Loneliness

Is Loneliness Killing Men?

Following 4 principles could help men make new connections.

Posted May 4, 2023 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- For decades, there has been a growing loneliness crisis.

- Friendlessness has contributed to despair and the risk of suicide, most commonly for males.

- Focusing on skill-building of the four factors of friendship may offer help.

The U.S. Surgeon General has recently called our attention to a crisis of loneliness in America. In his statement, he identifies factors such as having very few good friends or colleagues in the workplace, the need for more robust public health, equity aspects, and the role of social media in our lives.

In the long-range view, it’s been a growing crisis for about 30 years. We all watched it happen, not connecting friendship directly as the most important factor associated with happiness.

It’s been said that “being alone is different from being lonely.” This means that in being alone, we may be comfortable in who we are and getting some “me” time. When ready, we’ll return to social connection and the goodness of friendship.

Being lonely implies something additional and more fundamentally destructive within the loneliness than being physically solitary.

That factor that transforms pleasant aloneness into loneliness is despair. The Oxford Dictionary defines despair as “the complete loss or absence of hope.” In the "loneliness crisis," we ought to become curious about the causes of despair because it is a far greater concern than being pleasantly alone or somewhat lonely.

It is the elephant in the room of loneliness: “deaths of despair” and suicide. Death by suicide should be our deepest concern about the outcome of prolonged loneliness. The Surgeon General didn’t happen to mention that 78 percent of completed suicides in the United States are males.

I wish he did because, for the ever-expanding numbers of lonely men who come into my office, ten times more must be out there in the community, not even looking for help. Surveys are showing a marked drop in the size of men's social circles.

Within loneliness is friendlessness, and from loneliness, we often descend into the hopelessness of despair.

“Hopelessness about what?” one may ask. For nearly all the males that I see with loneliness and depression, there are only two general categories: the absence of romantic love and the absence of meaningful work. Clearly, the “at-risk” group the Surgeon General could be looking at are males of all backgrounds (although teen males and middle-aged males are most concerning).

The purpose of addressing loneliness is not for its own sake but ultimately and obviously to prevent the deaths it may cause. New programs exist to prevent depression in males that treat the root factors of male suicide. Some of the most prominent researchers in this area are Dr. John Barry and Dr. Martin Seager at the British Psychological Society.

Friendlessness Precedes and Predicts Loneliness

Not long ago, a large research study—The Harvard Study of Adult Development—identified the most significant non-clinical factor affecting mood problems such as depression and anxiety: friendship.

If we are concerned with the connection between loneliness and depression, then we ought to take a clue from the study showing that friendship mitigates depression.

Clearly, friendlessness precedes loneliness and all the tormented experiences of isolation that emanate from it.

We need a lens to look through to see the real causes and answers to the crisis. That lens is called the Biopsychosocial Model of medicine and behavioral health.

The Biopsychosocial Model

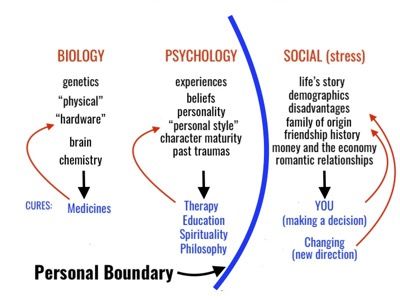

There are three general contributors to behavior, moods, and our problems: the biological, the psychological, and the sociological.

What is often not described in this model—if one doesn’t make it a diagram—is that there is a major, healthy barrier between our psychology and the sociology we are surrounded by: the personal boundary.

While the surgeon general’s intentions are beneficent, his toolbox relies on public policy and, inherently, in sociological, public policy solutions outside an individual's personal psychological mechanics. This personal boundary means that the only answer to the inner problem of loneliness and friendlessness also may only be found within a person and through actions the individual takes to correct it.

It would be beneficial for us to go back in history to study philosophers such as Aristotle on the anatomy of friendship, how we experience it, and what elements constitute it psychologically.

A Definition of Friendship

One might be hard-pressed to find a definitive source of knowledge on friendship and its psychological workings. Even the area of thought predating the modern sciences—philosophy—can be scanty on the subject.

One exhaustive source, however, is in The Nicomachean Ethics by Aristotle. In it, he posits different kinds of friendships and their workings. He says:

"With true friendship, friends love each other for their own sake and wish for each other good things."

