Bias

Recognizing Politically-Biased Social Science

Commentary: How not to test a hypothesis that no social scientist ever proposed.

Posted December 1, 2021 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Political biases threaten the validity and credibility of social science research on politicized topics.

- A recent paper found that politics did not influence the replicability of a handful of studies.

- Those findings were based on sample sizes too small to be meaningful.

- They also seem, yet actually fail, to refute a hypothesis no social scientist ever proposed.

Political biases constitute a permanent threat to the validity of social science on politicized issues because:

- Almost everyone in the social sciences holds politically left beliefs, including an extraordinary overrepresentation of radicals, activists, and extremists (see this reading list for more on this and other topics addressed in this essay).

- Until that changes, there is always a potential for those political beliefs to influence almost every step of the research process, including but not restricted to what gets studied, funded, and published, how studies are designed and interpreted, and which conclusions become widely accepted within a field.

- Unless active steps are taken to limit such biases, they are likely to run rampant; many social scientists embrace the idea that infusing social science with activist agendas is justified.

This figure (adapted from Honeycutt & Jussim, 2020) shows many of those threats. (Short essays on these topics can be found here, here, and here.).

A team of researchers stepped into this swamp of credibility threats with a study (they called it “two studies” but, as you shall see, it is really one study) that constitutes a case study in how to go wrong when trying to test hypotheses about political biases.

Are Left-Leaning Studies Less Replicable?

Reinero et al (2020) proposed the following hypothesis: If political biases influence social science, then lower standards should be applied to left-leaning articles than to right-leaning articles. If so, then left-leaning findings should prove less replicable than right-leaning findings.

To test this hypothesis, Reinero et al (2020) had six doctoral students code whether 194 replication attempts involved topics with a political slant; they also paid 511 laypeople (Mechanical Turk workers) to code the studies. Regardless of who did the coding, replication success/failure was unrelated to whether the articles were left- or right-leaning. Two of the authors claimed, “our study suggests that political bias may not plague psychological science to the extent that it dominates many other domains of society.”

Not So Fast

Bad hypothesis. In my view, this effort was misguided out the gate. There is extensive literature on how political biases manifest in the social sciences. Biases in replication are nowhere to be found in that literature.

Bad hypothesis, badly tested. Reinero et al’s findings were based on a sample of studies too small to detect any left/right differences in replication even if they exist. Their total pool was 194 studies. However, no one ever predicted political bias on apolitical studies, so all apolitical studies should be thrown out as irrelevant. The relevant sample is the left- and right-slanted articles. Their graduate student coders identified 20 left-leaning studies and eight right-leaning ones. Their paid coders identified six liberal and four conservative studies. These numbers are so small that anything produced on their basis is meaningless.

They Only Conducted One Study

Reinero et al framed their paper as if they performed two studies. Typically, studies are considered separate if they involve different samples. However, in the Reinero et al paper, the “two” studies were based on the same sample of 194 replications. The only difference was who did the coding for study politicization: in “Study 1” it was six graduate students; in “Study 2” it was 511 laypeople.

Having two sets of coders rate one set of studies does not constitute “separate studies.” This is what's known as a “robustness check,” addressing whether the same results hold up when different people do the political coding.

Political Amateurs?

Political scientists, political journalists, and political party officials are experts on politics; graduate students and Mechanical Turk workers are generally not. Whether such political amateurs had the expertise to make these judgments with any validity was not tested and therefore remains unknown. In the absence of either use of such experts or validity evidence for the coders they did use, there is no reason to have confidence in the validity of the coding.

One can see how badly this study failed to capture politicized research simply by looking at articles characterized as either liberal or conservative, which was provided in their supplementary materials. Here are two titles:

- Liberal: "Reading literary fiction improves theories of mind."

- Conservative: "Influence of popular erotica on judgments of strangers and mates."

These topics pale in politicization compared to many modern culture war issues, such as white supremacy, racial and gender inequality and discrimination, the sex and gender binary, immigration, abortion, colonialism, and climate change. No one I know of who has ever addressed political biases (see reading list) has argued that they would manifest on tepid topics.

Spin

Their report also includes some examples of what is plausibly considered "spin" that may serve to make the work appear stronger than it really was. The abstract refers to the 194 replications and the total number of human participants in these studies (over a million). Impressive, right? Definitely far more impressive than the far more relevant sample sizes of 47 and 10 for their number of politicized articles (and only eight and four conservative ones), which were not reported in the abstract.

Claiming they reported two studies when what they really performed was a robustness check on a single study is also plausibly considered spin. De Vries et al (2019) referred to “spin” as occurring when researchers emphasize supportive secondary results and downplay unsupportive primary results; it is plausible to also consider “spin” as researchers’ emphasizing features of their samples, design, or analyses that sound more impressive than what was actually relevant to test their hypotheses.

Citation Biases?

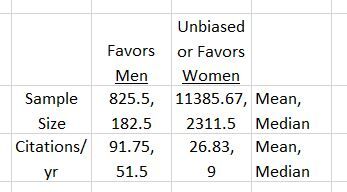

Reinero et al also found no tendency for citations to favor the “liberal” over the “conservative” findings. But, of course, this should work on hot-button issues, such as racism and sexism, not on the politically tepid issues such as the effects of reading literary fiction. For example, Honeycutt & Jussim (2020) examined both the sample size of and citations to articles showing or failing to show gender biases in peer review of articles and grants. As described here, we first identified every paper we could find examining gender bias in peer review, then excluded papers that were either too recent (because there was not enough time for citations to mount) or whose findings were muddled (rather than clearly showing biases favoring men versus women versus no bias). The main findings from our citation bias analysis is shown here:

Studies finding biases favoring men are cited 3-5 times as much as are studies finding biases do not favor men. Furthermore, studies finding biases that do not favor men average sample sizes at least 10 times greater than those finding biases do favor men. Let's smash the patriarchy (whether or not the evidence is that it needs smashing).

Bottom Lines

Despite its many flaws, Reinero et al’s result is probably valid—which is why no social scientist arguing for political biases has ever argued that they manifest as replicability differences between left vs. right-affirming findings. Nonetheless, in my assessment, it constituted an extraordinarily weak test of this badly-derived hypothesis. It flatters the overwhelmingly left researchers who populate social psychology by appearing to vindicate the field from charges of political bias despite failing to do so.

Final Notes: I was invited to collaborate with one of the authors on what eventually became the Reinero et al project before it was initiated. I refused because I saw it as foreseeably doomed to constitute a bad test of a badly-derived hypothesis. An earlier version of this critique was sent to Reinero et al, requesting that they identify any errors in this critique. I received a reply explaining why they disagreed with much of this critique and claiming their work was well-done and justified. Nothing in this blog, however, was identified as actually inaccurate.

Reading List on Political Bias in Social Science can be found here.

References

De Vries, Y. A., Roest, A. M., de Jonge, P., Cuijpers, P., Munafo, M. R., & Bastiaansen, J. A. (2018). The cumulative effect of reporting and citation biases on the apparent efficacy of treatments: The case of depression. Psychological Medicine, 48, 2453-2455.

Honeycutt, N & Jussim, L (2020). A model of political bias in social science research. Psychological Inquiry, 31, 73-85.

Reinero, D. A., Wills, J. A., Brady, W J. Mende-Siedlecki, P., Crawford, J. T. & van Bavel, J. J. (2020). Is the political slant of psychology research related to scientific replicability? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15, 1320-1328.