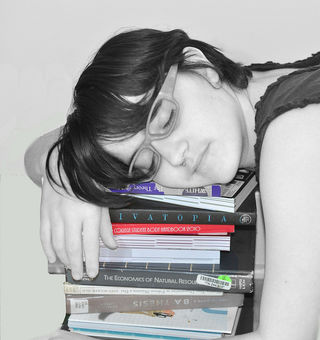

Sleep

The Secret to Getting A’s? Getting More Z’s

Three ways to help college students get the sleep they very much need.

Posted September 5, 2018

College students, like most of us, don’t get enough sleep. While college is stereotyped as a never-ending cycle of all-night cram sessions and dawn-breaking ragers, more often our students are sleep deprived from taking care of sick kids or working a double shift. Even more heartbreaking is when our students are sleeping in shelters, cars, or other venues not at all conducive to restful nights. And when students are tired, no matter the reason, learning is hard. Sleep deprivation inhibits both attention and memory formation, deficits that no amount of caffeine is going to fix. In fact, a survey of 185 undergraduates at a four-year university showed that sleep habits were a better predictor of first-semester GPA than diet, exercise, social support, religious habits, and emotional problems.

Although most sleep interventions cannot remedy the root causes of students’ sleep deprivation, they can help students make the most of the sleep time that they do have. Here are three types of sleep interventions that you should consider when trying to help your students achieve better rest and cognitive functioning.

The ABC’s of ZZZ’s

Just as we can teach success skills, such as learning strategies and time management, to college students, we can teach students how to sleep. Known formally as sleep hygiene training, these interventions typically involve an in-person presentation and handouts that dispel misconceptions about sleep and encourage better habits, including:

- No caffeine within 6 hours of going to bed.

- No late evening alcohol.

- All naps should last less than 1 hour, and no late afternoon or evening napping.

- No reading, texting, watching TV, playing video games, etc., in bed.

- Don’t go to bed hungry.

- Engage in moderate exercise during the day, but not close to bedtime.

- Go to sleep and wake up at consistent times each day.

The Sleep Treatment and Education Program for Students (STEPS) delivered this information to 82 undergraduates in introductory psychology. Six weeks later, students in STEPS took fewer naps, were less hungry at bedtime, and consumed fewer caffeinated medicines than students who listened to a 30-minute presentation on the scientific method. As a result, students in STEPS reported fewer sleep disturbances and shorter times between going to bed and falling asleep (i.e., sleep latency). A similar intervention known as Sleep 101 replicated some of these findings. In this case, a 90-minute program plus handouts corrected students’ maladaptive beliefs about sleep and significantly reduced their sleep latency.

Turning e-mail into ZZZ-mail

Another approach to improving college students’ sleep is to intervene over e-mail, text messaging, or social media. These methods allow you to scale an intervention to far more students than an in-person session, and to interact with students multiple times over a longer period. One example is called Refresh, which sent eight weekly emails to students based on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for insomnia. Interestingly, the control group received Breathe, which comprised eight weekly emails on coping strategies, also based on CBT. This design set up a strict test of sleep hygiene training by comparing it to a theoretically similar and comparably valuable type of CBT. Not only did Refresh improve the sleep patterns of students who began the intervention as poor sleepers, it also reduced their depression scores, whereas Breathe failed to accomplish either.

Another unique way to use e-mail within a sleep hygiene intervention is to provide personalized feedback about students’ sleeping habits. Over 100 female undergraduates completed a one-week sleep diary before attending a one-hour presentation on sleep hygiene. The next day, students received individualized feedback on their sleep patterns (derived from their sleep diaries), including comparisons to students from prior studies. Over the course of the following week, these women had better sleep efficiency, less delayed bedtimes, shorter sleep latency by over 9 minutes, and they were sending and reading fewer text messages in bed than they did during the week before the intervention.

Expressive writing

I’ve written in the past about the academic benefits of writing about one’s fears and anxieties before a big exam. This style of expressive writing has numerous other health benefits, one of which is better sleep. In one study, 96 undergraduates were randomly assigned to write a letter to either someone who supported them in the past, someone who had hurt or upset them in the past, or a school official arguing for or against a change in campus housing policy. Students who wrote either personal letter averaged a half-hour more sleep per night over the next month and reported better sleep quality compared to students who wrote to the school official.

In another experiment, 111 female students in introductory psychology courses were recruited into a study about body image and eating disorders. Across three sessions, these women wrote about their feelings toward their bodies and their own eating behavior, as well as how to use this reflection to improve any negative thoughts they had about their bodies. Women in the control condition wrote about how busy they were and how to use better time management skills. The expressive writing intervention showed little effect on women’s body image or disordered eating behavior, but did significantly reduce sleep disturbances.

Sleep, from A to ZZZ

Although many students are too busy to sleep for an adequate number of hours, these studies provide multiple ideas for how to help students improve the sleep that they do get. Simply providing information about good sleep hygiene could go a long way because many students have misinformed lay theories about sleep and don’t realize that they could be sleeping better. Checking in with students about their sleep behaviors via e-mail, text, or social media could bolster these effects by reminding students about sleep hygiene and providing a casual nudge to put those lessons into practice. Finally, advising students to write down their negative feelings in a journal or diary could help them set aside their daily worries before they drift off to a more restful slumber.

References

Arigo, D., & Smyth, J. M. (2012). The benefits of expressive writing on sleep difficulty and appearance concerns for college women. Psychology & Health, 27(2), 210-226.

Brown, F. C., Buboltz, W. C., & Soper, B. (2006). Development and evaluation of the Sleep Treatment and Education Program for Students (STEPS). Journal of American College Health, 54(4), 231-237.

Kloss, J. D., Nash, C. O., Walsh, C. M., Culnan, E., Horsey, S., & Sexton-Radek, K. (2016). A “Sleep 101” program for college students improves sleep hygiene knowledge and reduces maladaptive beliefs about sleep. Behavioral Medicine, 42, 48-56.

Levenson, J. C., Miller, E., Hafer, B., Reidell, M. F., Buysse, D. J., & Franzen, P. L. (2016). Pilot study of a sleep health promotion program for college students. Sleep Health, 2(2), 167-174.

Mosher, C. E., & Danoff-Burg, S. (2006). Health effects of expressive letter writing. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 25(10), 1122-1139.

Trockel, M. T., Barnes, M. D., & Egget, D. L. (2000). Health-related variables and academic performance among first-year college students: Implications for sleep and other behaviors. Journal of American College Health, 49, 125-131.

Trockel, M. T., Manber, R., Chang, V., Thurston, A., & Tailor, C. B. (2011). An e-mail delivered CBT for sleep-health program for college students: Effects on sleep quality and depression symptoms. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 7(3), 276-281.