Behaviorism

Are There Any Geniuses in the Field of Psychology?

Can behavioral science hold a candle to computer science?

Posted August 9, 2016

I was recently awed by reading Walter Isaacson's book about the nerds and geniuses who brought us the digital revolution (see: "The most inspiring book I've read"). But besides feeling awe, though, I also felt a bit envious. I asked myself: Does psychology have any geniuses comparable to Alan Turing, Steve Jobs, or Jack Kilby (who won a Nobel prize for his part in inventing the silicon chip)?

The field of psychology has certainly attracted its share of people with high IQs. But have all those brilliant psychologists created any behavioral technologies to rival the digital technologies created by computer scientists?

Before sharing my ruminations on this question, though, I’d like to ask you to stop reading for a second, and write down a name or two that comes to your own mind, along with a sentence or two about why this person deserves to be called a genius. That will help you prime your mind for what comes next (and if you feel like sharing your nominations, I’d love to hear them, so feel free to post a comment):

Can lifelong ignorance be an opportunity?

I first thought this would be an easy little task I could knock off in a few hours. Heck, I have been studying psychology for almost 50 years now, I coauthored a general psychology textbook that went through a couple of editions, and opened each chapter with a historical perspective. I have also coauthored a social psychology textbook that is in its 6th edition, and I’ve written several other psychology books. All those years of reading and learning about the field of psychology should have put me in a position to snap off a decent list in short order.

Although I did generate an initial list without too much trouble, it’s been over 3 weeks and I am still working on this question. In fact, I will still probably be working on it 3 months from now. Why the delay? Well, once I sat down to really think about the question: “Who are psychology’s geniuses?” I became painfully aware of how badly I need another 40 years in the field to better educate myself. That humbling realization was amplified after I posed the same question to a half dozen of the smartest psychologists I know. Turns out, I know surprisingly little about some of the greatest thinkers in psychology, and I even have a lot to learn about the psychologists whose work I thought I was familiar with.

So, in the interest of continuing education, I have spent the last week or two digging through my old books on the history of psychology, checking out the writings of authors who made it onto my initial list or who were mentioned by my panel of expert judges, ordering several more books to add to my library, and downloading classic articles written by members of the possible genius list. This is hardly an efficient way to knock off a blog posting, but it does make me appreciate the best thing about my job as a university professor – lifelong learning is a central part of my job description.

The methods section

Blog posts are ideally short and sweet. But my recent reading has uncovered enough information to strain the attention span of the most dedicated reader of the Atlantic Monthly. So, I am going to answer the question “Who are psychology’s geniuses” in a few separate chunks:

First, I will share with you my initial off-the-cuff list, the version from before I consulted outside experts and started my reading program. This isn't the most rigorous method, but it can help make you aware of some of the limitations on how your mind works. I will also suggest a few readings for each of my nominees, in case you also want, like me, to continue your education (or simply distract yourself from getting through your to-do list).

Second, I will share with you the other nominations I heard from several of my brilliant and thoughtful colleagues: Bob Cialdini (a social psychologist who studies social influence), Art Glenberg (a cognitive psychologist who studies embodied cognition), Bob Hogan (a personality psychologist who studies leadership and organizational behavior), Peter Killeen (an experimental psychologist who studies learning), Steve Neuberg (an evolutionary social psychologist who studies social cognition and prejudice), Mark Schaller (a social psychologist who studies culture and prejudice), and Quincy-Robyn Young (a clinical health psychologist who works with heart transplant patients). Each of these people has contributed to the scientific literature, and had thoughtful things to say about psychology’s possible geniuses.

Third, I will compare the lists my colleagues and I generated off-the-top-of-our-heads to a more rigorously generated list of eminent 20th century psychologists (Haggbloom, 2002). Eminence and genius are not quite the same thing, but I will also ponder the question of what makes for genius and eminence, separately and together.

Fourth, I will ask whether there is anyone who should have been on these lists whose ingenious contributions have either been forgotten in the modern era, or simply taken for granted after the field incorporated their ideas.

Finally, I will consider a question raised by my colleague Mark Schaller, who strongly opined that: “Who are the geniuses of psychology?” was a bad question. Instead, Schaller thought we should be asking: “What are the ingenious ideas generated by the field of psychology?” Part of the objection is this: Is it really fair to call any single scientist a genius, when science is a collaborative exercise in group intelligence, and almost any “discoverer” is likely to be standing on the shoulders of his or her fellow scientists? It turns out that this same question was a big one for Isaacson when he wrote his inspiring book about the geniuses of the computer revolution.

Part I: My top-of-the head list

Here is a partial list of the psychologists who first came to mind when I first pondered the question of psychology’s possible geniuses:

B.F. Skinner was the first person to come to mind for me. He was also the person most likely to be nominated by my expert consultants. According to one of my books on the history of psychology, a random sample of APA psychologists in 1970 ranked Skinner as the most important influence on contemporary psychology, and another poll placed Skinner as one of the 100 most important people in the world today (Hothersall, 1984). Three decades later, when over 1000 psychologists were asked to name “the greatest psychologists of the 20th century,” Skinner was still number 1.

