Depression

Depression, Creativity, and Leadership

Part 1: Is depression an impediment or contributor to achievement?

Posted March 2, 2021

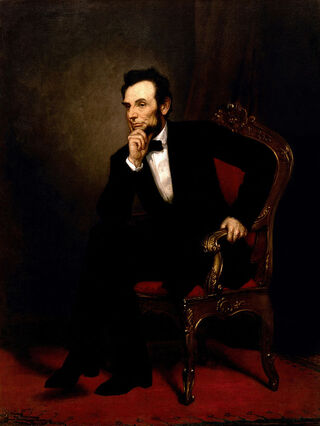

Abraham Lincoln’s tendency toward what was then called "melancholy" was well known by his neighbors in New Salem, Illinois. In his mid-twenties, after a woman to whom he felt close died of typhoid, he led an isolated life, spent long periods of time alone in the woods with his gun, and wrote gloomy poetry. At one point, the local justice of the peace and his wife convinced him to move in with them, but after a couple of weeks of being cared for, he remained morose. Though he occasionally sought merriment with his friends, he confided to one colleague that his mood was such that he dared not carry a knife.

Five years later in 1840, the young politician was so troubled that neighbors removed all the razors and sharp objects from his home. He requested help from a doctor, with whom he began to spend several hours a day. At one point, records from a Springfield pharmacy indicated that he sought pharmacologic relief with various medicines including sedatives, camphor, and mercury-based "blue mass" pills. (The latter, which he later discontinued, contained roughly 100 times the modern EPA guidelines for mercury; it has been speculated that mercury poisoning may also have contributed to his depressive symptoms, and anger outbursts, as well as tremor and difficulty walking.) Feelings of failure and doom, as well as fatigue interspersed with agitation and thoughts of death haunted him his whole life, even as he struggled with the great issues of his day, presided over the greatest crisis in the country’s history, and ultimately saved his nation (1).

The list of historical political and military figures who appear to have suffered from depression goes on and on, including Lincoln’s contemporaries Benjamin Disraeli and William T. Sherman, later notables such as Winston Churchill, writers over the decades (Ernest Hemingway, J.K. Rowling), and modern celebrities (Jim Carrey, Eminem, Anne Hathaway). Articles about the possible relation of depression to success in politics or the arts have taken two general views—that these people were able to overcome their depression and go on to greatness, or alternatively that something about their mood disorder aided them in the process.

One article on Lincoln, for instance, described three stages which he went through — fear, engagement, and transcendence — and argued that "Whatever greatness Lincoln achieved cannot be explained as a triumph over personal suffering. Rather, it must be accounted an outgrowth of the same system that produced that suffering … Lincoln didn't do great work because he solved the problem of his melancholy; the problem of his melancholy was all the more fuel for the fire of his great work" (1).

In this post, we’ll look at this latter possibility: Is there something amidst the suffering of depression that might be of positive value and lead to achievement?

In this first of two parts, we’ll look at the evidence associating depression with creativity and attainment, and the argument that the ubiquity and evolutionary persistence of depression suggest that it might be useful. In the second part, we will look at possible cognitive mechanisms by which depression might help achieve such goals. We will focus on major depression; the clinical features of bipolar disorder and the data about their frequency are sufficiently different that we’ll explore them in the future.

Studies of depression and creativity

The seductive notion that a depressed mood is associated with greatness goes back at least as far as Aristotle, who believed that "Great men are always of a nature originally melancholy" (2). The notion of the "neurotic genius" plagued by anxiety and depression continues to this day. Not surprisingly, it has generated more modern studies of a possible relationship, which interestingly, when excluding bipolar disorder, have sometimes been negative.

In an often-quoted study, psychiatrist Nancy Andreasen found "a higher rate of mental illness, predominantly affective disorder, with a tendency toward the bipolar subtype" in a group of 30 writers compared to controls (3). Alternatively, a study of 40 writers, 40 musicians, and a similar number of controls found no differences in measures of mental illness and stress (4).

A 2020 study found that artists were more likely to have vulnerabilities such as tendencies toward anxiety and depressive symptoms, as well as resources such as ego-resilience and hope, compared to non-artists (5). Modern studies, then, have shown mixed results about the possible relationship of depression and creativity.

The evolutionary argument for depression

Even though many of the features of depression such as fatigue, decreased appetite, and libido would seem to have negative evolutionary value, some have argued that its ubiquity—major depression has a past-year prevalence of about seven percent of American adults—suggests some evolutionary benefits.

It’s important to remember, though, that evolution has allowed the continuance of other states which seem less likely to be helpful for survival, such as psychopathy. On the one hand, it is possible that psychopathy persists because it is relatively rare, with a prevalence of less than one percent ("frequency-dependent selection"), but this is hardly the case for depression. On the other hand, one explanation which has been applied to psychopathy is that it could result from such a large number of mutations that any single one is less likely to be under evolutionary pressure; this could be applied to depression, in which genomic studies have found that as many as 102 independent variants and 269 genes (6) may play a role. It is difficult, then, for natural selection to eliminate a trait with such complex origins.

Even if depression is associated with greater adaptivity, it may be that it is not depression per se, but some other unknown trait to which it is genetically linked, that has positive value. Or it could be that depression had some value in a past age or some specific situation that is now less applicable, and in that sense is similar to sickle cell disease in modern Western society. All in all, it should not be a foregone conclusion that the ubiquity of depression means that it has been favored by evolution.

In the next post in this two-part series, we will look at aspects of depression that have been claimed to be helpful—ruminations leading to problem-solving, and "depressive realism."

Portions of this post are adapted from Molecules, Madness, and Malaria: How Victorian Dyes Evolved Into Modern Medicines for Mental Illness and Infectious Disease.

References

1. Shenk, J.W.: Lincoln’s great depression. The Atlantic, October 2005. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2005/10/lincolns-great-depression/304247/ Accessed 2/28/21.

2. The Famous People: Enlightening quotes by Aristotle. https://quotes.thefamouspeople.com/aristotle-116.php Accessed 2/28/21.

3. Andreasen, N.C.: Creativity and mental illness: prevalence rates in writers and their first-degree relatives. Am. J. Psychiat. 144: 1288-1292, 1987. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3499088/ Accessed 2/28/21.

4. Pavrita, K.S. et al.: Creativity and mental health: a profile of writers and musicians. Indian. J. Psychiat. 49: 34-43, 2007. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2899997/ Accessed 2/28/21.

5. Ivcevic, Z., Grossman, E., & Ranjan, A. (2020). Patterns of psychological vulnerabilities and resources in artists and nonartists. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000309 Accessed 3/2/21.

6. Howard, D.M. et al.: Genome—wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat. Neurosci. 22: 343-352, 2019. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30718901/