Neuroscience

Should I Pay My Son $100 to Quit Fortnite?

A neuroscience-based parent guide to your nightly battle royale fight.

Posted December 18, 2019 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

I spoke recently at the #EdCrunch education conference in Moscow on a panel called “A Child on the Internet: Prohibit, Observe, or Explain?” If you are wondering how scientists do research for a discussion about kids and gaming, I was surprised to see that three out of the four panelists, including me, asked their own kids to help with the answer. There’s no roadmap for it.

As a neurobiologist, my answer was that we do not Prohibit, Observe, nor Explain. None of those will work long-term. Instead, we need to engage with the process. We need to stay in charge by understanding not how the games work, but how the brain works.

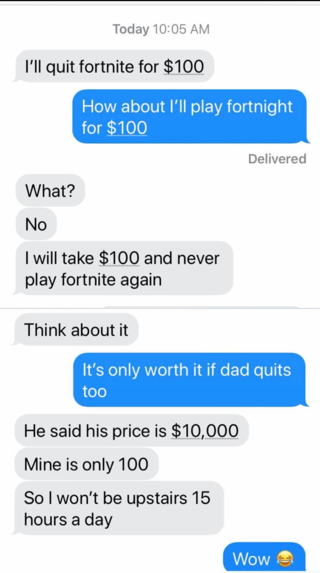

It’s a problem not just for the experts. My sister sent me this Fortnite text exchange from her son and wondered, “Should I actually pay him the $100? Is it worth it?”

These games are engaging virtual realities. They are experiential learning playgrounds that tap into everything our brain is primed for: Immediate reward, problem solving, constant feedback about how our progress is going, and importantly for our preteens and teens—social interaction. It’s the perfect storm for addictive behavior and parents have to handle it on a daily basis. We have battle hungry babies that need to be reined in.

Here’s my how-to Fortnite Battle Royale parent strategy:

- See that screen time is not actually the enemy. Yes, too much screen time is bad for our kids—not because staring at a screen is bad for their brain or eyes, but because TV and video games take up so much room in their lives when they should be having hands-on, face-to-face, real world experiences instead. It’s the things they are missing out on due to computer games that cause problems, not so much the games themselves. Limits make sense here.

- Understand these games are not benign. Parents won’t be surprised to know that playing violent video games can cause increased aggression for an entire day after the video game has been turned off, especially if the player keeps thinking about the game and ways to improve their play. Be careful about the types of games your kids play.

- Consider that massive multiplayer online games (MMOGs) are different than the games of your youth. A MMOG can’t easily fit into a one-hour screen time block a day. It is, by definition, a giant, open, persistent world, with both opportunity and high stakes play always waiting there in your living room. It calls to kids day and night like a bustling 24-hour Target waiting for the binge impulse shopper. You’re not alone in your struggle to control it: When a Fortnite mom screams at her child to get off for the 7th time because he’s kept on playing after his timer has gone off, remember that through the magic of MMOGs, our houses can hear what happens in your house, as our homes are virtually knit together through the audio of this reluctant parenting connection.

- Acknowledge that these games can provide an important social connection. Enforcing extreme limits on the time your child can game with their actual friends can prevent interactions that you actually want your child to have, especially in older kids. Real communities are built in these online worlds where there is overlap with between virtual and face-to-face relationships: Kids talk about the games in school the next day.

- Know your kids are not lazy. Playing video games is not a waste of time. Our kids are always learning and the brain is keeps developing in response. Kids are desperate to learn, happy to pursue a goal, delighted to have a social pack; they are so motivated to get better that they sneak out of bed at night and turn on the Xbox to work at getting their first Victory Royale. Massive online video games have raised the bar for kid engagement. These clever games are an indicator of change—It’s a virtual revolt against the way we’re trying to make kids learn things in school and, as such, they present a challenge to educators everywhere to make the learning worth doing, more interesting than video games.

- Exploit what we know about learning. As a neuroscientist, I started thinking about the mechanics of learning and how I could apply that knowledge to the Fortnite problem. Neuroscience has shown that repeated exposure to something with rest periods in between is the most effective way to learn something. Practice strengthens connections between neurons and makes that pathway stronger. So, what if your child is dying to do something that you’re not thrilled about? The ability to swiftly execute a headshot from afar so you’re the only survivor is not what I want my son practicing on a daily basis. Instead of daily video game playing time, be open to your child playing weekly in bigger chunks. Approach gaming time the opposite of the way you would have him study for a major exam. If your son studies for an algebra test for five hours the night before, he won’t learn it as well as if he studies an hour a day for five days in a row. So consider banking your child’s play time: Instead of an hour a day during the school week, he gets 5 hours in one chunk on the weekend.

- Use Fortnite as a tool. Fortnite is a huge opportunity for both kids and parents to allow children to set and stick to their own limits. It’s up to them to come up with reasonable limits and consequences for what happens if they can’t adhere to those limits. In other words, the child makes their own rules, and the parent agrees to them. Fortnite could be a way for kids to work on much-needed self-regulation skills. The struggle is not ours alone, so don’t shoulder all the responsibility for the structure of it. Let them make the rules, as long as you agree with those rules. You want your child to set up self-regulation skills that will eventually work when you’re not around to enforce them.

- Don’t turn down a good bribe. Bribes, or incentives, are a useful tool to foster the brain connections you want to keep: Would you give your child $100 to stop playing Fortnite? If Fortnite continues to be a problem in your house after the child has set their own rules and consequences and he comes up with idea himself, neuroscience says yes. Bribing is absolutely worth using to craft brain development at sensitive times. If practice strengthens pathways, then lack of practice does the opposite. When used, pathways grow functionally stronger. And once used, they’re more likely to be used again the next time. In this case, lack of use will make the unused connections wither away. It doesn’t have to be money—There are lots of ways to incentivize behavior. But be clear about what will replace Fortnite though—Your child should come up with a plan. And if you do bribe, you need to deliver!

As parents become more involved in our children’s digital usage, we can delay exposure, we can set limits, or we can control their apps with parental controls, but we won’t always be working on the same platforms they are, and we aren’t always familiar with the games they’re playing. It may be Fortnite now, but it will be something else next. We can use these tools to empower our kids and to cope not with specific games, but with any unknown online platforms that our children are enchanted with.

References

Brad J. Bushman and Bryan Gibson. "Violent video games cause an increase in aggression long after the game has been turned off." Social Psychological and Personality Science 2, no. 1 (2011): 29-32.

Jean Decety and Julie Grèzes, “The Power of Simulation: Imagining One’s Own and Other’s Behavior,” Brain Research 1079, no. 1 (2006): 4–14.

Laura Michaelson et al., “Delaying Gratification Depends on Social Trust,” Frontiers in Psychology 4 (2013): 355.

Brooke N. McNamara, David Z. Hambrick, and Frederick L. Oswald, “Deliberate Practice and Performance in Music, Games, Sports, Education, and Professions: A Meta-Analysis,” Psychological Science 25, no. 8 (2014): 1608–1618.