Addiction

Is Addiction a Disease?

Using the I-M Approach to explore addiction

Posted January 23, 2015

Is addiction a disease? Do the kids I work with at CASTLE have a pathological response to drugs and alcohol? The disease model of addiction is compelling, and has served its purpose in bringing needed attention of healthcare professions and legislators. My concern about the model is that it continues to stigmatize my patients, and the millions of people struggling with addictions, suggesting they are sick.

Many years ago we used the word invalid to describe people with illness, in particular a person who is incapacitated by a chronic infirmity or disability. Addiction is thought to be chronic, accounting for the potential lifelong vigilance against relapse. The model supports the idea that people who have addictions have a medical condition, and should not be blamed or seen as the modern pariahs and lepers of our society. Addiction is a disease, not a moral issue.

But the word invalid can also be broken down to its constituent parts; in-valid. “Invalid” is defined as flawed, illegal, without validity. This belies the very efforts made to validate my patients who struggle with addictions. It is the dark side of attributing the medical model of disease to the condition of addiction.

Like any disease, a person is held responsible perhaps not for the disease itself, but for the treatment of the condition. A diabetic may not be at fault for diabetes, but is held responsible for taking insulin, managing their blood sugar, being aware of their diet. Addiction is no different. Whether my patients are using heroin or alcohol or marijuana they are held accountable and responsible for their actions. Having a disease is not a tacit nod to enabling.

Dis-ease implies that the condition itself is a disruption of equilibrium, causing discomfort and recruiting the rest of the body to respond to this discomfort. The risk is that the disease model itself becomes the crutch, perpetuating the myth of a crippled and in-valid individual.

But addictions not only impact the person who has the “disease”, it impacts the people around that person. The disease model falls down in this regard, as no disease happens in a vacuum. It is in the relationships that the addict also suffers, as those relationships become increasingly subverted, leaving the person with addictions at peril of being as isolated as a person with leprosy used to be. As with any disease model, the impression of the people who share the community may perpetuate the myth that people with addictions are contagious, dangerous, and not to be trusted. Whether they have a disease or not.

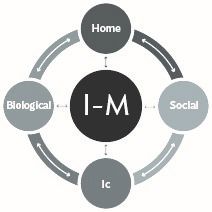

So how do we maintain the idea that a drug addict or alcoholic is not a person without morality, nor a person with a weakness of will, in-valid? How do we bridge the disease model with the potential of hope and sobriety, if not “cure”? One way is to redefine the way we not only see people with addictions, but with people in general. What happens when we remove the overlay of judgment? Instead of saying, “That person should be doing better. What’s wrong with them?”, why not begin viewing people as simply doing the best they can at that moment in time, with the potential to change and make different choices at the next or future moment in time? This leads to the model I have created and been developing at CASTLE, called the I-M approach. Seeing people at an I-M: a current maximum potential.

The I-M suggests that people are doing the best they can at every moment in time. It is controversial, but potentially changes the lens with which we view each other. And if a person is truly at an I-M, simply doing the best they can, what happens to pathology, to disease, as the brain and body respond the best they can to the conditions they face?

The I-M becomes a lens of respect.

You don’t have to like what a person does. You don’t have to condone it. The person will be held responsible for their actions. But you have to respect it, respect that given the influences of their lives, which I will explore next week, this is the best they can do at this moment, at this moment in time. Liking something and respecting someone are two different things.

Let’s look again at why someone does what they do without judgment. “Look” is from the word-root “spect”, like in spectacles. “Again” is from the word root “re”. Put those together = respect.

What happens when we see people at an IM and how does that have an impact on their brain? When is the last time you got angry at someone you truly perceived was treating you with respect? You don’t. The brain does not work that way. I believe this has the same reliability as gravity. Apples do not fall up and the brain does not activate anger when it feels respected. Anger is an emotion designed to change the behavior of someone else. But being respected feels great, so why would we want to change that?

I see this every day in my adolescent substance abuse program. Kids begin to feel respected. This leads them to feel valued. And this allows them the opportunity and environment in which to trust and really explore their addiction. We have had over 1900 kids come through the program from all walks of life.

At an average of 16 patients per day since 2008 we have had over 35,000 patient days. In all those days we have had fewer than 100 physical fights. The I-M Approach is a position of respect. Over the next several weeks I am going to explore the I-M Approach in the context of addiction. I hope you join me. It’s an I-M thing.