Left Brain - Right Brain

Drawing on the Right (and Left!) Sides of the Brain

Is it true that upside-down drawing improves accuracy?

Posted November 30, 2019

In 1979, Betty Edwards published the book Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, which remains the preeminent book on the subject of drawing for beginners. In the book, Edwards argues that there are two separate pathways through which the brain processes visual information. The left side is described as being analytic, verbal, and numeric, while the right side is holistic, perceptual, and creative. The key to learning how to draw, according to Edwards, is to suppress the biases and preconceptions originating in the left side of the brain and focus on the more naive, Gestalt approach of the right side.

The method includes the notion of upside-down drawing—the idea that when learning to draw by copying, it is preferable to turn the to-be-drawn object upside-down. The effect of a 180-degree rotation is to silence the left brain's preconceptions about what the drawn object is supposed to look like and allow the right brain's perceptual processing and creativity to take over.

Although the upside-down drawing method has been taught in countless art classes, the research on its effectiveness has been less than compelling. For example, a meta-review of the laterality of creative processes conducted by Dietrich and Kanso (2010) found no evidence that the right and left brain hemispheres contribute differently to creativity. Furthermore, the idea that drawing upside-down objects, including faces, leads to more accurate depictions has not been supported scientifically.

In a recent study, Dr. Jennifer Day and I explored the question of whether naïve participants (not trained in drawing) would produce more accurate face drawings when presented with upside-down vs. upright faces (Day & Davidenko, 2018). In order to generate easy-to-draw faces for the experiment, we constructed a parametric face space based on 400 real human faces, which allowed us to produce a number of unique faces to be drawn. The methodology to generate these faces is described in detail in Day & Davidenko (2019).

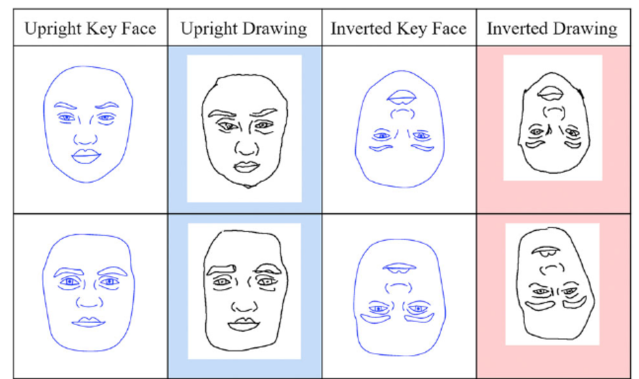

Participants in the drawing study had 90 seconds to draw each of 16 faces, which could be presented upright or upside down. The figure below shows examples of drawings of upright and inverted faces, produced by different participants:

We evaluated the accuracy of each face drawing using four separate metrics:

(1) A physical measure based on the Euclidean distance in face-space between the drawing and the original face

(2) A physical measure based on the angular deviation in face-space between the drawing and the original face

(3) A perceptual measure of similarity based on similarity ratings from a new group of participants comparing the upright-drawn and inverted-drawn faces (all presented upright)

(4) A perceptual measure of similarity based on similarity ratings from a new group of participants comparing upright-drawn and inverted-drawn faces (all presented upside-down).

All four metrics pointed to the same result: Upright (not upside-down) drawings were more accurate. Despite what is suggested by Betty Edwards and the upside-down drawing method, the drawings of upright faces were deemed as more similar to the original faces than the drawings of inverted faces, according to both physical and perceptual measures of accuracy.

What is behind these results?

There may be some actual advantages to drawing upside-down faces—certain biases of what we expect a nose or a mouth to look like are likely suppressed when we are drawing upside-down faces that are less familiar to us. However, drawing upside-down faces also presents disadvantages that may outweigh the advantages. First, your brain may find it more difficult to remember what you are drawing when you look away from the target to your drawing and back.

Even more critically, you may find it difficult to judge how well your drawing is coming out when looking at it upside-down. The expertise we have with faces, which allows us to judge whether two faces are similar, is severely limited with upside-down faces. This impairment may interfere with our ability to judge the accuracy of our drawings in real-time and make the necessary corrections.

All in all, drawing is a complex perceptual and cognitive process that takes years to train. Although turning an object to be drawn upside-down may help in early stages by suppressing visual biases, it also interferes with our ability to remember the to-be-drawn object and judge the accuracy of our drawing as it progresses. The key to improving one's drawing abilities, then, may be to learn how to suppress visual biases without turning stimuli upside-down, thereby retaining the visual expertise necessary to produce a good likeness.

References

Dietrich, A., & Kanso, R. (2010). A review of EEG, ERP, and neuroimaging studies of creativity and insight. Psychological bulletin, 136(5), 822.

Day, J. A., & Davidenko, N. (2018). Physical and perceptual accuracy of upright and inverted face drawings. Visual Cognition, 26(2), 89-99.

Day, J., & Davidenko, N. (2019). Parametric face drawings: A demographically diverse and customizable face space model. Journal of vision, 19(11), 7-7.