Environment

Nudges in the Wild: Merely Exposing Children to College

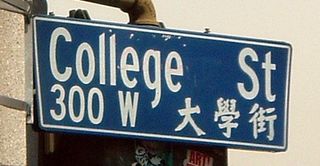

Street signs could change the way children think about going to college.

Posted June 6, 2017

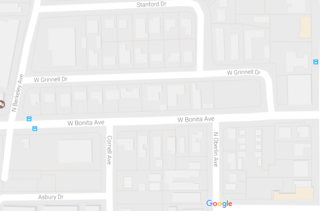

I imagine that children growing up in Claremont, California, have no shortage of knowledge about college options. Without leaving home they have the choice of five wonderful institutions right in their backyard, and some of their parents are likely connected to the Claremont Colleges in some way. But during a visit to Claremont’s Pitzer College, I noticed a subtle nudge that could have a profound impact on how the children in this community think about college. While strolling one evening from Pitzer to downtown Claremont, I noticed something about the streets I was crossing: Harvard Avenue, Oberlin Avenue, Dartmouth Avenue, Berkeley Avenue…If you look at a map of Claremont, it reads like the college rankings from U.S. News & World Report! I couldn’t help but to picture the conversations parents must have with their children when they ask, “Where’s Northwestern?” or “What’s a Cornell?”

But those street signs may have a more subconscious impact on children’s thinking about college. One of the most robust findings in psychology is the mere exposure effect, which is our tendency to feel positively toward novel stimuli after even subliminal exposure. In other words, we like something better if it’s even remotely familiar to us. Beginning in the late 1960s, Dr. Robert Zajonc showed that college students liked nonsense words and meaningless symbols better after repeated subliminal exposure. This led to his famous quote “preferences need no inferences,” meaning that people don’t need to consciously process or remember something in order to like or dislike it. These results extend to our social interactions: after subliminal exposure to a stranger’s photograph, college students were more likely to side with them in a disagreement between that person and another stranger. And, of course, mere exposure is a core process in influencing consumer choice, whether one is advertising a car, a political candidate, or even a college.

In fact, this mere exposure strategy is part of the ‘early college’ approach leveraged by a number of school districts both public and charter. Starting as early as elementary school, nudges in the environment encourage students to think about college and help to fortify their own expectations that they will one day matriculate. These nudges include naming classrooms and other student groupings after universities, hanging college pennants in the hallways, and staging university t-shirt days. These daily exposures lay the groundwork for more formal activities that provide students with information about attending college, such as research projects on universities and campus visits. But even as these nudges fade into the background, their presence will continue to instill in children the belief that they can and will attend college after they graduate from high school.

Whether or not the street names in Claremont were intended as a brilliant piece of social engineering, what an amazing nudge. Just imagine how a child thinks about college after spending their whole life living on Grinnell Drive or having attended school on Santa Clara Avenue. Not only is college something they might consider (even subliminally) every single day, but they’re also exposed to the notion that great colleges exist all across the country. Communities that want to get youth thinking about college can take inspiration from Claremont, even if renaming their streets proves infeasible. Not only could local schools adopt early college strategies, but libraries and community centers as well could hang college decorations and name youth-designated areas for universities. Youth sports teams, which are often named after professional clubs like the Yankees and Dodgers, could instead use college-related names like Spartans and Cougars. And community-wide events, like fairs or parades, could recruit involvement from local colleges and their students. Leveraging the mere exposure effect through these and other creative efforts could prove to be a low-cost, high-impact approach for encouraging children to aspire to a college degree.

References

Bornstein, R. F., Leone, D. R., & Galley, D. J. (1987). The generalizability of subliminal mere exposure effects: Influence of stimuli perceived without awareness on social behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(6), 1070-1079.

Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9(2), 1-27.