This kind of friendship is only possible between “good people similar in virtue” because only good people can love another person for that person's own sake.

Nicomachean Ethics distinguishes three kinds of friendship: friendships of pleasure, of utility, and of virtue. The first is about self-gratification that happens to coexist with that of another person. The second is about mutual benefits that occur surrounding outer goals. The third is a friendship emerging from the maturity of character, optimizing collaboration and committed partnership.

The third is also supported by the modern models and theories of the likes of George Vaillant and his extensive work with ego defenses, his work in the Harvard Study of Adult Development, and the whole expanding new school of psychology by Martin Seligman called positive psychology. There are two concepts derived from evolutionary psychology that are useful in this regard:

- "We like those who like us"—the principle of reciprocal altruism; you scratch my back, and I’ll scratch yours.

- "We like those who are like us"—how we assort into social groups that offer the protections of “power in numbers” and familial-like loyalty to the group.

If we combine the good boundaries of mature character with these other views of friendship, we may arrive at the following:

Friendship = Consistent, Mutual, Shared, Positive Emotion

If you were to solve the “friendship crisis,” at least for yourself, you’d work on these four in yourself and look to find all four in others.

Evaluation and Improvement of Friendship

Consistency comes from working on and having a good boundary. This means your word is good, you are reliable and consistent, and you can be counted on even if it takes self-discipline to follow through on your promises. Yes, even if you feel exhausted and sad. Your friend will be all the more empathic toward your sadness and exhaustion because your "consistency" has a proven track record.

Mutuality is the fairness of the friendship investment and rewards for both people—being a “we” instead of a “me.” This factor satisfies the reciprocal altruism of “I’ll scratch your back if you scratch mine” or “liking those who like us back.” Yet, the personal boundaries of consistency raise this kind of "liking" to a higher level, akin to Aristotle's "friendship of virtue."

For example (from "Seinfeld"), if someone helps you move apartments, you someday owe them help with their own move. Even if you’re sad and lack energy, try to find something to give back from whatever you do have available. No matter how small, it will satisfy other friends with "mutuality."

Sharing fosters an emotional bond between two people through coordinated effort toward a goal or toward fun. It is the spirit of “liking those who are like us,” a sameness of background, beliefs, interests, and goals that only the in-person presence fosters as strongly. The personal boundaries of consistency again raise this other kind of "liking" higher, to Aristotle's "friendship of virtue."

Even if you don’t have much happiness to share or interests in common, maybe start small. Just share space with others by reading a book at the coffee shop or taking yourself out for a great dinner for one. Soon, you'll see the same people regularly, and that's a chance to introduce yourself based on your "shared" enjoyment of the venue.

Positive emotion is the fourth factor and definitive of friendship. The more we make people happy, the more valuable we are to them. The less we make them happy, the less valuable we are to them.

Friends aren't just happy people we know. They intentionally raise each other’s self-esteem. The consistency, mutuality, and sharing you've already cultivated form a perfect environment where positive emotion is taken in, transformed, and held onto as what can now be called self-esteem.

So what if yours is low?

Others who have an abundance of happiness just can’t help sharing the excess, and you should place yourself near people with high self-esteem inside, and positive emotion to give.

Others with an abundance of positivity pass it on to you while you only give a little back. That's okay. A back-and-forth of "positive emotion" has begun, and your slight grin at their jokes will soon release the first genuine laughter you've let out in a long time.

If you work on the four friendship factors, you could see your friendship circle grow and you with it. It could be your contribution and solution to the “friendship crisis” and a shield against your own loneliness, never to encounter despair. You’ll feel what the ancient philosophers called eudaimonia, or consistently “in good spirits.”

Facebook/LinkedIn image: Nenad Cavoski/Shutterstock

References

Seager, M. and Barry, J. (2014.) Gender-Related Schemas and Suicidality: Validation of the Male and Female Traditional Gender Scripts Questionnaires. Psychology.

Harvard Study of Adult Development. adultdevelopmentstudy.org

Vaillant, G. (2011.) Involuntary coping mechanisms: a psychodynamic perspective. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience.

Cox, D. (2021.) Men’s Social Circles are Shrinking. Survey Center on American Life.

Aristotle, The Nicomachean Ethics

Mruk, C. J. (2006). Defining Self-Esteem: An Often Overlooked Issue with Crucial Implications. Psychology Press.