Bias

Confirmation Bias: Real Bias or Delegitimization Rhetoric?

Actual confirmation bias versus ad hominem insult.

Posted August 7, 2019 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Confirmation bias is both a real phenomenon and a self-serving rhetorical bludgeon designed to delegitimize an opponent’s argument when one cannot refute it. In this post, I show how you can distinguish one from the other.

The Many Faces of Confirmation Bias

At its most general, confirmation bias refers to any of a variety of preferences for information that supports one’s beliefs, values, attitudes, politics, or morals. This manifests in any of a variety of ways. Cherry-picking refers to citing evidence that supports one’s beliefs or attitudes but ignoring evidence that conflicts with those beliefs or attitudes. Blind spots refer to being systematically far more aware of evidence or arguments that support one’s views than those that oppose them. Selective criticisms or selective calls for rigor involve requiring evidence that opposes one’s views to meet much higher standards to be considered credible than one requires for evidence that supports one’s views.

Cherry-picking and Blind Spots

It is usually difficult to distinguish between intentional cherry-picking and blind spots because we rarely have insight into a person’s intentions. Because they both manifest as failing to present contradictory information, I discuss them together. For example, consider a person who believes that discrimination against women is powerful and pervasive, and presents this study, titled "Science faculty's subtle gender biases favor male students" in a triumphant manner as if it ends the discussion.

What is wrong? It is a bona fide study and the title aptly conveys its main message. Nonetheless, a person arguing that discrimination against women is powerful and who presents only this study, or studies showing discrimination against women, can be justifiably accused of engaging in confirmation bias. Why? Because there are many studies showing that people are unbiased or even more biased against men than women and there are many other studies showing biases against women. The purpose of this essay is not to resolve the issue of how much discrimination there is out there. My point is that if one is arguing either for powerful biases against women and only cites studies showing biases against women, or against powerful biases against women and only cites studies showing no bias against women, and simply ignores evidence contrary to one's argument, one is pretty much a textbook case of confirmation bias.

I addressed a real-world scientific example of such a blind spot (or maybe cherrypicking) in a prior post. A recent Annual Review Chapter concluded that gender stereotypes are “inaccurate”—without citing any one of the 11 papers reporting 16 studies assessing gender stereotype accuracy.

Selective Calls for Rigor

Or consider a selective call for rigor. Every study and every academic paper can be criticized. Sometimes, however, imperfections in a paper, real or imaginary, especially when that paper is on some controversial topic, can and have been used in attempts to get a paper that has successfully gone through peer review retracted or the author(s) sanctioned. See my prior post regarding the curious case of Rapid Onset Gender Dysphoria, though there are many others. The point here isn’t that the papers can’t be criticized; of course, they can. But if papers meet the normal standards for publication (i.e., they pass peer review), then absent some sort of gross malfeasance (e.g., the data is shown to be fraudulent), calls to retract on the grounds of “flaws!” constitute selective calls for rigor; i.e., confirmation bias.

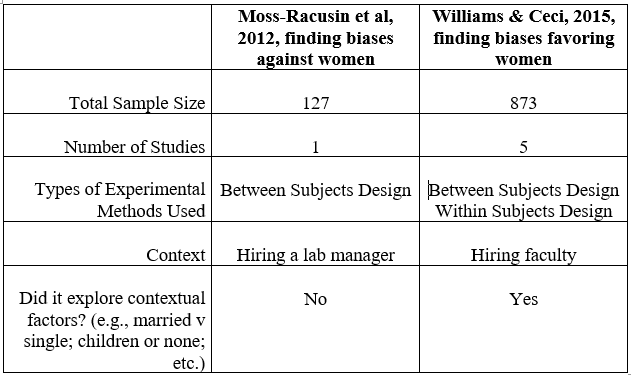

Or consider this essay published in The Chronicle of Higher Education. It extolled the Moss-Racusin et al paper (described above) for finding bias against women in academic STEM hiring as "rigorous," but criticized on ostensibly methodological grounds the Williams & Ceci studies that found bias favoring women. Interestingly, however, the Williams & Ceci was stronger on almost all widely-recognized and observable methodological grounds:

For example, one of the criticisms leveled at the Williams & Ceci paper in the Chronicle critique is that bias goes well beyond hiring. That is surely true, but it is a trivial criticism. No study can demonstrate anything about anything they did not study. Furthermore, the Chronicle essay extols the Moss-Racusin et al study as “rigorous.” Moss-Racusin et al also only studied hiring. This is an exquisite example of a selective call for rigor because if "only studied hiring" delegitimizes the Williams & Ceci study it should also delegitimize the Moss-Racusin et al study.

