Education

Lessons Learned From Working With Young Children

Personal Perspective: Teach to natural strengths and encourage good habits.

Posted August 21, 2023 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Improvisation is second nature to many children.

- Children are often quick at spotting patterns.

- It’s never too early to teach children effective practice strategies.

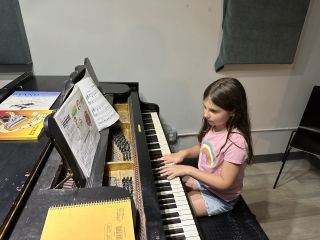

Young children love improvising.

In the visual domain, doodling is a human instinct from an early age. In the auditory domain, it is young children’s natural inclination to improvise tunes that they have heard from commercials, movies, and ambient music. Instead of “killing” the natural inclination, I found using improvisation, a preferred activity by children, to reinforce their less favorable activities, e.g., playing exactly as written in the score, works well in sustaining on-task behaviors.

This can be accomplished by persuading the child to do their best to play the piece exactly as written. As soon as the child has done that, I assure them that they have earned the status of a living composer and can now add whatever decorative notes (e.g., passing and neighboring tones, arpeggios, chords) they wish to shape the musical phrases by creating variations of the main melody, with the aim of making the piece more interesting than as written. In this instance, using more desirable activities (i.e., the freedom to improvise) to reinforce the less desirable activities (i.e., abiding by the rules of the printed notations) can help both the teacher and the student to reach the learning goals of the lesson, without stifling young children’s natural bent to improvise.

Children are good at pattern recognition.

Young children are often challenged by finding the keys that match the musical notations written on the score. Instead of using trial and error, I find that playing pattern recognition games (e.g., two-black-key sequences vs. three-black-key sequences) can be helpful in introducing the relative positions of various pitch classes on a keyboard. Many children spot patterns quickly, and some spontaneously extract insights from guided explorations. No sooner did the children discover that the two-black-key sequence is interleaved with the three-black-key sequence across the entire piano keyboard, with “Cs” and “Fs” residing in the leftmost segment of the two-black-key and three-black-key pattern, respectively, than they became efficient at finger placement across the entire keyboard, using Cs and Fs as their guideposts or reference notes.

Inculcating effective practice habits can start in childhood.

Mistakes exist in the gap between two notes. On the violin, things could go awry between two notes when there is a delay in bow placement, faulty articulation, or incorrect timing of the shift, among other issues. Many pedagogues advocate for isolating technical issues and tackling a single technical issue at a time. This approach is akin to scientific experimentation, where one independent variable is being manipulated at a time.

Based on my experience, it is not too early to introduce these practice tips when teaching children. These healthy practice habits, which include isolating tricky spots or error-prone passages and working outward from the identified problematic areas, often significantly cut down practice time and result in speedier progress. Most children are already practicing in bite-sized chunks, which makes isolating technical issues easy to implement across multiple practice sessions, especially under the supervision of supportive parents.