Artificial Intelligence

Our Four Realms of Existence: The Biological Realm

Every living thing that has ever existed has existed biologically.

Posted October 31, 2023 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- Early on, biological science was challenged by vitalism, which attributed life to vital spirit forces.

- Spiritualism continues in everyday life and sometimes slips into science, where it does not belong.

- Artificial intelligence is another threat to biological science.

This is the second in a series of posts about my book, The Four Realms of Existence.

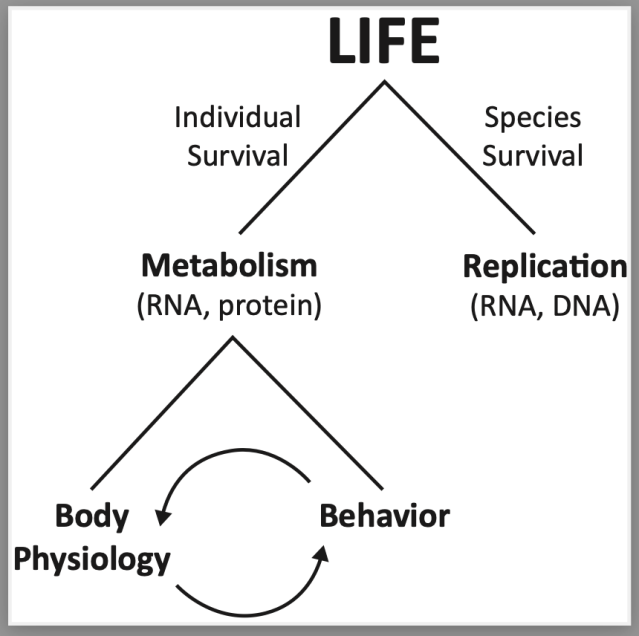

The world we live in is filled with things that we distinguish from other things. Perhaps the most fundamental difference is between things that are alive and those that are not. Living things, organisms, are biological beings that possess basic life-sustaining processes such as metabolism, as well as the species-sustaining capacity for replication/reproduction. Animals, plants, and unicellular organisms are living things—that is, biological organisms. Rocks, water, and minerals are not alive and are instances of mere physical matter.

Every living thing that has ever existed has existed biologically. This primordial realm of life has existed for roughly 3.7 billion years. It is a preexisting condition for the persistence of life over time and, therefore, is the core of every living thing, whether a single-cell microbe, such as a bacterium, or a complex multicellular organism, such as a plant, fungus, or animal.

Vitalism

Just as the field of biology was getting going in the 18th century, a movement called "vitalism" threatened a fundamental biological principle—that life is a particular kind of physical condition. Vitalists, by contrast, proposed that a nonphysical essence, a vital force or spirit (not in the religious sense of spirit, but not far from it, either) underlies life. This was a complicated time for the direction the young field of biology would take, as pioneering biologists like Louis Pasteur, Johannes Müller, and Xavier Bichat were proponents of vitalism.

Claude Bernard, who coined the expression, "the internal milieu" (le milieu intérieur), was a critic of vitalism but was accused of leaning toward spiritualism because of his rejection of Darwin’s theory of evolution. In response, he said that spiritualist views like vitalism and creationism are nonscientific expressions of faith in the supernatural and do not have a role in science.

Bernard’s internal milieu went on to inspire the 20th-century notion of "homeostasis" (the balance between the inner and outer environment), and the idea that metabolism sustains life. But missing was a means by which species evolve and traits are passed from generation. Watson and Crick’s discovery of DNA as the mechanism of inheritance solved that.

Organisms evolve through natural selection. Quite often, new (or newly changed) features become the primary target of natural selection, with selection based on old features being less common and, in fact, suppressed. For example, basic life-sustaining physiological functions of the body, like metabolism, have been repeatedly tested for their survival value by natural selection and, therefore, have tended to change relatively little in the evolution of new species. More often, changes involve processes that control the way the organism’s particular kind of body interacts with its environment in satisfying its life-sustaining needs. In general, fundamental changes in organismic life tend to arise gradually.

But sometimes radical changes occur. These are called "major evolutionary transitions." Examples include the transition of inorganic matter to biological life, the evolution of multicellular from unicellular life, the evolution of nervous systems in animals, and the evolution of cognition and consciousness in some animals with nervous systems. In other words, the emergence of each of the four realms of existence was a major transition.

Genetic inheritance, metabolism, and homeostasis are a far cry from the mysterious, nonmaterial, spiritual forces proposed by vitalists and creationists. Spiritualism continues in everyday life, including in the life of some scientists, and that is fine. But sometimes it slips into the practice of science, which I do not think is fine. In the science of consciousness, for example, the integrated information theory holds that mind (consciousness) exists to some extent throughout the living world, but also in nonliving matter on earth and in the rest of the universe, a view called "panpsychism" (consciousness is everywhere). Panpsychism is a legitimate topic in philosophy, where some view it as a bridge to "pantheism" (God is everywhere). Metaphysical ideas like vitalism, creationism, panpsychism, and pantheism, have no place in science.

Artificial Intelligence

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) pose a different kind of threat to the biological basis of life. A machine with a program is simply a machine with a program—nothing more. We humans exist and function the way we do because we are the result of a 3.7-billion-year evolutionary history of gradually accumulated and intricately entwined changes in body design, with each new step having been built on previous ones. By contrast, AI-driven machines have not evolved biologically and, therefore, have not gone through the history of maturational changes that instantiate our biological existence, including what we humans refer to as "consciousness." AI, as its moniker, "artificial," implies, is, in some instances, an excellent mimic of biological life. But it cannot literally re-create it. Problems especially arise with claims of conscious AI. Conscious AI, to me, is an oxymoron.

There are many ways to discuss the organization of biological life. But one that I find very useful was proposed by the comparative anatomist Alfred Sherwood Romer:

In many regards the vertebrate organism, whether fish or mammal, is a well-knit unit structure. But in other respects there seems to be a somewhat imperfect welding, functionally and structurally, of two somewhat distinct beings: (1) an external, 'somatic', animal, including most of the flesh and bone of our body, . . . and (2) an internal, 'visceral', animal, basically consisting of the digestive tract and its appendages, which, to a considerable degree, conducts its own affairs, and over which the somatic animal exerts but incomplete control.

Romer's somatic and visceral ways of existing make up two fundamental components of the biological realm. Although he emphasized vertebrates, his distinction applies to all life forms—even single-cell microbes have visceral and somatic functions. As I will discuss in the next post, on the neurobiological realm, the somatic-visceral partition defines two fundamental components of the nervous system.

Although I have said a lot about the evolution of our four realms, as we go forward in this series of posts, my emphasis will shift away from which organisms have which realms and toward how the realms manifest in the human organism.

References

J.E. LeDoux (2023) The Four Realms of Existence: A New Theory of Being Human. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.