Deception

Reading While Sideways

How the orientation of words and our bodies affects our ability to read

Posted October 31, 2019

Reading is an extremely complex visual cognitive task that takes years to train. What expert readers can do at a quick glance might take a novice reader several minutes of effortful decoding.

However, reading–like many other complex visual tasks–is very sensitive to orientation. Have you ever tried reading a book upside-down? Do you ever find yourself tilting your head to read a title printed vertically on the spine of a book cover? The difficulty of reading text that is not upright reveals that our expertise in reading, as great as it may be, is fundamentally limited to a particular range of angles at which the text can appear.

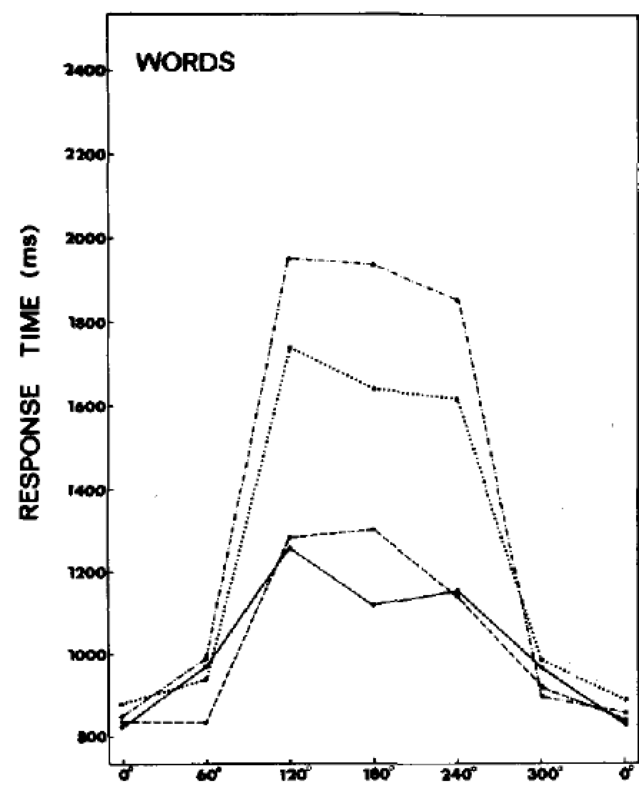

Indeed previous studies examined how reading speed and comprehension are affected by the orientation of words. An early study conducted with Hebrew readers found that participants' responses time to detect whether a string of letters was a real word or a nonword (i.e. a lexical decision task) took considerably longer when words were tilted by 120 degrees or more on the screen, compared to upright words (Koriat & Norman, 1985). In contrast, words tilted by only 60 degrees showed almost no cost in lexical reaction times. The psychometric curve that represents participants' average reaction time as a function of word orientation (Figure 1) shows a non-linear trend.

This non-linearity suggests that we are not merely "mentally rotating" rotated words when we try to read them. Instead, the research suggests there may be a two-part process: for relatively small rotations (-60 to 60 degrees) words can be read automatically without requiring effortful mental rotation. For larger rotations beyond 60 degrees, a more deliberate process of mental rotation may need to occur. This mental rotation process requires more effort the longer the words are.

Until recently, most research examining reading behavior considered only situations where participants were sitting upright, reading words on an upright monitor. A limitation of this past work is that people often like to curl up with a book; we often read while lounging or lying sideways. Is the psychometric curve that describes how efficiently you can read as a function of word orientation affected by your body position?

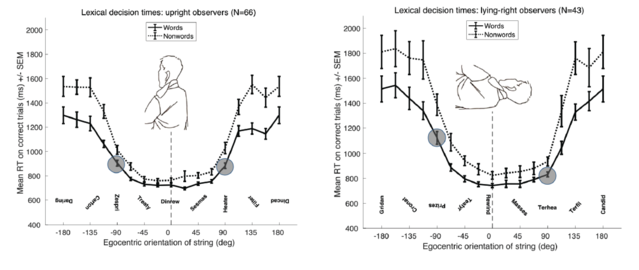

In a recent set of studies conducted at UC Santa Cruz, my co-author Alexander Ambard and I examined this question by engaging participants in a lexical decision task while they were either sitting upright or lying sideways at a 90-degree angle (Davidenko & Ambard, 2018). According to one theory–the internal reference frame hypothesis–body position should have no effect on reading time. That is, as long as words are upright relative to the reader's head, reading time should not be affected. However, according to the multiple reference frames hypothesis, our sense of orientation is affected by our body and head position as well as external cues. In particular, when we are lying sideways, we tend to create an intermediate reference frame that combines our internal (i.e. retinal reference frame) and external (i.e. gravitational, environmental) reference frames. We previously found that when people lie sideways, they combine these reference frames when recognizing rotated faces (Davidenko & Flusberg, 2012) and when telling time on analog clocks (Davidenko et al., 2018).

Our results, shown in Figure 2, indicate that people do in fact combine multiple reference frames when reading rotated words. When they are upright, participants showed a typical psychometric curve, similar to the one found by Koriat & Norman over thirty years earlier (Figure 2-left; note that the graph is re-centered at 0 degrees). However, when participants were lying sideways, the psychometric curve shifted to the right, by approximately 20 degrees (Figure 2-right).

This means that if you are lying sideways, the optimal orientation to hold a book is not perfectly upright relative to your head, but rather at an oblique angle, about 20 degrees away from your internal upright, towards the external (gravitational) upright. Furthermore, we found that the precise angle at which reading performance was optimal varied considerably among individuals–for some participants, the optimal angle was about 30 degrees and for others it was closer to 10 degrees.

When it comes to reading a book in bed, one can easily adjust the orientation of the book to approach this optimal angle. But when reading text on electronic displays, like a smartphone or tablet, the sensors that detect and try to correct for the orientation of the display can make this difficult. For example, if you are lying at a 65-degree angle you may want to hold your book at 45 degrees. You may find that your phone or tablet will try to automatically "correct" this by flipping the screen to landscape or portrait mode. Given the individual variability in optimal reading angles, technology may need to catch up to give people the same flexibility afforded by good old fashioned physical books.

References

Koriat, A., & Norman, J. (1985). Reading rotated words. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 11(4), 490.

Davidenko, N., & Ambard, A. (2018). Reading sideways: Effects of egocentric and environmental orientation in a lexical decision task. Vision research, 153, 7-12.

Davidenko, N., & Flusberg, S. J. (2012). Environmental inversion effects in face perception. Cognition, 123(3), 442-447.

Davidenko, N., Cheong, Y., Waterman, A., Smith, J., Anderson, B., & Harmon, S. (2018). The influence of visual and vestibular orientation cues in a clock reading task. Consciousness and cognition, 64, 196-206.