So, the actual confirmation bias can be demonstrated. One needs to show that the person accused of confirmation bias has systematically ignored evidence that fails to support their argument OR applies different standards when criticizing work they object to than when criticizing work they support.

Accusations of “Confirmation Bias” as Delegitimization Rhetorical Tactic

Thus, it is relatively simple to tell whether an accusation of confirmation bias is justified: Has the accuser presented evidence that the accused: 1. Cherrypicked; 2. Is blind to opposing evidence; or 3. Has engaged in selective criticism of research s/he opposes and fails to apply the same standard to research s/he supports? Or has the accuser presented any other reason to believe the accused privileges confirming over disconfirming evidence? If the answer is "yes" to any of these questions, then the accuser has at least presented some justification, some evidence supporting the accusation of "confirmation bias!" (Of course, simply presenting such evidence does not mean the accusation is true; the evidence could be itself mistaken, flawed, misininterpreted or misrepresented and needs to be evaluated for credibility in the same manner as any evidence ever put forward for any claim).

Often, however, the answer is "no" to all of these questions, in which case the accuser has done nothing but present an unjustified accusation. In controversies and debates, you see this frequently, where one person or one side simply flings accusations of “confirmation bias!” at the other side. In the absence of actual evidence of confirmation bias, this is just a gratuitous insult, a thinly-veiled ad hominem attack. It says, in effect, “In contrast to my pristine objectivity and rationality, you, my opponent, are biased. How do we know? The weight and strength of my arguments are readily apparent to any reasonable person. Only someone as biased, as obstinate as you, would not readily recognize the power and brilliance of my points!”

None of that will be stated quite that way, but, absent any evidence of actual confirmation bias on the part of one’s opponent, some variation of that is strongly implied in such accusations. Of course, in the absence of actual evidence that one’s opponent has engaged in confirmation bias, it is merely a gratuitous attempt to delegitimize one’s opponent’s arguments.

Actual Confirmation Bias Revealed in Vacuous Accusations of “Confirmation Bias!”

Actual confirmation bias during some disagreement or controversy often manifests during public disagreements as follows: A gratuitous accusation of “confirmation bias!” (i.e., one presented without evidence of such a bias) is greeted with support by onlookers. Let’s say Fred makes some controversial point – say, that unlimited immigration harms many racial and ethnic minorities in the U.S. Susan declares, “Your confirmation bias is on full display!”

Susan sounds oh-so-sophisticated, flinging this psychological buzz term at Fred as if it actually has some relevance. But absent showing that Fred actually engaged in some sort of biased analysis, it is just a vacuous insult. Therefore, those who pile on, by “liking” (say, on social media) Susan’s insult are implicitly engaging in actual confirmation bias: They are agreeing with her analysis, even though she did not present a shred of evidence to support it. And accepting no evidence as a good criterion for an empirical claim (in this case, “Fred is biased!”) is one of the most extreme forms of confirmation bias.

Although it’s beyond the scope of this post, the analysis fundamentally applies to almost any charge of bias–from purely cognitive biases, such as, for example, availability or representativeness biases, to charges of racism, sexism, or other -isms. Absent evidence of bias, the accusation is just a sneering ad hominem insult. It might even be true–the accused might be using the availability heuristic or be a racist–but absent presentation of evidence of bias, an accusation of bias is just an insult. And just as we do not legally convict someone of a crime based on accusations alone, nor should we condemn someone for “bias” absent evidence of such bias.

Bottom lines: Confirmation bias is a real phenomenon. Like any real phenomenon, to demonstrate its occurrence requires evidence. Absent presentation of such evidence, flinging accusations of “confirmation bias!” at one’s opponents is merely a rhetorical tactic of delegitimization; an ad hominem attack, and itself an illegitimate form of intellectual discourse.

I would be delighted for you to post a comment, but, before doing so, please read my Guidelines for Engaging in Controversial Discourse. Short version: Keep it civil (no insults or ad hominem, no profanity or sarcasm), brief, and on topic, otherwise I will take your comment down.