Suicide

Suicide: Myths, Mental Illness, and Morality

Part 3: Talking suicide with psychiatrist and suicidologist Dr. Tyler Black.

Posted January 3, 2022 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Much of what we're taught about suicide constitutes a kind of "othering" that misleadingly separates ourselves from those at risk.

- The common teaching that older white men are at the greatest risk of suicide neglects substantial risks among other age and ethnic groups.

- Many people who die by suicide do not show "warning signs" and do not have significant mental illness.

- Suicide prevention programs should focus on normalizing feeling overwhelmed with life and reaching out for help.

This is part 3 of a dialogue about suicide with Dr. Tyler Black, a child and adolescent psychiatrist, suicidologist, and clinical assistant professor at the University of British Columbia. In parts 1 and 2, we talked about suicide rates during the pandemic, suicide risk assessment, and prevention. In this final installment, we'll wrap up by discussing myths related to suicide.

Joe Pierre: When we think about suicide as psychiatrists, we often think about treating mental illness as a key prevention strategy. But I’ve seen inconsistent claims about how many people who die by suicide are actually mentally ill. The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention cites CDC data to make the claim that 90 percent of those who die by suicide had a diagnosable mental health condition at the time of their death. However, a data brief by the CDC in 2018 reported that more than half (54 percent) of people who died by suicide did not have a known mental health condition.

It seems like the message has been that the discrepancy involves whether or not a mental health condition was appropriately detected (e.g. suggesting that an appropriate diagnosis is missed in many cases), but I also wonder about the distinction between formal mental disorders and less than perfect mental health. In other words, it’s hard to make the case that someone who dies by suicide was mentally healthy, but that doesn’t mean that they necessarily had a condition like major depression. I often use the phrase “not mentally healthy, but not mentally ill” to describe what we know about mass shooters, some of whom end up taking their own lives. To what extent does the same apply to suicide?

Tyler Black: Probably one of my most important myths to bust about suicide is the pervasive "90 percent" number you cited. This comes from horribly unscientific studies known as "psychological autopsies." It has been shown quite clearly that blinding the investigator, shortening the period of time between death and investigation, and randomizing accident vs. suicide investigation reduces this number significantly. This is a harmful advocacy piece and the AFSP should be ashamed for promoting it. If we want to get technical and say that someone dying from suicide has an "adjustment disorder" (or "specific phobia"… not kidding, this is one of the diagnoses in a PA study), then we should be very clear about what these disorders are and what they aren't.

I work with people who survived loved ones, acquaintances, coworkers, and classmates who die by suicide. This particular piece of advocacy creates so much needless guilt. Many people who die by suicide show no warning signs, and if they were to spend as many hours as necessary with a mental health professional prior to their death, there would be no signal of their upcoming death. I really hope that this myth can die, and that supposed "advocacy foundations" can stop harming people with it.

JP: There are a number of articles out there that address myths related to suicide. Are there any suicide myths that you’d like to dispel?

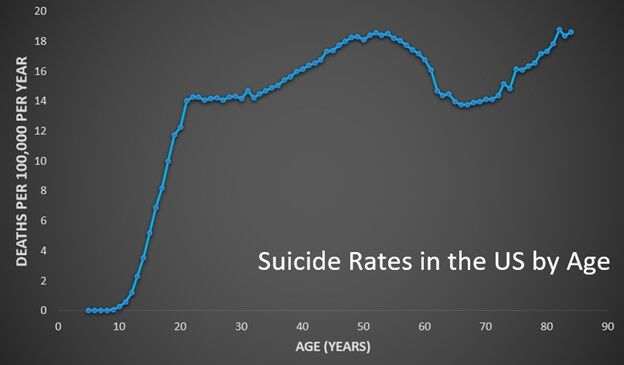

TB: Given that one of the first things almost every medical student tells me when I ask them about kids and suicide is that "kids and elderly are at higher risk for suicide"—the mythical "bimodal distribution." In truth, the age distribution of suicide looks like this:

