds that the “premarital cohabitation effect” lives on, despite earlier claims to the contrary. The premarital cohabitation effect is what this is all about: the finding (over many studies, over decades of time) that those who live together prior to marriage are more likely, not less, to struggle in marriage. Here, we are going to take you through a fairly deep dive into what the hubbub is all about.

The new study is by Michael Rosenfeld and Katharina Roesler. Their findings suggest that there remains an increased risk for divorce for those living together prior to marriage and that prior studies suggesting the effect went away had a bias toward analyzing shorter versus longer-term effects. They found that living together before marriage was associated with lower odds of divorce in the first year of marriage, but increased odds of divorce in all other years tested, and this finding held across decades of data.

Numerous Recent Studies Reported No Impact of Premarital Cohabitation

A number of relatively recent studies suggested that the premarital cohabitation effect had gone away for those marrying in the past 10 or 15 years. Rosenfeld and Roesler pay particular attention to a report from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) by Copen, Daniels, Vespa, and Mosher in 2012, which suggested there was no increased risk associated with premarital cohabitation in the most recent (at the time) cohort of the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG; 2006-2010). The NSFG is a large, ongoing sampling of those living in the U.S. with regard to many aspects of family formation, cohabitation, and marriage. Other researchers, such as Manning and Cohen, reached the same conclusion as the authors of the NCHS in 2012, incorporating data from as late as the 2006 to 2008 cohort of the NSFG.[i]

While all of these studies used the same large sampling effort, Rosenfeld and Roesler had longer-term data for the most recent cohort they studied (up to 2015). Contrary to these prior conclusions, they found that there remains a clear link between premarital cohabitation and increased odds of divorce regardless of the year or cohort studied. (In all these studies, the focus is on first marriages.)

Many experts believed that the cohabitation effect, well understood since the 1980s, would go away as living together became more the thing to do — that it would no longer be associated with negative outcomes in marriage. This hypothesis is based on the idea that the prior stigma among friends and family about living together before marriage was a cause of the increased risk. And, clearly, there is not much, if any, stigma now. (We wrote about trends in cohabitation in the U.S. in great detail here earlier this year.) The other reason for expecting the cohabitation effect to go away is a little more arcane, having to do with the fact that as it became common (at least 70 percent of couples live together before marriage now), those who chose to do so are no longer more select for being at greater risk than others.

Based on a different line of reasoning than the other studies suggesting no risk, another prominent study had also concluded that there was no longer an added risk for divorce associated with premarital cohabitation. However, in that study, Kuperberg (2014) concluded the risk was more about moving in together at a young age (before the middle 20s) than moving in together before marriage, per se. That’s one among many potentially important nuances in this complex literature.[ii]

Pumping the Brakes on the Conclusions of No Added Risk

Cohabitation is the gift that keeps on giving to family science, providing generations of scholars with the opportunity to say, “Look here, wow, this is strange.” And people remain interested. We have seen major stories on cohabitation break across the media for over 20 years because it’s interesting. In fact, here is a recent story in The Atlantic about this very thing, and it includes numerous quotes from the second author here, Galena Rhoades, based on our work. We think this subject keeps getting lots of ink because the findings have tended to be so counterintuitive. Most people believe that living together before marriage should improve the odds of doing well in marriage. However, whatever else is true, there is very scant evidence to support this belief in a positive effect (more on that can be found in this piece).

By the way, we’re not trying to change your views of whether or not a couple should live together before marriage. Our own views are complex and nuanced. However, we may convince you that there is something to learn from the research that bears on what pathways may be wiser than others for the average person. So, let’s get back to the new study that is getting a lot of buzz.

Rosenfeld and Roesler’s study is quite complex statistically, but their insight boils down to two things easily explained. First, they believe studies that suggested that the premarital cohabitation effect has disappeared simply did not have outcomes for divorce far enough out for those who had married in the recent cohorts that they examined. Second, they show that premarital cohabitation is associated with a lower risk for divorce, but only very early in marriage (in the first year); in contrast, the finding flips, with premarital cohabitation being associated with higher risks for divorce in years after that first year. That’s what earlier studies could not address.

