Aging

Live Like Your Life Depends on It

Why elders tend to be more vivacious than younger people.

Posted July 13, 2013

Elders are usually the most vivacious among us, but we are too busy to notice. We are running around, getting things done, while they are living life to the fullest. Stereotypes about aging are so insidious and the physical realities are so prominent that we miss seeing the inner radiance that so many attain.

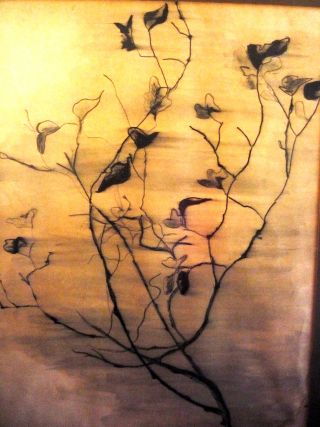

When my mother-in-law was dying, it took all of her strength to get down our steep front steps and take a walk around the block. We did this together as often as possible because it was what she lived for. As we made almost imperceptible progress down the sidewalk, she pointed out every garden ornament, artful decorations on mail boxes, each interesting texture on the bark of a tree. I had never seen my neighborhood before – not like this – even though I had traversed this sidewalk countless times on other walks.

At first, the slowness of our pace drove me wild. I had to conceal how infuriated I was and suppress the inner pressure of having so many other things to do. She would stop often, not because she was short of breath, but to get a better look at something. Eventually, I decided to put myself completely into the experience and let go of other concerns. How could I hurry a dying woman?

It was such a pleasure to do nothing but look around at the world. We should all live like this, regardless of age or proximity to death. Walking with her was like a prayer or a meditation. This was years ago now, and yet I still challenge myself to walk like that, to be receptive to this degree and really pay attention to all there is to see.

This is what aging and getting closer to dying teaches us – to live like your life depends on it. It seems as if it shouldn’t be necessary to get this old or this close to death to be able to seize the day the way my mother-in-law did, yet we are so easily sucked back in to days crowded with tasks and doings. Something has to slow us down, whether it is our becoming determined to do so or the approach of the ending.

Another insufficiently heralded part of aging is becoming more familiar with the humbling and therefore liberating aspects of having to die someday. In The Denial of Death, one of the great books of the twentieth century, Ernest Becker writes, "Man is literally split in two: He has an awareness of his own splendid uniqueness in that he sticks out of nature with a towering majesty, and yet he goes back into the ground a few feet in order blindly and dumbly to rot and disappear forever."

The problem with slowing down is that it puts us face-to-face with all that we have been avoiding, such as the poignancy of losing people we love and the almost perpetual grieving that living requires. We prefer to keep busy, avert our eyes and keep the happier subjects in view. Thus, a cycle ensues in which we try to elude the fact that everything and everyone is temporary. The more we avoid this truth, the greater is our fear of it. Conversely, if we embrace it, we grow calmer.

I have asked myself to try paying attention in a life-affirming way at least five minutes every morning, afternoon, and evening. Five minutes is a long time to pay attention. It’s not so easy to put aside my distractions and preoccupations. The nonstop buzzing in my mind about what will happen later in the day, the next day, and the day after that ceases only after concerted and prolonged effort. Also, to be confronted with what’s really going on inside of me isn’t always pleasant. The feelings hiding underneath constant activity rise right up and ask to be named.

My mother-in-law reminded me of the patient momentum of looking and really seeing, turning an ordinary walk into gladness for still being among the living. Most of the time, this is what I find – the gift it is to continue to be in the world. I welcome getting older because my capacity to enter into such vividness gets stronger every day.

Adapted from: Wendy Lustbader, Life Gets Better: The Unexpected Pleasures of Growing Older, Tarcher/Penguin, 2011.