Gratitude

Sorrow at a Loss or Joy at a Life?

Why am I grateful for the life of my son, who killed himself twenty years ago?

Posted May 16, 2019 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

At the graveyard a few weeks ago my family observed the twentieth anniversary of my son’s suicide. As always when I think of Aaron, my sense of loss that day was mixed with my gratitude for the twenty good years we had with him, before the ten painful years of his schizophrenia, and his choice to end his pain forever.

My immediate reaction when I was told of Aaron’s death was shock and denial. But after that first moment, I didn’t feel surprise. I knew well the misery he had lived with. He had experienced his illness as a series of attacks and lies: people were putting poison in his food, they were insulting him out loud, they were lying to him. He never believed he had a mental illness. Instead he was convinced that the world and his parents were conspiring against him.

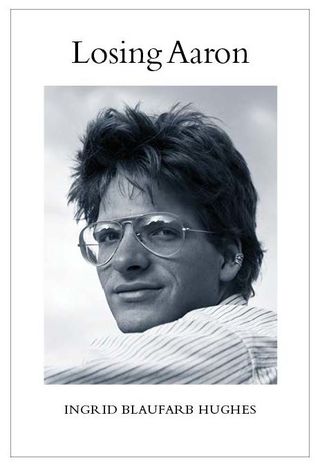

During the first months after his death, he was naturally on my mind a great deal. It was comforting to talk to friends and relatives about him, to reminisce about the good times and commiserate about the bad ones. In my journals I had extensive notes on our conversations over the years, but found it too wrenching to read them over, though I was able to look at the photographs his father or I had taken and his own self-portraits. Often I had insomnia. I might eventually fall asleep, helped by pills a doctor prescribed, only to wake from nightmares with a terror that thrummed through my body and gradually died back to lie in my gut. Though I was much more aware of suicides in the world around me, as time passed, I became less preoccupied with Aaron. But I found the thought of him would come to me as I approached the door to our house or got in to bed. It was years before I could write about him. (My book, Losing Aaron, is available from Amazon.)

On the other side of the scale, and far outweighing the sorrows, is the delight of life with Aaron. From elementary school, he was focused on math and science. At twelve, before home computers were commonly available, with no help from any adult, he put together a computer using our TV as a screen and a cassette tape for memory. He began cooking around the same time, making blintzes for one of his first family meals. By high school, he could explain his physics homework so clearly that his intelligence became yours. I loved sitting in the living room with him and hearing about his day: his teachers, his classmates, the work he was doing in English or shop or geometry. I loved watching him embroider an archipelago of patches onto his girlfriend Katherine’s jeans. One of my favorite stories about him is told by Katherine:

For a few weeks we had a health class teacher at Stuyvesant whose classes consisted of lecturing us, don’t smoke, don’t have sex, if you have sex you’ll get pregnant, that’s terrible. After listening for a week or two I got fed up and I yelled at him, “You don’t understand anything.” He said to see him after class. So after class in the hall, instead of looking at me, he was looking over my shoulder. I turned around and Aaron was standing behind me. He said, “I agree with her, and whatever you have to say to her you can say to me too.”

I shared Katherine’s feeling: Aaron had your back. His intelligence, his confidence, his kindness supported all of his family and friends. And in many ways it still does.