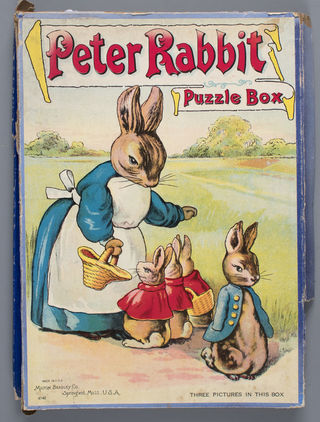

Once upon a time, at the tail end of a week that had lengthened with long commutes and sagged under the weight of deadlines, I snuggled in to read a storybook—a prim, well-loved, late-Victorian cautionary tale—with my older daughter, then not yet two years old. Readers will recognize the story’s rural setting and its familiar drama as farmer McGregor tries to protect his vegetable garden from a family of hungry humanized rabbits, one of them especially mischievous.

“Once upon a time,” I began to read the familiar beginning, “there were four little rabbits, and their names were Flopsy, Mopsy, Cottontail, and Peter.” Readers may remember what followed; the fretful warning against being put in a pie and eaten, the inevitable capture and perilous escape, the shining example of the disobedient bunny’s prudent sisters. That week these exciting twists weren’t enough to keep my eyelids from drooping, however. I began to drift as Farmer McGregor, who was planting young cabbages, waved a rake at the thieving bunny. “And Peter was…,” I tried to continue, but trailed off. A tug at my collar brought me back to the book. “And Peter was” I began, but again started to float away. Then a tiny, piping voice prompted me to go on, “And Peter was most dreadfully frightened!”

I learned two things from the experience. The first and most obvious, that the little listener had the text word for word, in mind and by heart. Remarkable as this sounds, the talent is yet not even slightly unusual. Linguist Stephen Pinker describes children as “lexical vacuum cleaners” for the way they powerfully suck up words. Toddlers add a new word to their lifelong dictionary every two hours. The acquisition rate is so rapid that by the time children are six, they will know about thirteen thousand words, Pinker says, and they accomplish this feat “despite those dull, dull, Dick and Jane reading primers which are based on ridiculously lowball estimates.”

And the second thing I learned is that children learn language mostly through play. The talent for hearing rhythm and appreciating prosody is an inborn human trait. But learning language itself, a unique feat of intellectual strength among all of our other fellow creatures, is for us humans mostly a process of playful experimentation and mimicry. I had confirmation of this about a year later, when visiting a crowded video store to rent a movie to pop in the videocassette recorder. (Many will remember renting movies and programs this way, fewer will recall VCRs.) As we moved through the music section I asked in a stagy voice, “Who’s your favorite tenor?” She enjoyed listening to the singing of a very large perspiring man dressed in black and white. “Luciano Pavaroti!,” she cried out in that same cheerful piercing voice. I risked another question, “And who’s your favorite principle dancer?” “Mikhail Baryshnikov!” she yelled. “Now you’re just showing off, kiddo…”

Her answer naturally drew stares from the shoppers, but it should have been no more amazing in those days than the common kids’ mastery of the multisyllabic names of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles or being able to name, as they easily could, the hundreds in the modern pantheon of superheroes.

Story reading is play. And so is storytelling. Both feed curiosity and feed on curiosity. Listening to stories tunes the ear and trains attention. As our daughters grew older they asked for original stories. One of these—a journey that began in our own neighborhood with a cab ride to the airport, proceeded by plane and boat, then rail and jitney bus, and then grandly on the back of a jolly, talking elephant—ended with an audience with the magnificent Maharajah of Rajhanapour whose kingdom nestled vaguely in the high Hindu Kush.

These stories, that began simply, elaborated to become a series. Splendid as was his realm, the travelers discovered that the Maharajah had not learned to read, and so, learning to read themselves, with the help of the Maharani, they taught the high king who had been too proud to take instruction. He went on to found one of the world’s great libraries, as it happened, and the kingdom became a celebrated center of learning and a magnet for cosmopolitan scholars.

In his younger days, the future Maharajah, a captain of the dashing lancers, was also a kind of sleuth, deducing that what had seemed like blood that appeared miraculously every fall, was instead a fermented liquid that seeped in seasonally from a pile of wet red leaves. He discovered that a charismatic blue demon, who had caught the attention of the populace and challenged the order of things, was instead a humble dye-maker dyed indigo in the course of his trade. (The crowd eventually turned on the imposter, and the story did not end at all happily for him.)

Whenever I’d run out of bedtime story ideas I’d resort to recycling plots to old comedies. One involved three penguins named (sorry…) Larry, Moe, and Curly. They would visit Niagara Falls, where Curly met the mean man who had stolen his girl. Infuriated, he could be calmed only with snacks; for an ending we’d chant “Moe, Larry, cheese! Moe, Larry, cheese!”

But usually, the main series stories would germinate with curiosity and then elaborate under questioning. Storytelling is one of the best ways to talk to young children, even when we are at a loss for words. Children always want to know what comes next. One thing will lead to another. The Tale of Peter Rabbit, in fact began eight years before as an illustrated letter that Beatrix Potter sent to Noel, the five-year old son of her former governess. “I didn’t know what to write,” the author and illustrator wrote, “so I decided to tell you a story about four little rabbits whose names were…”