Personality

Philosophy, Phrenology, and Introversion: From Kant to Jung

The Phlegmatic Roots of Schizoid and Avoidant Personality Disorders

Posted October 24, 2019

Kant’s Theory of Human Temperament

At the turn of the 18th century, Kant (1724 – 1804) reworked the Hippocratic-Galen theory and focused his analysis explicitly on describing the personality characteristics associated with the respective humours (Roback, 1928; see also Berrios, 1993; Merenda, 1987; and Stelmack & Stalikas, 1990). Kant (trans. 1978, p. 200) defined the phlegmatic type of individual as “cold-blooded,” apathetic, and rarely expressive of any signs of aggression. Kant also described both positive and negative manifestations of this temperament, highlighting idleness and lethargy on the one hand as compared to stoicism and emotional stability on the other.

Certain features that Kant (trans. 1978, p. 200) identified with the phlegmatic temperament—lack of anger expression and apathy—are still associated with modern day schizoid PD—but not avoidant PD—as defined in the DSM-IV (APA, 1994).

Jungian Literary Characterology

As opposed to the medical-based approach, literary characterologicals continued in the tradition of describing prototypical personality styles in narrative/story-like form (see Roback, 1928, for a review). Roback (1928) held that psychoanalytic theoretical conceptualizations of isolated, withdrawn, and detached individuals have their basis in the work of influential literary characterologists such as La Bruyere (1645 – 1696).

Roback reported that Jung’s concept of the introverted personality, a forerunner to current schizoid PD and/or avoidant PD, matched perfectly with one of La Bruyere’s characters. Consider La Bruyere’s description of a character named Phedon:

He is... .dreamy...thinks he is a nuisance to those he speaks...He is...timid...walks gently...afraid...with lowered eyes and dares not raise them to the passers-by. He is never among those who form a circle for discussion; he places himself behind the person who is speaking...and goes away if he is looked at...he walks with hunched shoulders, his hat pulled over his eyes so as not to be seen; he shrinks and hides himself in his cloak...(La Bruyere as cited in Roback, 1928, pp. 35 - 36).

In essence, La Bruyere described an extremely shy person from which one can easily recognize the features of schizoid personality as it is understood from a psychoanalytic as well as pre-DSM-III descriptive psychiatry perspective: Phedon is a quiet, withdrawn, loner who avoids social interaction in the context of what appears to be fearfulness, shame, and low self-esteem as well as day-dreaming tendencies (see Roback, 1928, for a related discussion). (In the DSM-III and DSM-IV, Phedon better matches the avoidant personality disorder category; cf. DSM-III, APA, 1980; also see Millon, 1981.)

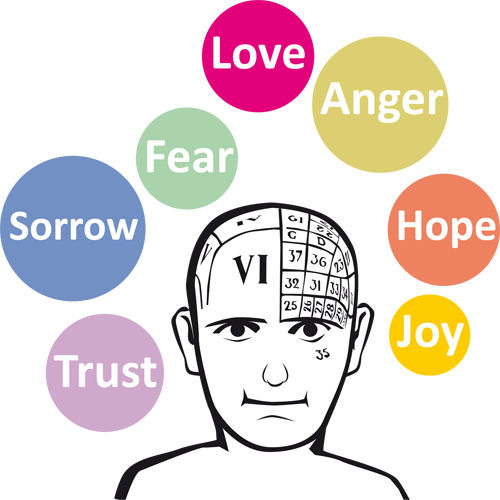

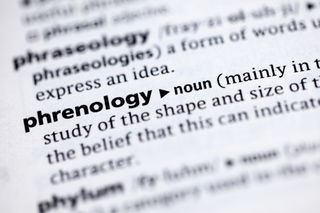

Phrenology and Faculty Psychology

Towards the end of the 18th century, influenced by the popularity of empiricism and faculty psychology, phrenology gained increasing respect (Berrios, 1993; Millon, 1981). As noted by Berrios (1993), Alexander Bain published a comprehensive account of the phrenological perspective in his work entitled, On The Study Of Character: Including An Estimate Of Phrenology (see also Roback, 1928, for a review). In this book, Bain (1861, p. 68) conceptualized the enjoyment of social interaction on the one hand, and the preference for solitude on the other, as two opposing psychological dispositions, comprising a bipolar dimension labeled sociability that was thought to be influenced by individual motivational factors.

In addition to his emphasis on the role of motivation, Bain (1861, pp. 237 – 238) also described emotionally cold types of people as individuals who lack the capacity for warm, caring feelings for others and cannot experience love due to an innate depletion. Bain’s notion of innately cold and emotionless individuals paralleled future descriptions of the “deficit” nature of these individuals (e.g., Millon, 1981). In the early 20th century, personality subtypes were increasingly described in the context of mental illness (for overviews, see e.g., Berrios, 1993; Maher & Maher, 1990).

References

Roback, A.G. (1928). The psychology of character: With a survey of temperament. New York: Hartcourt, Brass, & Company Inc.