Education

Insights from Chemistry into how ‘Nudges’ Impact Decisions

Yes, Chemistry! Choice Engineering through Libertarian Paternalism Redefined.

Posted November 6, 2013

Many times every day we make choices, and these choices are not made in isolation. Choices can be influenced by our physical environment or even by written or spoken words.

Five years ago, in 2008, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein published a book about choices and choice influencers. Five years ago is old news, but this past summer, Thaler and Sunstein’s ideas again entered the public consciousness when it became known that the Obama administration was considering creating an American version of the United Kingdom’s Behavioral Insights Team.

Many articles and blog posts this past summer denounced governmental influence on behavior, which is ironic. To understand the irony, reread the first paragraph. No choice is made in isolation. (Thaler and Sunstein use the analogy of no choices being made in a vacuum on their website.) There is always something influencing choices you make. Even in the absence of some kind of Behavioral Insights Team, government action, without intention, influences choices people make.

In this post, I am going to explain choice influences in a new way, through concepts from chemistry. My only goal is for you to generate your own – informed – opinion about choice influences.

Nudges and libertarian paternalism: political swear words?

In their book, Thaler and Sunstein named certain choice influences “nudges.” They defined nudges as something that “alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives.”

Thaler and Sunstein also argued for the implementation of nudges by government, under the ideology of libertarian paternalism. Libertarian paternalism, simplified, is the promotion of influencers that guide better choices without force. What makes nudges that are part of libertarian paternalism a special subset of choice influencers is that they intentionally target choices people generally want to make anyway. In the words of Thaler and Sunstein, nudges “influence choices in a way that will make choosers better off, as judged by themselves.”

Consider the following examples to illustrate where nudges are used, and where they are confused.

You are at the pet store cash register, paying for your dog’s food and chew toys. As the cashier takes your card for payment, she asks you if you’d like to donate $1 to a charity benefitting homeless animals.

Charity donations at checkout are nudges that rely on the premise that once someone’s wallet is open, they are more willing to donate.

You are ordering fast food and, as you peruse the side item menu, you notice pictures of salads and apple slices.

Reframing how we order food is a nudge that will impact what food we choose to order.

A city mayor works to end the sale of large soda pops.

This example prohibits an option and is not an example of a nudge, even though Bloomberg’s campaign to ban soda has erroneously been described as a nudge gone too far.

Your employer changes your pay schedule from monthly to biweekly.

This could be an example of a nudge or also of a non-intentional choice influence. Thaler and Sunstein point out that people save more money when paid biweekly because two months a year, they receive three paychecks. But, the pay schedule could have been determined without the goal of encouraging employee savings.

Choice influences, even non-nudge influences, are everywhere.

Some media and blogger coverage of nudges from this past summer hyperbolized libertarian paternalism as a means to bigger government, and suggested that nudges – better called shoves – just take away the right to make our own choices.

Never mind what the dictionary says, this kind of nudge has nothing to do with a shove.

My education is in neuroscience and chemistry. The first time I learned about behavioral nudges, I immediately thought, “Oh, a nudge just lowers the activation energy for a decision you want to make anyway.”

Likening what a nudge does to activation energy requires a brief detour into chemistry, but the analogy is a good teaching tool to understand nudges and libertarian paternalism.

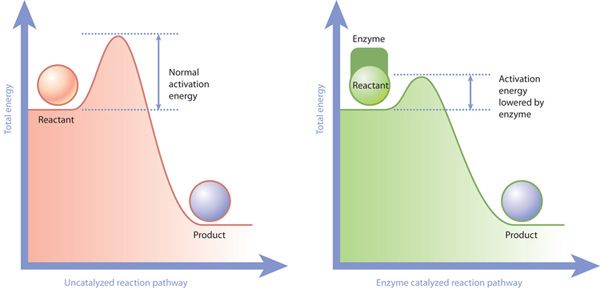

Activation energy is the amount of energy it takes chemical reactants to come together, react, and then form something new, called the product (red diagram).

Chemical reaction pathway and activation energy without (red) and with (green) a catalyst.

