Teamwork

Communication and Collaboration: Keys to Good Leadership

It takes special efforts to inspire people and to learn from them.

Updated June 11, 2024 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Key points

- Communication and collaboration involve complex, ongoing exchanges; they are not just simple one-offs.

- The give and take that occurs during communication is itself a form of collaboration.

- Leaders listen as much as they talk, since leadership is a two-way street (and sometimes a multilane highway).

- People are more inclined to collaborate when they see that leaders appreciate their ideas.

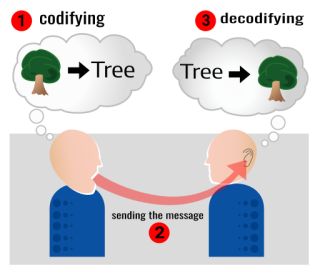

We tend to think of communication and collaboration as natural outcomes of working together. As soon as two people (or a hundred or a thousand) start working in tandem, they necessarily talk, share information, and exert themselves towards some common objective. However, this is a misconception. Such circumstances reduce the exchanges that we have with other people to a back-and-forth with no purpose other than increasing each other’s knowledge—and, hence, helping to get on with the job.

But effective communication and collaboration can be much more. By talking and sharing information, we change people’s minds, excite them to join us, and encourage them to perform at a level that they could not have imagined on their own. In this sense, communication and collaboration are instrumental. They are strategic, and can alter the landscape in our favor. In my practice, I’ve seen how everyday leaders deploy communication and collaboration (in a variety of forms) to create and promote new possibilities—literally, to change outcomes.

Everyday leaders rely on communication and collaboration as ongoing, extensible processes that can last for the duration of a project as it unfolds. These leaders are always learning. They listen as much as they send out directives or speak before their assembled employees. They understand that the process itself brings people closer, raising their spirits and level of commitment. Whatever else happens, such leaders ensure that information flows in as many directions as necessary to keep people on board and engaged. This type of sharing creates crucial, mutually supportive relationships.

Yet while I address communication and collaboration together, I don’t see them as the same. That is, you can communicate without collaborating, though the former may (over time) give rise to the latter as people are drawn towards the same orbit. Communication that precedes collaboration will, of course, continue as the one gives way to the other. But in essence, when you communicate, you create an occasional relationship that does not require a shared objective; there may be one, though we often communicate with opponents.

On the other hand, when you collaborate, there is always a common objective, even though people may not agree on everything. Think of Republicans or Democrats— they fight internally, but each party shares the overriding objective of gaining the most power.

Yet notwithstanding their different conceptual outlines, communication and collaboration share some important features. For the everyday leader, both should be the product of careful calculation: What should I say? When? To whom? For what purpose? The opportunity to share information and ideas, and to learn from other people, should never be approached casually. There will not be that many chances for a do-over, so it’s important to do it right the first time and to make a good impression. Even as you learn by doing, consider every opportunity for an exchange as a type of elevator speech: Get it right, and good things can develop for there.

Whether a situation involves communication and/or collaboration, the point is to create synergy between or among the people involved. Such people should develop habits of mind—in effect, they should be trained—to act together with you in ways that would not have otherwise occurred. They may also be trained to act together in teams, producing a far greater impact than anyone might have on their own. Everyday leaders need to create such synergies, since their resources are often limited.

Several of my clients have experienced communication and collaboration in action, that is, in their active modes beyond mere information exchange. These leaders’ ultimate objective was to engage people, and raise their interest in a project. They did so creatively and economically, based on what they could offer in return. In this regard, they understood that communication and collaboration are well-lit two-way streets (and sometimes the discursive equivalent of multi-lane highways). They’re not some back-county road with no yellow line, marked only with signs that announce the leader’s intentions.

One of my clients, a young lawyer, used effective communication to promote a project in his firm, drawing his partners into an ad hoc collaboration. He aroused enough interest so that they asked him to collaborate. He was psychologically adept. He knew what the group wanted (and, obviously, provided grounds for them to believe that they’d get it). Most important, he used communication to enhance his profile and inspire trust in his leadership.

Another of my clients, a young woman, learned how to deploy communication strategies to outflank the competition. Along the way, she discarded strategies that worked in her family but clearly did not work in a wider, more impersonal, less matriarchal environment. She had to adjust her modus operandi based on the feedback she received.

Feedback is a form of collaboration! In the process, she jettisoned inherited notions of how to get her points across. In effect, she grew up— and, hence, grew into her position as a leader through spontaneous, intellectual give and take.

Even when we do not elicit give and take, we should use it effectively when it (necessarily) occurs.

Finally, another client, an investment manager, had to convince his team through effective communication that they ought to collaborate on a project that made them uncomfortable. He did it by demonstrating a likely impressive payoff. He made logical sense, encouraging them to think past their (somewhat irrational) reservations.

So, as you think about these everyday leaders, consider these concerns:

- Both communication and collaboration are instruments of effective leadership, providing opportunities for a two-way exchange of information and ideas.

- They help leaders draw people closer to how such leaders hope such people will think.

- They create a type of synergism both within organized teams and on an ad hoc basis among people at large.

- Leaders should calculate how/when/to whom they intend to communicate, since do-overs are not always possible and no opportunity should be wasted.

- Communication is an ongoing process, not just a one-off, and continues even after it gives way (if it does) to a collaboration.

The people I have described were not experts in communication. They learned along the way. They discovered that without effective communication and collaboration, they could not succeed at effective leadership. Leaders are always generating ideas and improving their ideas based on what they learn from others.