In particular, Rosenfeld and Roesler suggest that those who live together before marriage have an advantage in the first year because they are already used to all the changes that come with living together. Those who go straight into marriage without living together have a bigger immediate shock to negotiate after marriage, and as a result, have a short-term increased risk that’s greater than those already living together. But that’s the short term, and the risk remains long term.

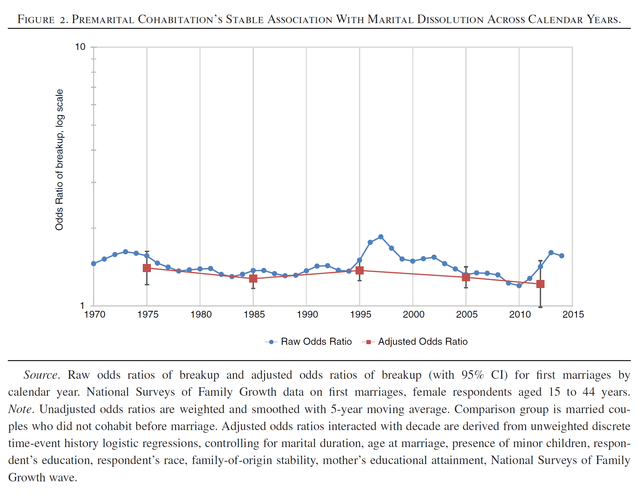

Here is a quote from the new paper (Figure 2 below is included here with permission):

Figure 2 shows that, for the years in which the NSFG has substantial numbers of marriages and breakups, there was no apparent trend over time in the raw or adjusted odds ratios of breakup for premarital cohabitation. Given the enormous changes over time in the prevalence of premarital cohabitation (see Figure 1), Figure 2 shows a surprising stability in the association between premarital cohabitation and marital dissolution over time. (Pgs 7-8)

Theories of Increased Risk

There are three main theories for how living together before marriage could be causally associated with worse outcomes (on average) in marriage. Rosenfeld and Roesler address the first two but did not say anything about the third.[iii]

1. Selection — This theory is simply that there are many factors associated with who cohabits when and why, and with whom, and that those factors are also associated with how marriages will turn out regardless of cohabiting experience. For example, it’s well known that those who are more economically disadvantaged are more likely: to live together outside of marriage, to live together with more than one partner, to have a child with a cohabiting partner prior to marrying, and to struggle in marriage. Other factors are religiousness, traditionality, and family history (parental divorce, etc.). The selection explanation is that those who cohabit in riskier ways (e.g., before marriage, before engagement, with more than one partner) were already at greater risk. In the strongest view of selection, living together does not add to the risk at all, because it’s all already baked in. There is a lot of evidence for selection playing an important role in this literature, and scholars in this area note this and address it in various ways.

2. The Experience of Cohabiting Changes Things — In an older line of research that was clever, but needs to be tested again with those marrying in more recent years, Axinn and Barber (1997) showed that cohabiting changes attitudes about marriage and divorce, lowering esteem for marriage and increasing acceptance of divorce. This is consistent with scores of studies in psychology showing that attitudes will cohere to behavior. In other words, you will bring your beliefs around to fit your behavior. Earlier, Thornton, Axinn, and Hill (1992) showed that cohabiting led to people becoming less religious. Rosenfeld and Roesler included a lot on the theory of experience but mostly use it to emphasize the short-term benefit of already experiencing living together when transitioning into marriage.