Skinner was a brilliant man, who spent the better part of his career at Harvard, engaged in erudite debates with philosophers and cognitive scientists about the epistemological advantages of logical positivism and radical behaviorism. But Skinner’s most important contributions do not require a rocket scientist or an Oxford philosopher to understand. Skinner contributed, directly and indirectly, to behavioral technologies that indeed rival the digital technologies created by computer scientists – the principles of operant conditioning. At the simplest level, the idea is that people and other mobile critters (including dogs, rats, toads, and paramecia) repeat those voluntary behaviors that are followed by positive consequences, and stop performing those behaviors that are followed by negative consequences.

Skinner humbly noted that his major contribution was to take E.L. Thorndike’s Law of Effect seriously. But that is a little white understatement. What Skinner actually did was to rigorously and painstakingly lay out many of the principles of reinforcement, using his famous operant chamber (dubbed the Skinner box) to carefully document how different schedules of reinforcement influence how quickly an animal learns something, as well as how long it takes for that learning to extinguish. When he was running short out of reward pellets one day, he accidentally discovered that intermittent reinforcement can lead to behaviors that are highly resistant to extinction -- a fact that many parents learn the hard way (or more frequently never learn, but instead just keep digging themselves in deeper by occasionally reinforcing the very behaviors they want to stop). Another simple but critical principle that Skinner laid out is the importance of shaping – or training up complex and difficult behaviors out of simple responses using the principle successive approximations (see my earlier post on Turning mega-threats into micro-triumphs).

Skinner’s principles of reinforcement have been widely applied – in the schoolroom, the workplace, and in the treatment of various kinds of psychological disorder. Everyone who has a kid, or an employee, or wants to control themselves, should know these principles by heart, and more importantly, practice them.

Skinner also advocated the use of “teaching machines” using “programmed learning” – in many ways anticipating the power of modern computers to reward every step of the learning process (and to command a child’s attention), in ways that are nearly impossible, even for a one-on-one tutor, much less a teacher with a class full of 25 different students working at different paces.

Part of Skinner’s appeal came from the fact that he was an engaging writer. He spent a year trying to make it as a novelist before returning to graduate school in psychology, and one of his best known books was a novel about a behaviorist Utopia that he wrote many years later (which he called Walden 2).

Here are a few suggested readings from Skinner’s extensive bibliography:

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Skinner, B. F. (1956). A case history in scientific method. American Psychologist, 11(5), 221-233.

Skinner, B. F. (1958). Teaching machines. Science. 128, 969-977.

Skinner, B. F. (1976). Particulars of my life. New York: Knopf.

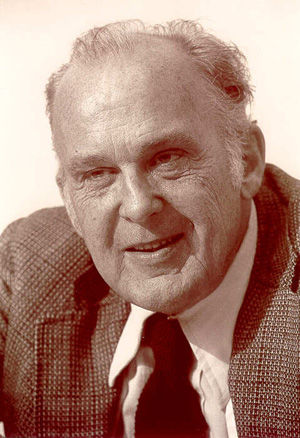

Donald Campbell earned his Ph.D. at Berkeley in 1947, and spent the biggest part of his career at Northwestern University, where he made major intellectual contributions to psychological methods and theory. His book “Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research” (with Julian Stanley) is a classic, as is his paper on convergent and discriminant validation (with Donald Fiske). In his 1975 presidential address to the American Psychological Association, Campbell helped push psychologists to begin considering evolutionary factors in their research on human social behavior. He was the ultimate interdisciplinary scholar, bridging psychology, sociology, biology, political science, and philosophical. One of his brilliant interdisciplinary lines of work promoted the idea of evolutionary epistemology –that scientific ideas survive or perish according to the same principles of blind variation and selective retention as do biological species.

Campbell, D. T. (1975). On the conflicts between biological and social evolution and between psychology and moral tradition. American psychologist, 30, 1103-1126.

Campbell, D. T., and Fiske, D.W. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological bulletin, 56, 81-105.

Campbell, D. T. (1960). Blind variation and selective retention in creative thought as in other knowledge processes. Psychological review, 67, 380-400.

