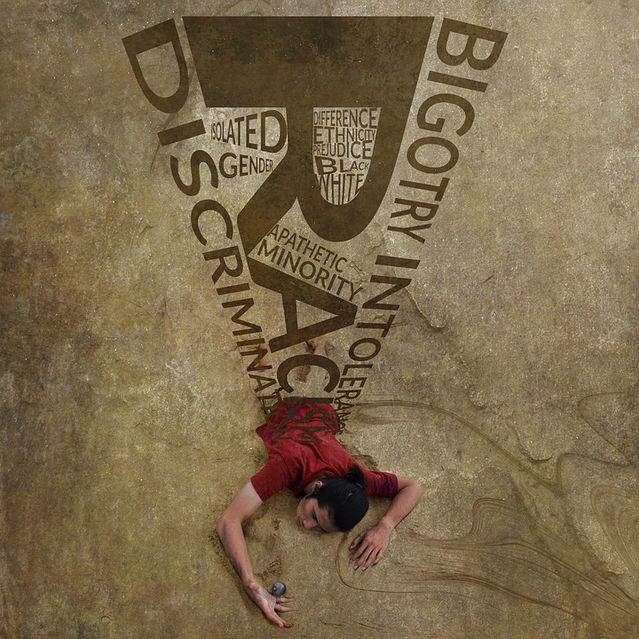

Bias

Being Biased Impairs Brain Processing and Disrupts Learning

Neuroscience of group bias and implications for the modern workplace.

Posted September 12, 2017

An unconscious mind is an efficient machine. Evolution has gifted our brains with the remarkable ability to fill in the blanks based on computed probabilities of past decisions and experiences. It’s what psychologists refer to as heuristics. And without them, it would be almost impossible for us to exist.

But as much as heuristics are important for guiding our judgments and decisions, these mental shortcuts result in certain psychological blind spots. And these blind spots give way to a host of different social biases. Such hidden social biases, we know, are bad for group functioning and team performance.

This idea has become more mainstream in the past five years. Big organizations have caught on. Google has taken an active stance to mitigate bias in the workplace. Their slogan, “Debiasing our biases,” is not a mere HR tagline, but instead, points to what we know about the plasticity of the human brain: We can override certain automatic heuristic-based responses.

It appears, according to Google at least, that we can outsmart our own biases.

Bias in the Workplace

Managing bias in the workplace is critical to the well-being of individual employees, as well as the success of broader organizations. Diversity and inclusion are key drivers that are becoming more integrated into the strategic vision of future-oriented workplaces.

Diversity comes in many forms: cultural, ethnic, gender, status, experiential, educational, etc. But no matter what form it comes in, the chief benefit of diversity is simple: being exposed to different perspectives drives innovative thinking and optimizes performance.

The Stubbornness of Our Biases

As much as the debiasing efforts have made headway in improving team performance, our heuristic-based thinking is stubborn, even when they lead to negative outcomes. Perhaps most dangerous of all, they promote a sort of primal group psychology—the quick and easy differentiation between “us” and “them,” and the sense of familiarity that this comes with.

This type of thinking inculcates prejudice and discrimination. We know this anecdotally and from decades of empirical psychological research. It’s an obvious truth that biases are bad for the targeted others. But now there’s new scientific evidence suggesting this thinking is also bad for the biased person.

Taking this a step further, my team and I conducted a study where we predicted that being biased can actually be detrimental to a person’s own implicit brain functioning. We did this by setting up an experiment where we had people perform a learning task while being observed by other people—one ingroup member and one outgroup member.

The Experiment: Red Shirts vs. Blue Shirts

For the study, we first created an artificial intergroup context in the lab by arbitrarily placing participants into two groups: the red-shirts and the blue-shirts. Importantly, the “minimal grouping” that we did was based on a trivial categorization: the number of dots people estimated in an image.

After donning their colored shirts, participants then completed two rounds of a performance learning task—once while being observed by an ingroup member (red shirts) and once while being observed by an outgroup member (blue shirts). To incentivize performance, they were told the better they did, the more money they would earn.

As they completed the task, participants’ neural patterns were tracked and recorded at the moment they received learning feedback on the task. The signal we targeted in the brain, called the feedback-related signal, is associated with adaptive learning and goal-motivated performance. For optimal learning during performance, a larger signal indicates the brain is doing a good job at processing feedback information and learning from it.

So, our question for the experiment was this: Does the strength of the brain’s learning signal differ depending on whether a person is being observed by an ingroup member versus an outgroup member? In other words, would you and your brain learn better (or worse) on a task if you were being observed by a fellow red shirt (or an outsider blue shirt)?

The Results: Impaired Brain Processing (But There's a Silver-lining!)

We found just that. When participants were performing in the presence of a red-shirted ingroup member, their brain’s learning signal appeared normal, as it always does when people perform on their own (if anything, the signal was heightened).

But when participants did the same task in front of a blue-shirted outgroup member, this same signal (in the same brains) was drastically muted. What’s more, the most biased people showed a learning signal that was effectively turned off in the presence of an outgroup member. Simply put, for these people, the brain wasn’t learning as effectively in the presence of an “outsider.”

Why?

The reason is that we care much less about what outgroup members think of us and our behavior. It is this general lack of motivational interest that caused the learning signal in the brain to switch off in biased individuals. And this held true even though people were motivated to perform well and make money. It appears that we will harbor biases even if doing so comes at a personal cost of impaired brain functioning (and reduced dollar earnings).

It’s those damned stubborn biases.

Fortunately, there’s a silver-lining to this research story. The minimal groups that were created in the study (the red shirts, blue shirts) consisted of both males and females from different ethnic, religious, and educational backgrounds. The fact that our lab-constructed biases overrode the salient sources of real-life prejudice (gender, ethnicity, etc.) tells us that these biases can be turned on and off.

With the right frame of mind, we can de-bias even the most stubborn of biases.

Implications for the Workplace

Diversity in teams is paramount to modern workplace success. Employees need to perform optimally and learn effectively for an individual and collective benefit. However, if a person harbors certain unconscious biases while attempting to perform in a diverse team, they’ll end up under-performing and under-learning.

Moving forward, ridding ourselves of bias in the workplace (and elsewhere) means good things all around. If us researchers can create meaningful groups using red shirts and blue shirts in a laboratory context, then this means our brains are highly malleable in how they represent concepts related to group membership and social categorization.

In sum, as much as our innate heuristics benefit us as a species, what is even more remarkable is our human ability to learn and change certain default responses. It’s our learning brain that can outsmart those damned stubborn biases.

So remind yourself of your amazing learning brain, and don’t worry next time about your decision over whether you should wear your favorite red shirt or blue shirt to work. With the right frame of mind, it’s all purple anyway.

References

Hobson, N. M., & Inzlicht, M. (2016). The mere presence of an outgroup member disrupts the brain's feedback-monitoring system. Social Cognitive Affective Neuroscience, 11, 1698-1706.