Friends

Boxes of Old Letters, Burdens or Treasures?

The demise of letter-writing.

Posted April 2, 2014

It is true that email from beloved friends can be printed out and given the heft of paper. I have done this. I then place each email in a file folder labeled with the friend’s name. But I prefer my shabby boxes filled with 30 years’ worth of letters from these same friends. When I open one of the boxes, I am greeted by envelopes of different colors and shapes, stamps of all varieties, and postmarks from places near and far. I see my name written in familiar handwriting, addressed to apartments and houses of my past, and I am transported back to earlier eras of my life. When I open a file folder of accumulated email, I remain unmoved as I flip through pages of bloodless, typed uniformity.

Handwritten letters are quickly becoming a thing of the past. All of us still delight in the discovery of a letter in the mailbox amidst the bills and advertisements, but dwindling numbers of us remain who actually write letters. We oddballs like to scribble our thoughts on paper, address the envelope, and put on a stamp. We find satisfaction in the thump of the mailbox, the start of a journey that will culminate in a loved one’s pleasure.

While in her early 70s, Carter Catlett Williams found a treasure trove of letters written by the father she lost when she was not quite two years old. The letters were in a box in her attic, having dwelled there and in previous attics for decades. She ended up spending several years reading, transcribing, and recording her reactions to these letters. During this undertaking, she entered into a living relationship with the father she never knew. How can words inscribed on yellowing paper have this kind of power?

Coming of age in the early 20th century, her father wrote ornate sentences full of finely observed details about people and places, ailments, longings and worries. One has the sense of being with him as he describes intimate details about his daily life in boarding school to his parents. In later letters, shortly before he was killed flight-testing an early plane, he conveyed sweet nuances to his mother and father about his infant daughter. It turned out that Carter’s father had left enough of himself behind in these letters that she could truly know him and could experience the love she couldn't remember.

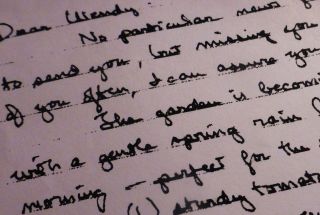

This feeling of being together through words in a certain time and place is the grounding of a letter; writing on paper occurs viscerally within the life being lived. The letter-writer often remarks how the light is beaming in through the window and lighting up the page, or how delightfully the smell of baking scones is suffusing the air around the kitchen table. The reader becomes situated along with the writer, easing into the mood as much as the context where the letter is being written. I’m sitting in a café downtown, with a double espresso and your latest letter in front of me. Such locating passages are almost never included in an email, even if a laptop were to sit on the same café table. The sensory dimension of life resounds through the letter-writer’s willingness to sit with what is there and spend these moments pen in hand, while such matters are literally immaterial in an email.

Letters are rooted in time, the way life is. It takes time to sit down, pick up pen and paper, and compose one’s thoughts. More time accrues in preparing the envelope and getting the thing over to a mailbox. Days elapse as the missive travels, and then it lingers for a bit longer until the recipient gets home. Finally, the letter is torn open. The person must slow the forward rush of life in order to read what someone else has taken the time to inscribe. Then writing back takes more time. Often, I will carry a letter around in my purse for weeks, until I have an interlude and setting suitable for responding. Re-reading the letter, I like to glance back and forth between different sections to be sure I have taken in the details where the pain or joy resides. All of this is part of encompassing the gift that a friend has finally unburdened herself or opened her heart.

The blurted voice rarely muses or ventures the way the written voice does, tending more toward instrumental than exploratory purposes. When I receive a paper letter, I like to spread out the pages and take in the whole – as can the writer. When I compose or read a long email, I find the screen cuts off the flow and causes me to get lost when I have to scroll through digressions. There is usually more depth and cohesion with writing on paper, arising chiefly from the freedom to wander away from the original point and yet be able to find the way back.

Are there any lovers anywhere who still wait for the mail? The waiting was part of it—watching for the letter-carrier down the block or listening for the creak of the mail box lid. Between letters, there was time to yearn and doubt. Email or text messages blurt their declarations, making the slow dignity of the letter laughable. Time for pondering and questioning, days on end for discerning exactly what one feels, belong to the days when people labored over letters. Whole courtships were carried on by letter. I have the fourteen-page tome Edna Whitman received in 1904 from Victor Chittick declaring his love for her and his wish to spend the rest of his life with her. It was found in her nursing home night table after she died at the age of 101. She had outlived their marriage of seven decades by twelve years, but this letter accompanied her to the end.

I am afraid that such life-changing reclamations will never happen again in human history, once all letter-writing has ceased and there are no more boxes of old letters in our attics. I look at my letter-filled boxes and picture how they will fill a recycling bin soon after my death. Recently, I offered to return a great quantity of letters a friend wrote to me in her tumultuous twenties and she urged me to toss them out. Perhaps the act of cherishing itself is being harmed by non-palpable media. The printed word on paper is outmoded technology; the written word on paper is ancient. Perhaps most of us no longer see any value in retaining such artifacts, using them to look back at the past, and allowing them to take up space.

“Dear, dear Mother” is how Carter’s father addressed his mother while away from home for the first time at age sixteen. Often, he closed his letters home, “With a heart full of love.” Emailers almost never bother to fashion a greeting beyond “Hi,” and many do not put in a closing at all. They tend to come to an abrupt halt with their last sentence, as though signing off with a name attached to a sentiment is just too retro. Almost everyone contends that email replaces the old kind of mail, some without awareness of what has been lost and others with outright dismissal of the idea that letter-writing is an art and it is dying.

Email is about hurry and transience. It’s so much easier. I can dash off a few thoughts to a friend and send it instantaneously. This kind of writing is actually much closer to speaking than the old kind of letter-writing. It is spontaneous utterance, the advantages of which cannot be denied. There are surely millions of people emailing each other regularly who would not have written a single letter by the old kind of mail. There are hordes of eighteen-year-olds leaving home for the first time who send several messages a day to their parents from college, and men and women overseas in the armed forces who have frequent contact with loved ones thanks to this advance in communication. Some do take the time to compose long, letter-like descriptions of their feelings and circumstances, and such accounts are deeply cherished.

Still, I get tearful when I glimpse the envelope containing the birthday card my Aunt Judy sent me a few days before she died. I have plenty of photos of her, but seeing my name in her handwriting is what evokes the sweetness of grief. Perhaps it is the evidence of having been addressed by her, the personal salutation—“Dear Wendy.” She held a pen in her hand and wrote my name. Handwriting calls forth a beloved person more vividly than a photograph or even a video. My young granddaughters, born into the internet age, may never know how it feels to see a loved one's handwriting on an envelope pulled from a mailbox. Already, handwritten letters speaking the language of the soul have become the rarest of treasures. Those that are saved may speak again when a desk is cleaned months later, or when a daughter seeks to know her father seventy years hence.

Copyright by Wendy Lustbader. Adapted from the afterword to Glorious Adventure by Carter Catlett Williams, published by the Pioneer Network, www.pioneernetwork.org