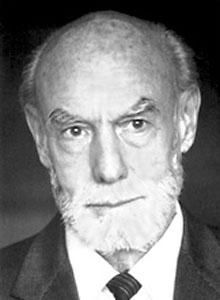

Roger Sperry and Michael Gazzaniga. Roger Sperry was a professor of psychobiology at Cal Tech, where he conducted research on “split brain” patients (who had had their corpus callosum severed to reduce seizures). That work won Sperry a Nobel Prize. Michael Gazzaniga was Sperry’s doctoral student, and he had primary responsibility for running much of that research. They found that patients who had their brain’s hemispheres separated responded very differently when a stimulus was presented to the right or left hemisphere. If shown a frightening picture to the right (less verbal) hemisphere, a patient would experience fear, but then his left (more verbal) hemisphere would attempt to explain the feeling (inventing an incorrect explanation, unaware of the actual cause). One patient, whose left hemisphere was unaware that his right hemisphere had seen a very scary picture, explained his own feeling of fear as due to Gazzaniga’s seeming to be in a bad mood that day. The most important insight from this work was that the brain’s processing is not a unitary process, but that different brain modules “think” about different inputs, or about the same inputs in different ways, at the same time. This work has had a great deal of influence on how psychologists now think about the relationship between the brain and the mind (see Kenrick & Griskevicius, 2013). There’s not just one self inside our heads.

Sperry, R. W. (1968). Hemisphere deconnection and unity in conscious awareness. American Psychologist, 23(10), 723.

Gazzaniga, M. S. (1967). The split brain in man. Scientific American, 217(2), 24-29.

Gazzaniga, Michael S. (1987). The Social Brain: Discovering the Networks of the Mind. Basic Books

William McDougall – McDougall wrote the first textbook on social psychology in 1908. Actually, he was tied for first, because E.O. Ross, a brilliant sociologist, also wrote a book titled “social psychology” that year). Whereas Ross focused on group level processes (such as fads and crowd behavior), McDougall focused on individual motivation. Following Charles Darwin’s classic book on emotions, McDougall argued that human decisions are strongly influenced by social instincts and their associated emotional components. McDougall’s list of primary instincts included flight (associated with the emotion of fear), repulsion (disgust), curiosity (wonder), self-abasement (subjection), self-assertion (elation), pugnacity (anger), and the parental instinct (tenderness/nurturance). McDougall’s instinct-based approach was rejected by early behaviorists, and he himself never established an influential research program. However, ethologists revived the study of instinctive behavior as a profitable research paradigm later in the 20th century (see Alcock, 2001, 2013). And modern psychologists have revived not only the general utility of thinking about instinctive control of behavior (Pinker, 1994), but also the usefulness of differentiating specific motivational-emotional systems, along lines that follow some of McDougall’s basic assumptions (see Bugental, 2000; Kenrick et al., 2010; Plutchik, 1980).

McDougall, W. (1908). An introduction to social psychology. Boston: J.W. Luce & Co.

To be continued

My initial list also included four brilliant psychologists who I know personally. I will talk about their contributions, and why I regard them as candidates for the genius list, in my next blog post. And then I will talk about some other candidate geniuses nominated by my brilliant friends. Stay tuned.

Douglas Kenrick is author of: -The Rational Animal: How evolution made us smarter than we think and

-Sex, Murder, and the Meaning of Life: A psychologist investigates how evolution, cognition, and complexity are revolutionizing our view of human nature.

References:

Alcock, J. (2001). The triumph of sociobiology. Oxford University Press.

Alcock, J. (2013). Animal behavior: An evolutionary approach. (10th edition). Sinauer: Sunderland, MA.

Pinker, S. (1994). The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language. New York: William Morrow.

Bugental, D. B. (2000). Acquisition of the algorithms of social life: a domain-based approach. Psychological bulletin, 126(2), 187-219.

Haggbloom, S. J., Warnick, R., Warnick, J. E., Jones, V. K., Yarbrough, G. L., Russell, T. M., Borecky, C. M.; McGahhey, R.; Powell III, J. L.; Beavers, J.; & Monte, E. (2002). The 100 most eminent psychologists of the 20th century. Review of General Psychology, 6(2), 139-152.

Hothersall, D. (1984). History of psychology. New York: Random House.

Kenrick, D.T., & Griskevicius, V. (2013). The rational animal: How evolution made us smarter than we think. New York: Basic Books.

Kenrick, D. T., Griskevicius, V., Neuberg, S. L., & Schaller, M. (2010). Renovating the pyramid of needs contemporary extensions built upon ancient foundations. Perspectives on psychological science, 5(3), 292-314.

Plutchik, R. (1980). A general psychoevolutionary theory of emotion. In R. Plutchik & H. Kellerman (ed.). Emotion: theory, research, and experience. (Vol. 1:Theories of emotion) pp. 3-31.

Photo sources:

Donald Campbell: Wikipedia, listed as Fair Use, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Donald_T_Campbell-lg.jpg

Michael Gazzaniga. His own publicly available image from his lab. https://www.psych.ucsb.edu/people/faculty/gazzaniga

William McDougall: From the British Psychology Society’s webpage.

http://www.bps.org.uk/what-we-do/bps/history-psychology-centre/history-…

B.F. Skinner: Wikimedia commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:B.F._Skinner_at_Harvard_circa_1…

Roger Sperry: Wikipedia: Listed as Fair Use