3. Inertia — We have argued since the early 2000s for another causal theory in this line of research. Drawing on theories of commitment, we suggested that what nearly everyone misses in understanding the risk associated with cohabitation is pretty simple: Moving in together makes it harder to break up, net of everything else. The added risk is due to how cohabitation substantially increases constraints to remain together prior to a dedication to a future together maturing between two partners. Two key papers on this perspective are here and here.[iv]

One primary prediction from the inertia hypothesis is that those who only started living together after being already committed to marriage (e.g., by engagement or actual marriage) should, on average, do better in marriage than those who may have prematurely made it harder to break up by living together before agreeing on marriage. The inertia hypothesis completely embraces selection, suggesting that relationships already at greater risk become harder to exit because of cohabitation. Various predictions from the inertia hypothesis have been supported in ten or more studies, seven of which include tests of the prediction about pre-cohabitation level of commitment to marriage (aka plans for marriage prior to living together) — and this latter finding exists in at least six different samples across a range of outcomes.[v]

There is no particular reason to expect that the inertia risk will dissipate with increased acceptance of cohabitation, because the mechanism is about the timing of the development of aspects of commitment, not about societal views and personal attitudes. For living together to lower risk in marriage, the benefit of learning something disqualifying about a partner has to exceed the costs of making it harder to break up that come with sharing a single address. Hence, inertia is another possibility, along with experience, that could explain the persistence of a cohabitation effect, such as that found by Rosenfeld and Roesler.[vi]

Other Possibilities — Other factors that may be associated with differential outcomes include pacing (Sassler et al.), age at the time of moving in together (Kuperberg), and having children before marriage (Tach & Halpern-Meekin). All such theories suggest that the risks of living together before marriage are greater for some people than others. Rosenfeld and Roesler are not really addressing this issue. However, they did find that the risks associated with premarital cohabitation were lower for African Americans. While that’s a subject far beyond our focus here, it does not surprise us. For most groups, cohabitation is no particular indicator of higher commitment. However, it may well signal higher levels of commitment among groups where marriage has declined a great deal, like African Americans.

Rosenfeld and Roesler also note that the risks of living together before marriage were even greater among those who had lived with more than just their mate prior to marriage. That finding is consistent with many other studies: for example, Teachman (2003).

The Effect and the Controversy Lives

Research on premarital cohabitation has long been mired in arguments about causality, with the dominant view being that what we describe about selection explains most, if not all, of the added risk when found. However, many studies in the history of this field have controlled for all sorts of variables associated with selection and still found an additional risk. In fairness, it is not possible to control for all aspects of selection in such studies. Without randomly assigning people to walk different pathways before marriage, causality can never be proven. And we think it’s going to be a long time before researchers are allowed to flip a coin about who does what in their love lives so that we can study the phenomena better. Oh, how great that would be, though, for figuring things out. Since we have to live with studying what people end up doing on their own, arguments ensue. Besides, since when does evidence stop arguing anyway when people are passionate about their view on something?

Rosenfeld and Roesler’s new study breathed life into a finding many concluded was dead. Perhaps it was just mostly dead.

Scott M. Stanley and Galena K. Rhoades are research professors in the department of psychology at the University of Denver. A different version of this article appeared on the blog for the Institute of Family Studies on October 17, 2018.

References

[i] We are mystified why the new paper does not cite or address the findings by Manning and Cohen. That study seems like it is the most recent major study directly addressing the question Rosenfeld and Roesler examine.

[ii] Scott wrote about the Kuperberg study at that time, taking far more issue with the media stories about it than the actual study, suggesting there are many ways people could misconstrue to whom those, and other findings of differential risk, applied. Those articles are here and here.

[iii] This omission does not seem as striking to us as the omission of Manning and Cohen’s paper, since their paper is already complex and they are intent on addressing one moderator of the cohabitation effect: how long after marriage the effect is measured. They do not address at all the growing literature on moderators of the cohabitation effect. Still, inertia is one of the major theories of increased risk, and only selection itself has more publications addressing it.

[iv] An accessible, word document version of the major theory paper can be found here. A full run down of our theoretical and empirical work in this line is available here. That includes citations and links, mostly to accessible versions of the articles in the literature.

[v] We have found evidence for inertia whether or not someone has cohabited only with their mate, and in numerous samples of people marrying after 2000 and later.

[vi] As an interesting side point on the subject of the inertia hypothesis, the commitment to marriage/timing effect exists in the NSFG. It was mentioned in passing in a working paper leading up to the 2010 publication by Reinhold, and it is mentioned prominently in the abstract (and paper) in Manning and Cohen’s 2012 publication.