Anxiety

What Triggers Your Anxiety—Classic Old Threats or New Ones?

With so many distressing things around us, can we learn to worry selectively?

Posted June 18, 2019

How are spiders, snakes, and heights different from ionizing radiation, semi-automatic weapons, and chainsaws? The first ones are classified as ancestral threats because they have been around since the beginning of human history. The newer, sophisticated, beautiful, fast-paced, and sometimes dangerous world we inhabit now began about 10,000 years ago with the advent of agriculture. Modern threats—the second set of items above—belong to this more recent era.

Modern Threats

In addition to evolutionary threats (e.g., predators and diseases), modern humans encounter a staggering array of novel threats that did not exist until very recently on an evolutionary time scale. A modern threat is anything that poses a problem today but not in our ancestral past. While snakes, spiders, and other animals have been alarming since the begin of human history, today we must also be cautious of fast-moving automobile traffic, firearms, and razor blades. Additional modern threats to consider are automatic weapons, electricity, weaponized nanotechnology, pollution, fried foods, alcohol, drug overdoses, decompression, power drills, and helicopters.

Researchers have found that some of the threats present in our ancestral past (e.g., snakes and spiders) can induce stress responses to modern humans even at the very young age of six months (Hoehl, Hellmer, Johansson, & Gredebäck, 2017). It is not even necessary for humans today to have had negative experiences with the creatures to fear them. They are likely embedded in us thanks to our ancestors' coexistence with them for 40 to 60 million years. More modern threats include knives, airplanes, and syringes, but they have not been around long enough to establish a threat response from birth.

Natural selection molded mechanisms into our ancestors' brains that were specialized for focusing cognitive energy on humans and other animals. These adaptive traits were then passed on to us. Humans today are biased to pay attention to other people and animals much more so than non-living things, even if inanimate objects are the primary hazards for modern, urbanized populations (New, Cosmides, and Tooby, 2007).

Are we worrying about the wrong things?

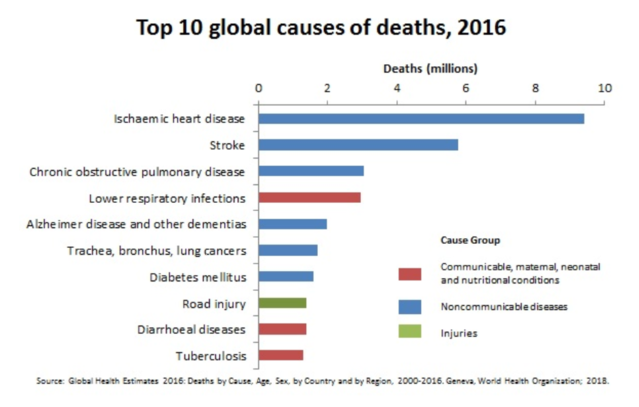

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the top causes of death globally are heart disease, stroke, pulmonary disease, respiratory disease, and Alzheimer’s and other dementias. Combined, these five issues are implicated in approximately 23 million deaths (World Health Organization, 2016). If the danger detectors in our brains were perfectly in tune with our current industrialized world, we would focus our attention on threats that have a greater chance of bringing us down. Statistically speaking, you are much more likely to die from heart disease in our modern world than jet engine failure or a lion attack. Yet we seem to be overly anxious about airplane crashes and the odd death-by-tiger story and less panicked by cardiac health and lung infections.

Ancestral Threats and Biological Preparedness

Throughout human evolution, the ability to identify threatening situations has been a critical feature of our psychological structure. A failure to recognize and thwart a threat could have been fatal for our ancestors much like it could be now. The concept of biological preparedness—a theory about the psychology of fear and our reactions to threats—argues that the successful identification of environmental threats leads to a reproductive and survival advantage for the individual (Seligman, 1971). In this view, children learn to fear some threats more quickly than others and, consequently, seem biologically prepared avoid poisonous animals but less prepared detect the difference between the sidewalk and street traffic.

The Environment of Evolutionary Adaptedness (EEA) is the ancestral environment to which a species is adapted, or the set of Darwinian natural selection pressures that shaped an adaptation. A central premise of evolutionary science is that forces in our distant past helped make us who we are today. The EEA refers to a group of selection pressures occurring during an adaptation’s period of evolution responsible for producing the adaptation (Tooby & Cosmides, 1992). A selection pressure can be any factor in a population that impacts reproductive success. Physical, social, and intrapersonal pressures from our ancestral past help to shape our current human design because all animals have heritable variations that are selectively favored or disfavored in accordance with reproductive success (Buss, 1995).

Conclusion

Nearly 75 percent of all deaths in the U.S. are attributed to just 10 causes, with the top three of these accounting for more than 50 percent of all deaths. So why are we afraid of so many things? Throughout human evolution, the ability to identify threatening situations has been a critical feature of our psychological structure. A failure to recognize and thwart a threat could have been fatal for our ancestors. In contrast, the primary threats to most people today, especially in modern urban settings, are different than the environmental threats dominant up until a few centuries ago. We now increasingly face threats that are substantively different, more technical, and in some ways less tangible.

References

Bennett, K. (2018). Teaching the Monty Hall dilemma to explore decision-making, probability, and regret in behavioral science classrooms. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 12 (2), 1-7.

Buss, D. M. (1995). Evolutionary psychology: A new paradigm for psychological science. Psychological Inquiry, 6, 1-30.

Hoehl, S., Hellmer, K., Johansson, M., & Gredebäck, G. (2017). Itsy bitsy spider…:Infants react with increased arousal to spiders and snakes. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1710. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01710

New, J., Cosmides, L., Tooby, J. (2007). Category-specific attention for animals reflects ancestral priorities, not expertise. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104(42): 16598–16603.

Seligman, M. E. P. (1971). Phobias and preparedness. Behav. Ther. 2, 307–320. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7894(71)80064-3

Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (1992). The psychological foundations of culture. In J. Barkow, L. Cosmides, & J. Tooby (Eds.), The adapted mind (pp. 19-136). New York: Oxford University Press.

World Health Organization (2016). The top 10 causes of death. Retrieved June 11, 2019, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-d….