If reactants do not collide with enough energy to surmount the activation energy, the reaction will not happen. Simply put, the reactants have to bang into each other with enough energy to climb the hill, or they will not turn into product.

There are things that can be done to help "climb" the hill and therefore make the reactants more likely to combine and form product. One way is to decrease the activation energy by adding a catalyst. A catalyst lowers the activation energy for the reaction, making product formation more likely, but does not itself become part of the product. (In the green diagram, the catalyst is a special kind of protein called an “enzyme.”)

There are two important points to understand from this brief foray into chemistry. The first is that energy is required to make chemical reactions happen. There is a hill to climb in order to make new things. The second point is that the addition of a catalyst lowers that energy, making the chemical reaction more likely to progress to product. In other words, adding a catalyst makes the hill you must climb shorter.

Nudges catalyze choices, not force them. Maybe nudges should be renamed “choice catalysts” to avoid the connotation of shoving that the word “nudge” commonly engenders.

Let’s now look at how the activation energy of a chemical reaction can be related to how people make choices in a real life situation.

There really is no free lunch.

The choices people make -- for example about whether lunch should be a salad or something else -- can be thought of in terms of the activation energy diagram.

Pretend you are eating lunch in a cafeteria.

As soon as you pick up your tray and empty plate and start to look around, you are in the first part (“reactant”) of the activation energy diagram.

If one of your goals is to eat healthier, then the second part (“product”) of the activation energy program is you sitting down at a table with a plateful of salad.

The layout of the cafeteria affects foods choices; the layout defines the height of the “hill” you have to climb to make your decision.

If the first food station you pass after grabbing your tray is set up as a Belgian waffle bar with toppings, you have resist the waffles to end eating a healthy salad. Resisting a Belgian waffle bar is an example of a steep hill to climb, as in the red activation energy diagram. You still might end up seated with a plateful of salad, but you also might end up seated with an unhealthy (but yummy) Belgian waffle instead.

But if the first food station you pass after grabbing your tray is the salad bar, you are in the green activation energy diagram. Seeing the salad first makes it easier to choose it, and once you have made your choice of salad, resisting the Belgian waffle is easy. Also, maybe when you walk by the Belgian waffle stand, there is not enough room on your tray for a Belgian waffle, so you end up seated with a plateful of salad.

The layout of the dining hall could have been chosen randomly or deliberatively. Regardless of what the layout is, it is a nudge (a catalyst/enzyme in the chemistry analogy) and affects your meal choice. The layout of the dining hall did not force you to choose salad or the Belgian waffle or another food, but it did have an impact on your choice.

Like certain enzymes catalyze chemical reactions, certain nudges catalyze choices. But, this activation energy analogy is imperfect, because nudges are not as effective as catalysts.

People do not behave like molecules, and nudges do not force you to make a choice.

To further emphasize that nudges do not force you into making a choice, let’s take a look at two nudges that are considered successful by psychologists and economists.

These example nudges target choices such as the following:

1. Do you want to help decrease pollution in your community?

2. Do you want to help other people in a time of dire need, likely saving their life?

If these questions were put to a survey, I’d bet my lunch money that the answers would be yes.

The first example is from Denmark, which is host to a comprehensive website about nudges. According to the inudgeyou group, in Denmark, littering has decreased by almost 50 percent by way of manipulations like making garbage cans more obvious. This decrease is good of course, but it still means some people (about half) were not affected by the nudge and still choose to litter.

For the second example, consider organ donation. The United States has an “opt in” system; you have to sign yourself up for the organ donor registry. In other countries, it is an “opt out” system, where you have to indicate that you do not want your name on an organ donation registry. The actual effort required is very similar, if not the same: you have to fill out some kind of form. For opt out systems, the percentage of people who are on organ donation registries is 82 percent, while for opt in systems, it is only 42 percent.

82 percent is high, but everyone did not decide in the direction of the nudge.

Do libertarian paternalism and nudges have a role in government?

While remaining informed about what our government is doing is of course paramount, nudges do not force us to choose a certain way. Nudges are unavoidable, regardless of their origin, and suggestions that governments avoid them in essence require the banning of government itself.

The answer to this question about libertarian paternalism and nudges is that it is your decision.

Image source: Nature Education