Career

What If Only I Am Ready/Willing To Work On Our Relationship?

Irrelationship or Irreconcilable?

Posted June 1, 2016

One of the most oft-recurring questions for people working through irrelationship is, “How do I get my unavailable or ambivalent partner to open up and discuss our relationship? What if they just aren’t ready?”

Clara had been hammering away at this seemingly insoluble problem in her relationship with Juan.

"I get, I get it!" she exclaimed in session one day. She and her therapist, Dr H, had spent months exploring why intimacy was missing from their relationship—intimacy she was sure she wanted. She was finally willing to consider the possibility that Juan’s “non-presence” had a two-sided meaning. “I guess you’re right: I’ve been living in irrelationship.”

"Uh, you? Only you?” Dr H asked.

"Okay, okay, we are."

After a thoughtful pause, Clara, obviously sad, continued, “But if I’m ready, and Juan isn’t, well, then—then we aren’t ready.” Another pause. “I just wish there was something I could do. We could be so good together. It seems crazy that I—no, that we—can’t make it work. But we have trouble having even an adult conversation about just—us.

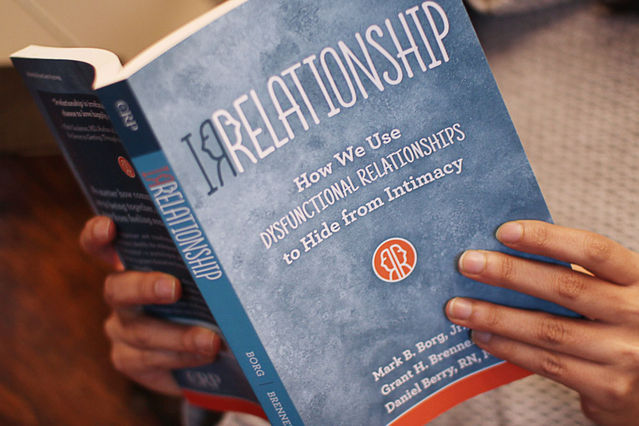

“I gave him a copy of the book on irrelationship. He read a few pages and then suddenly he had something else to do. And since then, whenever I bring it up, he says it doesn’t have anything to do with us.”

If you’re trying by yourself to save your relationship, you’re probably what, in irrelationship terms, is called a Performer. The solution may lie in enlisting your partner in an open communication process that exposes your song-and-dance routine and develops into what the authors call relationship sanity.

However, your wanting to “make it happen,” probably won’t be enough to enlist an ambivalent partner. But if you strike at the right moment, your partner may be able to acknowledge the problem, allowing a new, shared perception of the distance between you to surface, even if only for a moment. If so, you need to be sure this is really what you want: a paradox of irrelationship is that our partner’s elusiveness is often what incites our desire. But if he stops ducking, running or hiding, we may find that intimacy frightens us as much as it does our partner, exposing what Jessica Benjamin (2007) calls "complementarity.” Thus we expose how hard it is to admit our own vulnerability even to ourselves—what might be called “irrelationship with oneself”.

"Okay, what now?" continued Clara. "Juan seems oblivious to the deadspace between us. If I bring it up, he says, ‘Things are fine—what’s the problem?’ The conversation stops, a wall goes up, and I’m on the wrong side of it. By myself. Again.” Am I just making a fool of myself? If he won’t even acknowledge the problem, where is there for me to go?”

Dr H paused before answering. "It’s hard to know without hearing what Juan has to say. But from what you describe, the distance may be as painful to him as to you. If he doesn’t talk about separating, he may still want connection with you, but senses that in talking about this, he’s going to have to talk about his vulnerability—something most of us don’t like doing.”

“Yeah, I see that. Well, if we’re both scared, how do we start?”

“Well,” said Dr, H, “ you’ve already stumbled onto the first step of working through irrelationship: you’ve discovered its existence. And you might be able to start the change process by using certain tools that you can ask Juan to use with you. Sometimes they work right away, but usually people have to get used to them before they can really work. You have to decide if it’s worth it to you—to both of you—to find out if it might work.

“It doesn’t require 100% buy-in from both partners—not at first anyway. But just deciding to try the tools can create a new openness that allows you to listen to and hear each other in a way that can change everything—and I mean everything—about your relationship.”

The process Dr H is referring to is called the 40-20-40. The 40-20-40 creates a non-judgmental space in which couples can build compassionate empathy and mutual understanding by sharing their feelings and experience without fear of criticism, blame or retaliation. The way it works is described here.

By practicing the 40-20-40 (no one gets it “right,” especially not at first: in fact, getting it “wrong” is a vital part of the process) couples and even individuals invested in irrelationship transition into relationship sanity. Relationship sanity allows us to share our relationship experience in deeply intimate terms. Reflecting on the process brings up such questions as:

What is it like to be forming the experience of sharing your heart and mind—in that way that you behave with and relate in the presence of those who matter most? What is it like to discover that there may be hope to relate in a totally different way than you have know, and break out of the prison of isolation?

What is it like to finally be able to listen fully? To appreciate what someone becoming increasingly valuable truly has to offer?

What is it like to see someone else, your partner, going through this? What is it like to experience another’s vulnerability in the face of emotional risk and investment, as you become increasingly important, yourself?

What is it like to sense your own—each other's—long-suppressed emotional investment in another person?

What is it like to begin to feel comfortable with, even empowered by, the uncomfortable experience of your own vulnerability as you start to see how much richer intimacy can become as mutuality develops?

After discussion of these questions, and others, with Clara, Dr H asked her, “Do you think your connection with Juan might be worth it? How would you feel about deliberately trying to know each other better than you ever have?”

"Well,” Clara replied, “it’s scary. But I also still remember the Juan I fell in love with; and he is still here. I don’t think I’d be here if I wanted to walk away from ten years together like it was just a big mistake. Maybe we really can find each other again.”

Reference

Benjamin, J. (2007). Intersubjectivity, thirdness, and mutual recognition. A talk given at the Institute for Contemporary Psychoanalysis, Los Angeles, CA.

To order our book, click here. Or for a free e-book sample, here.

Join our mailing list: http://tinyurl.com/IrrelationshipSignUp

Visit our website: http://www.irrelationship.com

Follow us on twitter: @irrelation

Like us on Facebook: www.fb.com/theirrelationshipgroup

Read our Psychology Today blog: http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/irrelationship

Add us to your RSS feed: http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/irrelationship/feed

The Irrelationship Blog Post ("Our Blog Post") is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice. We will not be liable for any loss or damage caused by your reliance on information obtained through Our Blog Post. Please seek the advice of professionals, as appropriate, regarding the evaluation of any specific information, opinion, advice or other content. We are not responsible and will not be held liable for third party comments on Our Blog Post. Any user comment on Our Blog Post that in our sole discretion restricts or inhibits any other user from using or enjoying Our Blog Post is prohibited and may be reported to Sussex Publisher/Psychology Today. The Irrelationship Group, LLC. All rights reserved.