Workplace Dynamics

The 4 Different Types of Workplace Friendships

3. "Workplace friendly."

Posted November 3, 2023 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- Workplaces function better when relationships are good than when they are not.

- Having friends at work is associated with innovation, job satisfaction, and engagement.

- We can choose to find some kind of friendship at work.

- There are work relationships that would not be classified as “best friends,” but that we still call friends.

In my undergraduate years, I worked with my friends, made good money, and ate free burgers.

I was a waiter at a 50s-style diner in Toronto, and I loved it. I never thought much about "liking people you work with" because having friends was part of the job.

Once I became a university professor and an executive educator, I learned that workplaces indeed function better when relationships are good than when they are not. Having friends at work is associated with innovation, job satisfaction, and engagement. And they are more important than ever.

These findings contradict what I’ve heard in my 20-plus years of working with employees at all levels: "We don’t have to be friends with people at work!"

I get how people end up with these views, but they are not helpful.

Not All Work Friends Are the Same

About 30 percent of North Americans have a bestie at work. Many more have friends at work who are not “best” friends but are still friends.

Surely, though, there are work relationships that would not be classified as “best friends” but that we might still call friends. We might know that they are certainly not strangers (or whatever the opposite of a friend is—a not-friend?). Various types of workplace friends would seem to fall between the extremes.

By specifying friendship types and understanding the benefits of each, we can make informed decisions about investing in specific workplace relationships.

There is previous psychological research about different types of workplace friendships. I have adapted these and included conclusions from my experience working with thousands of managers and leaders to develop “The Hierarchy of Workplace Friendlies.”

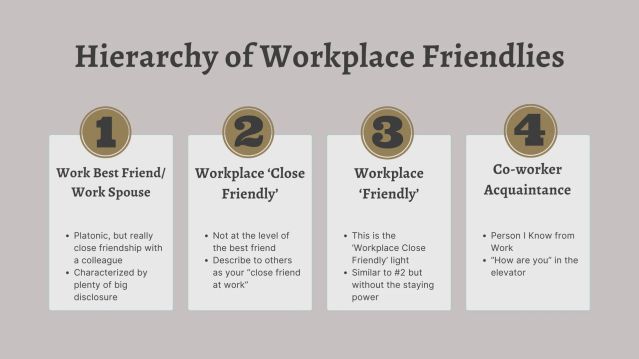

The Hierarchy of Workplace Friendlies

- Workplace Best Friend. A platonic but very close friendship with a colleague, characterized by disclosure, and where most topics are fair game. They hold each other in high regard and exercise trust and honesty. They have each other’s back.

- Workplace Close Friendly. These are not at the level of a best friend. They might be described as a “close friend at work.” They might want to remain good friends if or when they leave that workplace. It’s someone with whom you would hang out outside of work.

- Workplace Friendly. It’s the light version of the above. It has some of the same qualities but without the staying power. Pals at work, but less so outside. The friendship is less likely to persist beyond work, and there is little personal disclosure. It’s the work buddy—a coffee break, a chat about the kids, and the odd complaint about that annoying person in accounting (or HR).

- Co-Worker Acquaintance. This is the person you simply know from work. You may interact with them somewhat regularly, say hi, and say “How are you?” in the elevator. If you saw them at the grocery store, you would say hi or give a nod.

What is Realistic? What is Helpful?

The work best friend is the most helpful for employees and employers. But, given how rare, difficult, and downright exhausting they are to maintain, counting on this level is unrealistic. I’m tired just thinking about it.

The co-worker acquaintance would not provide any of the benefits that come from having friends at work—enhanced innovation, psychological safety, or the much sought-after benefits of vulnerability and compassion.

In 1945, Elton Mayo recognized that opportunities for social-emotional connections at work were crucial for performance. Merely sharing information does not provide these opportunities unless they become an emotional exchange.

The workplace close friendly and the workplace friendly seem like the best bets in terms of getting the benefits without being too draining. But the former would likely carry some of the same challenges as the work best friend. Too close, a potential for emotionally draining conflict spilling over into work, and far more difficult than the workplace friendly.

Because of the emotional exchange, all workplace friendships can be difficult. They require a significant time investment, as well as trust and disclosure, both of which can be daunting for some.

There are also real emotional risks with work friendships. An HR VP told me how, in his early career, a mentor advised him to "never be friends" with his staff because "you may have to fire them." He did not take the advice and instead chose to have “friendlies.” Sure enough, when he had to sever one of them, he was truly filled with guilt and sadness. Nonetheless, he said he would still opt for friendlies at work. The benefits outweighed the cost.

So, should we expect friendships from everyone at work? No. Do we need to try to find a way to get at least the workplace friendly? Yes. Is co-worker acquaintance adequate? Not really.

What Should We Do If We Don't Like Our Coworkers At All?

There are two options. The first is to vote with your feet. Make a choice. If you cannot stand that person and you must spend a ton of time with them, you can choose to remove yourself. But let’s be clear: This is a choice you can make but do not have to make.

The second option is to see the path to the workplace friendly. Deciding not to be nice or friendly and to instead keep important colleagues at arm’s length is not a good strategy. Some people do this hoping the colleague will get the message and suddenly change. Not likely. One might give up making it work, deciding, “It’s not worth it!”

But it is worth it. In the end, we will be happier.

To make it work, it's useful to question assumptions and find a new frame. My clients and students often find that using a metaphor helps—for example, A person is a restaurant.

Now, of course, a person is not a restaurant, but what kind of insight can we draw from this metaphor? Let’s say I go to a diner. They have great burgers, but the fries... not so fabulous. But I will probably still go back and get a different side dish because the burgers were so good.

Using metaphors in this way points to the utility of reframing perspectives to solve problems. Just like in any context in our lives, there are no perfect people—in or outside of work.

The way we look at the people we work with can help us make choices. If we choose to leave a job because we simply won’t or don’t want to make friends with the people there, then that’s OK. Hopefully, we can stick it out until we find something better. But because there will likely always be a difficult person, there may not be something better.

Or, if we are ready and able to do the work of reframing, we can try for the workplace friendly.

This choice can be rewarding in several ways—career-wise and personal development-wise. What is not great is wanting things to get better and then doing nothing. There is no workplace where we can easily make close friends without effort. This is an important point if you are planning to leave somewhere because you don’t like the people. There will always be one that we don’t care for. It can be empowering and comforting to know that, with some reframing, we can sometimes turn things around if we want to.

Facebook/LinkedIn image: Vadym Pastukh/Shutterstock