Fear

Death and the Risk-taker

Anne Dufourmantelle, who advocated taking chances, dies as she lived.

Posted August 14, 2017

(First in a two-part series)

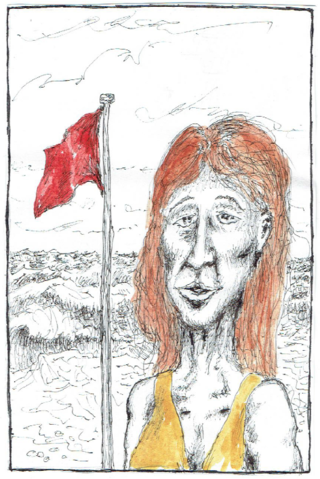

It was rough in the Mediterranean on July 21st, in the waters off Pampelonne, near the French resort of Saint Tropez. A red flag had gone up on the beach indicating bad weather, forbidding bathing. Two children who ignored or didn’t see the warnings had got into trouble in the crashing surf. A 53-year-old woman swam out to help them. The children were saved.

The woman died.

The woman was Anne Dufourmantelle, a French philosopher, psychoanalyst and writer whose 2011 book, L’Éloge du risque (In praise of risk), advocated taking risks in life, and by the same token criticized a life lived in constant fear of death or injury. Her drowning generated a wave of publicity in France, some of it focused on the apparent irony of taking chances for a better life that ended in life’s opposite. The friendlier obituaries noted that the philosopher had at least practiced what she preached.

The wave of publicity had subsided to a mere ripple by the time it reached America’s shores, perhaps because to the average American intellectual the death of yet another French philosopher was hardly worthy of comment.

I suspect, however, that there was another reason, and it had to do with the fact that America is a world capital of the fear-ridden life. In this country we are so obsessed with keeping ourselves safe that any voice raised against that obsession is simply drowned in the overriding clamor of our mania for risk-free existence.

Here is some anecdotal evidence that can be corroborated by anyone who grew up in middle-class America in the sixties. In those days children rode bikes without the protection of helmets or anything else, walked to school sans adult supervision, played with friends in suburban streets all evening during which time they stayed completely out of touch with their parents. In those days a parent could leave an infant in its stroller for a few minutes outside while buying milk in the corner grocery store, and no one would notice, let alone object.

Today virtually no middle-class American parents would permit any of this, and if they did they might well get into trouble. Five-year-olds now wear helmets and elbow- and knee-pads just to ride three-wheeled scooters; eight-year-olds are ferried to and from the school gates in convoys of SUVs; teens carry cellphones with which they are expected to communicate with parents at all times—that is, when the phones are not hooked into a GPS network that continually flags their position on the hovering adult’s device.

In New York City a few years ago, a Danish woman was actually arrested for leaving her child in a stroller outside a restaurant, a practice common in her native country.

Of course there is nothing wrong with wanting to protect one’s child from harm; quite the contrary. Although conscious of the issue when my children started to ride bikes, I could not stomach taking risks with my kids’ safety for the sake of my airy philosophical principles; I bought them helmets as well, I shepherded them to school till they were teens.

And of course it's normal for anyone to wish to avoid danger and death.

But a problem arises when the fear is irrational, a function of fads and vague rumor. For example, the fear of child abduction; actual kidnapping of children is no more prevalent now than it was in the sixties. By some counts, it’s on the decline.

And there is a problem when the fear of risk, as Anne Dufourmantelle wrote, starts to negatively affect one’s life. “To live fully is a risk,” she said in an interview with the French daily Libération. “Very few people live fully. There are many zombies, the living dead, lives diminished by ‘the sickness of death,’ as Kierkegaard called it.”

Dufourmantelle was interviewed at a time when France was reeling from two major terrorist attacks. A point she didn’t make in the article was this: while entire countries, the U.S. included, obsess over the risk of terrorism, the statistical chance of an American being killed in a terror attack is less than that of being crushed to death by a television or falling furniture, or of being killed by a toddler. It is five times less than being struck by lightning. How many of us obsess over plummeting TVs, or murder-by-two-year-old, or even lightning?

And yet, as a culture, we are terrified by “terrorism.” We expect to be totally protected at all times, at all levels. We want our health technology to be the best in the world because, on some level, we think it might prevent us from dying, at least in the immediate. Over 17 percent of our GDP is devoted to healthcare alone; that percentage is growing fast and is expected to top 20 percent by 2020, even though experts know that the most effective tool for extending life expectancy is very basic prevention made generally available.

One study reckoned that over half our GDP is spent, in one form or another—military spending, security and safety services, health—in activities meant to deny the possibility of sickness and death for Americans. Vast sectors of our economy are profitably invested in selling the myths and technologies of risk-denial.

A certain, very American, sanctimoniousness is attached to the subject. When I ride bikes or go skiing without a helmet: because I know the risks, because I like the freedom of riding or skiing unprotected, because my kids are pretty much grown now and could survive my disappearing; normally rational friends have been known to criticize me harshly, as if I had violated some moral code.

I wrote in a recent book that, to gain insight into Arctic navigation, I had gone kayaking in winter, through ice-bound New England waters. The book garnered generally enthusiastic reviews but one critic excoriated the entire effort on the grounds that I had not worn a lifejacket.

A more serious point made by Dufourmantelle’s work is this: the obsession with risk-avoidance can easily facilitate, in their regulatory form, the instruments of political control.

“You have to beware of anyone who offers you total security, because this sheltering function often works in perverse ways,” she told Libération. “Security legislation provokes transgressions that in themselves justify new security regulations, it’s a vicious circle. ... To truly protect people is to be assured of their ability (or inability) to experience their freedom. To live, by definition, is to take risks. A free being is harder to influence than one who is governed by fear.”

It's almost as if she knew about the Patriot Act.

Next: Developmental Downsides of Safety Mania