Environment

The Coming Out Cycle

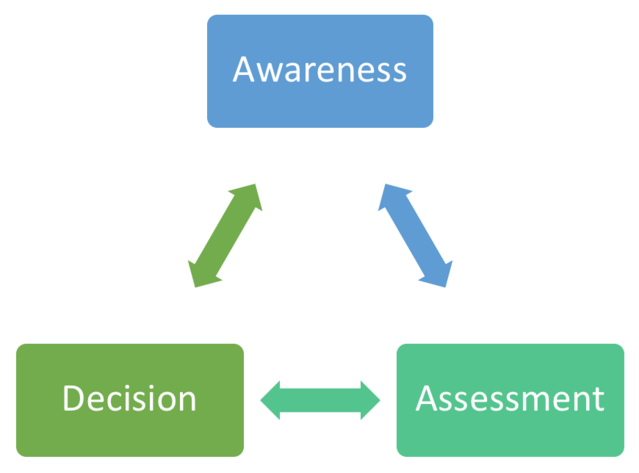

Why we need to recognize the cyclical nature of the coming out process.

Posted June 5, 2018 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Coming out is commonly conceptualized as a one-time experience. The stereotype is often of a young LGBTQ+ individual coming to terms with their own identity, achieving self-acceptance, and deciding to disclose to everyone in their lives.

In the best cases, they are met with love and acceptance, nowadays there may even be a party involved. This simplified view minimizes the complexity of coming out, which in reality is a series of coming out processes than encompass the lifespan.

LGBTQ+ individuals face a number of stressors when considering coming out. Although hopeful to be met with care and compassion, when considering coming out LGBTQ+ individuals are often plagued by the following questions:

Will ________ understand?

Will ________ still treat me the same way?

Will ________ judge me?

Will ________ be angry?

Will ________ be sad?

Will ________ hurt me?

Will I lose my job?

Will I lose my home?

Will I be safe?

Enduring these stressors, LGBTQ+ individuals often feel lonely, disconnected, confused, sad, ashamed, fearful, angry, and vulnerable. These coming out stressors help to explain the unfortunate statistic that LGBTQ+ individuals are 3 times more likely to experience a serious mental health concern.

Since individuals may react in a variety of ways spanning from acceptance to abuse, each disclosure process can be uniquely different. A process is seen as a means to an end, hence, in actuality, coming out is a set of processes. Further, it is important to reconsider coming out as a cyclical occurrence in order to better understand the minority stress that is endured with subsequent disclosures. Once an individual has disclosed to their loved ones, telling others may seem simple, however, that may not be the case. Although an individual may be "out and proud" for decades, due to individuality and context, an individual may have difficult coming out experiences throughout the lifespan. Common examples may include moving to a new neighborhood, blending families, or switching jobs. Regardless of an individual's self-acceptance, such moments may cause those questions, emotions, and stressors to reappear.

Awareness

The awareness phase begins the moment an individual is triggered to consider whether or not to disclose. For example, Alex told his parents he was gay 8 years ago. Since, he has slowly come out to the rest of his loved ones and has been with his partner for 4 years. However, Alex recently changed jobs and a coworker asks him if he’s in a relationship. Regardless of Alex’s self-assurance, love from his partner, and validation from his loved ones, he may experience the stressors of deciding whether or not to disclose to his coworker. Almost a decade later, Alex is in another coming out process.

Assessment

In the assessment phase, the individual thoroughly considers whether or not disclosure is needed and helpful. This could take as little as a few minutes in some cases, and months in others. Regardless of how long ago an individual first came out, due to variances in context it is still warranted to consider the intention and consequences surrounding the disclosure. It is helpful to consider if the disclosure is important to the client. Further, it can be practical to consider both the potential benefits and risks. Visibility can come with a price and is a valid choice, however, choosing to withhold can prompt feelings of anxiety, shame, and insincerity.

Decision

The decision phase is characterized by following through with either the decision to disclose or the decision that disclosure is unwarranted. Ideally, an individual feels empowered, whether or not coming out occurs in that instance. Further, reflection is helpful to acknowledge how the individual was affected by the decision. From each opportunity to come out an individual has the opportunity to experience coming out growth. Gains from this empowered recognition and stance could help to combat the stressors experienced throughout the process. Recognizing the cyclical nature of coming out, coming out growth experienced from the decision could help to buffer against future coming out stressors.

References

Ali, S. (2017). The coming out journey: A Phenomenological investigation of a lifelong process VISTAS.

Ali, S., & Barden, S.M. (2015). Considering the cycle of coming out: Sexual minority identity development. The Professional Counselor 5 (4). 501-515.

Association of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Issues in Counseling. (2013). Association for Lesbian,Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Issues in Counseling competencies for counseling with lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, questioning, intersex, and ally individuals. Alexandria, VA: Author.

Cass, V. C. (1984). Homosexuality identity formation: Testing a theoretical model. The Journal of Sex Research, 20, 143–167. doi:10.1080/00224498409551214

Cox, N., Dewaele, A., Van Houtte, M., & Vincke, J. (2011). Stress-related growth, coming out, and internalized homonegativity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. An examination of stress-related growth within the minority stress model. Journal of Homosexuality, 58, 117–137. doi:10.1080/00918369.2011.533631

Degges-White, S. E., & Myers, J. E. (2005). The adolescent lesbian identity formation model: Implications for counseling. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development, 44, 185–197.

doi:10.1002/j.2164-490X.2005.tb00030.x

Dermer, S. B., Smith, S. D., & Barto, K. K. (2010). Identifying and correctly labeling sexual prejudice,

discrimination, and oppression. Journal of Counseling & Development, 88, 325–331. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00029.x

Denes, A., & Afifi, T. D. (2014). Coming out again: Exploring GLBQ individuals’ communication with their parents after the first coming out. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 10(3), 298-325. doi:10.1080/1550428X.2013.838150

Dunlap, A. (2014). Coming-out narratives across generations. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 26,318–335. doi:10.1080/10538720.2014.924460

Floyd, F. J., & Stein, T. S. (2002). Sexual orientation identity formation among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: Multiple patterns of milestone experiences. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 12, 167–191. doi:10.1111/1532-7795.00030

Klein, K., Holtby, A., Cook, K., & Travers, R. (2015). Complicating the coming out narrative: becoming oneself in a heterosexist and cissexist world. Journal of Homosexuality, 62, 297–326. doi:10.1080/00918369.2014.970829

Kosciw, J.G., Greytak, E.A., Diaz, E.M., & Bartkiewicz, M.J. (2014). The 2013 national school climate survey: Experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth in our nation’s schools. New York: Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Educational Network

McCarn, S. R., & Fassinger, R. E. (1996). Revisioning sexual minority identity formation: A new model of lesbian identity and its implications for counseling and research. The Counseling Psychologist, 24,

Meyer, I. H. (2014). Minority stress and positive psychology: Convergences and divergences to understanding LGBT health. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(4), 348-349. doi:10.1037/sgd0000070

Riggle, E. D. B., Gonzalez, K. A., Rostosky, S. S., & Black, W. W. (2014). Cultivating positive LGBTQA identities: An intervention study with college students. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 8, 264–281. doi:10.1080/15538605.2014.933468

Vaughan, M. D., & Waehler, C. A. (2010). Coming out growth: Conceptualizing and measuring stress-related growth associated with coming out to others as a sexual minority. Journal of Adult Development, 17,