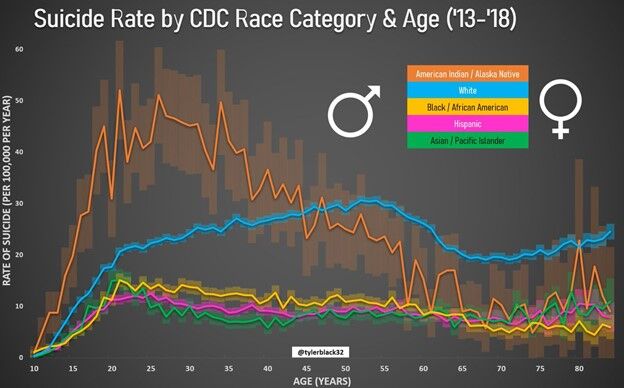

American advocacy groups are also woefully silent about the suicide rates of Indigenous people. I will commonly see claims that "white men" are most likely to die of suicide. But by population rate, this is easily demonstrated to be Indigenous people, and I really wish major suicide organizations in the United States would take Indigenous suicide seriously.

JP: A few years ago, I wrote a paper about culturally-sanctioned suicide. On the one hand, there is considerable moral condemnation surrounding suicide and we often talk about suicide as one of the worst possible outcomes we encounter as psychiatrists. But on the other hand, Western society is moving increasingly towards wider cultural sanctioning of suicide in certain circumstances—such as in the case of “physician-assisted suicide” in the setting of terminal illness.

What thoughts do you have about how people draw the line between when suicide is morally or ethically acceptable and what concerns should we have about how increasing public acceptance of suicide in some circumstances might impact suicide for conditions are situations that aren’t so hopeless?

TB: We all have a limit, and though I love my life and have no current suicidality, if I was given a terminal diagnosis with increasing suffering or about to burn alive in a building, suicide may be a better option for me. People do a grave disservice by "othering" suicide. We are all at risk for suicide due to various factors in our lives. Even without the extremes above, my risk increases if my wife leaves me or my job is threatened. Acceptance has to come first with the humility that our morality doesn't really matter to the suicidal person.

I try to keep my focus not on preventing every suicide, but on working to reduce distress, improve protection, improve connections, and improve quality of life. I know that by doing this, I am preventing unnecessary (not all) deaths. Psychiatrists are slow to accept this, but in medicine, an important lesson early is that everyone dies. I want people's lives to be of quality, dignity, and personal value. If someone out there needs something and that's the difference between wanting to live or die, I want to find a way to get it for them. If I can't reduce their distress or help their quality of life in any way, what am I doing except imposing my morality on them?

JP: In my experience, hopelessness—the premise that things will never get better—is often a cognitive distortion that lies at the root of suicidal thinking. Besides encouraging people to reach out for help through the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline number (1-800-273-TALK), how do you think we can all work to destigmatize suicidal ideation, encourage people to get help from a mental health professional, and spread the message that while things may feel terrible in the moment, there’s reason to be hopeful that things will change for the better?

TB: I think the more we take people in positions of respect and show their struggles (dispelling the "hero" vs. "coward" myth around suicide), we will help a lot of people. I think celebrities, athletes, doctors (c'mon physicians, why do we model such poor self/mental health care?!?!), and governments should work harder to make people understand that feeling overwhelmed is OK, and that help can reduce that feeling of being overwhelmed.

I wish we would do a little bit less "let's talk about it" and more "let's actually help." The national cancer research/prevention budget is about $6.5 billion per year in the U.S., and its suicide prevention budget is somewhere in the neighborhood of $40-100 million per year. It's simply not enough. We have to get past the "let's create a tool to identify at-risk people" stage and the "let's deploy protections and programs and assess their impact" phase, and that will require huge national projects. But, it's possible! Suicide rates have decreased by 40 percent in Japan over the past 15 years through national campaigns and efforts.

JP: Right, there’s no reason we can’t replicate that success here, but getting there will require changing some of the fundamental ways we think about suicide.

To read Parts 1 and 2 of this interview: