Environment

Identifying Your Triggers

Understanding and taming your reactivity, part 2.

Posted February 26, 2021 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

In last month’s post, we looked at ways that our rational brains can sometimes get hijacked by our emotions. When we’re flooded with these emotions, we process inputs through the more basic part of our brain and not through the more sophisticated "executive management committee," the prefrontal cortex. We also saw that, to get back in control, we need to take time out to reset before re-engaging.

Whether our responses are epitomized by over-reaction or shutting down, recognizing when we’re flooded and when to take time to emotionally balance is key. Apart from "calming down," it also gives us the chance to identify our own individual physiological responses that are the telltale signs that we’re on the path to an out-of-control moment.

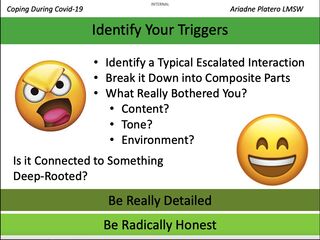

Equally important is the ability to identify our triggers. This will allow us to anticipate and, eventually, to make decisions that will help to avoid these same pitfalls in the future. Let’s look at how triggers can be identified by putting ourselves in detective mode and being methodical.

Step One: Identify an example of a conversation or disagreement when you’ve found yourself being very reactive or quick to anger. Choose a situation when an upset reaction was not reasonable and don't spend too much time searching — you’ll likely find that you will often have the same cycle of interaction with a particular partner regardless of the topic. Recently, I asked a couple to take note of one of their frequent escalated arguments so that we could analyze their cycle of interaction and begin to identify their triggers. They came into their next session saying that they hadn’t been able to identify an incident, but that they’d had a massive argument on the way to our session regarding picking up coffee. Bingo. We used that outsized spat over the minor decisions involved in getting their morning brew. They soon saw that the patterns were familiar and replicated in all their angry interactions.

Though I’ve never really liked the phrase “If it's hysterical, it's historical,” as it seems a little glib, I recognize that there’s truth to it. If you find yourself reacting to a statement or question in an overblown way, there’ll be something deeply rooted in the content, environment, or delivery of the interaction which triggered you.

Step Two: Take the escalated argument and start to break it down into composite parts. Take turns thinking through what your responses to each other entailed, like slowing a movie down into freeze frames. What was the conversation starter? What happened next? Think separately about content, tone, and environment. The content is the subject and the details of what was said. The tone includes volume, as well as meaning added by sarcasm, mocking, or any other layered aspect of the delivery. The environment can mean the mental or emotional place either of you was in at the time — tired from a night up with the children, stressed at the end of a particularly tough work week, on edge as your mother-in-law just arrived for a week’s stay. There are all kinds of things that can impact how we give or receive information.

Step Three: Once you’ve come up with a sense of what the individual parts of the interaction are made of, then reflect. Get really detailed. And get really honest. I’ll give a simple example: One member of a couple is going on a business trip and asks their partner who is staying home about something going on while they’re apart. The person at home snaps back, irritated, and says something about how the person traveling is always leaving, so what do they care what happens at home anyway. The traveling partner becomes angry because they see this as a necessary part of their job and keeping the job is part of the agreed-upon plan for future stability. Both partners are angry with each other, retreating aggrieved and smarting to their respective corners. They have a fraught separation.

What happened? Simplifying, the traveling partner had no specific agenda but the one staying at home had a history of feeling abandoned, so that, even though there was no specific reason that this trip indicated an abandonment, nevertheless those old familiar feelings were uncontrollably evoked by the sight of a suitcase being packed or the knowledge of an impending departure. The trip, the suitcase, or the prospect of being alone are the triggers here and derail what could have been a calm moment of connection as the couple prepared to spend time apart.

Step Four: What can you do with this information once you have it? It is important for both individuals to speak honestly and to listen openly; to share earlier searing experiences so the other can understand their impact; to brainstorm about how to ensure a similar situation unfolds differently next time; to discuss how to support each other in learning a different approach and reaction to these incidents.

The goal here is not to never disagree. The goal is to be able to disagree while still processing through your frontal lobe and without resorting to your Paleolithic brain; to argue in a reasonable way that, ultimately, brings you a greater understanding of each other and closer together. Renowned couples therapists and theorists, John and Julie Gottman, speak of “failed bids for connection.” These bids for connection come in all sizes and I think of frequent escalated arguments as larger versions of these failed bids.

What if your partner won’t cooperate? Working together is better, but understanding your own triggers is within your control, has great value, and is a goal in and of itself. Even if only one member of a couple changes their behavior, it will inevitably change the interaction as a whole. And maybe, after witnessing your growth, your partner will join you in the exercise next time.

References

John Gottman, Ph.D. (1999). The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work. New York, NY: Harmony Books