Eating Disorders

Treating Eating: New Research

A new article on why a behavioral focus is key to eating disorder treatment.

Posted July 31, 2020 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

What’s wrong with eating disorder research and treatment, and what would make both better?

It’s easy to speculate on big questions like this, and a blog is a lovely vehicle for exploration from multiple different starting points: from personal experience; from interesting research findings; from the questions and testimony of you, my readers—often from an amalgam of all three, and observations on life in general.

But in the end, it’s important to systematise a bit: to attempt a more comprehensive formulation of how, really, eating disorders could be pre-empted and healed more effectively than they are (on average) today; how less time and resources could be lost to ineffective intervention and the suffering that results; how we could get our act together when it comes to eating disorders.

This is what my co-author Michael Leon and I have attempted in a paper (Troscianko and Leon, 2020) that came out this weekend in the journal Frontiers in Psychology. It came about because of this blog. Michael emailed me at the end of the summer of 2017, as follows:

Dear Emily,

You may be quite interested in our treatment for anorexia, which is based on the idea that anorexics need to relearn how to eat. We use a scale that communicates with an app that allows feedback about the rate and amount of food that is eaten compared to the normal eating pattern for that meal. You can read about our approach in our many published articles: https://mando.se/en/. We have a 75% remission rate for our patients, with 10% relapse and 0% mortality in over 1500 patients, about a quarter of whom are seriously affected to the point where they must be inpatients to stabilize their physiology. By the way, the treatment is also effective for bulimia, binge-eating disorder and obesity, as they address a common problem.

Best,

Michael Leon

Professor and Associate Dean

Department of Neurobiology and Behavior

School of Biological Sciences

University of California Irvine

I was intrigued, I happened to be up the road in Pasadena at the time, and we soon met for lunch at Irvine. When we met, Michael mentioned that it was stumbling across my blog post on the Minnesota starvation study that had encouraged him to write: he (like me) thinks that more should be learned from its methods and findings in contemporary eating disorder treatment and research.

Our Californian conversation led, the following spring, to a visit to the Mando clinic in Stockholm, which in turn led to my blog posts on CBT and Mando. Then in August 2018 Michael asked whether I’d be interested in collaborating on an article for a special issue of the journal Brain Sciences on “Psychotherapeutic Treatment for Anorexia Nervosa”, with a focus on personalised approaches. We had a year until the deadline, and in true academic fashion had great intentions of starting work with seven months to spare, and then didn’t properly begin until two months before. That might just about have worked, but it turned out, over the nearly two years to come, that we had an awful lot to work out about what we wanted to say and how exactly to say it.

Michael’s original idea was to “propose a unified theory of body weight control”. Given all the tricky connotations of concepts like “control” in anorexia, even when not attached to objects like “body weight”, I was aware from the outset that there would be interesting collaborative work to do in defining our object of inquiry and then converging on an angle to adopt. But I didn’t expect just how profound a process of construction and reconstruction the writing would turn out to be. As it happened, this was the first major academic project whose time investment I tracked from beginning (well, from the moment I started properly working on it in June 2018, rereading my meeting notes and making a plan), and the grand total focused working hours ended up being 84.5—21 of them just on addressing the reviewers’ comments. And that’s just my input.

One of the main transformations that happened, sometime late last year, was losing half the article. (It still ended up right up against the journal word limit, so I guess the hacking-up was doubly necessary.) The original idea was that we would consider eating disorders and obesity as two manifestations of the same basic principle: as Michael put it in an early email:

obesity is often regarded as a problem of self-esteem, and other psychiatric issues. The fact that it can be treated in the same way that eating disorders are treated leads to a unified theory of body weight control, where emotional and psychiatric issues take a back seat to the behavioral and physiological issues that actually drive these body weight problems.

A year later, though, on the back of some helpful comments from colleagues, we concluded that the evidence base for behavioural treatments for obesity of the type we were focusing on is just not well enough developed (though the failures of most other types are substantially demonstrated), and that there was a problematic asymmetry between the solidity of the evidence for obesity versus eating disorders. We decided that the “unified theory” would have to be reined in for now, and that our arguments would be more strongly defensible with a narrower focus on “just” eating disorders.

The original special issue was a ship long since sailed, and publication venue was now a tricky question, because as I described in the Mando post, the mainstream of eating disorders researchers have not been welcoming to the Mando team’s efforts to generate debate and further research on the power and scope of squarely behavioral interventions, including the roles of specific elements like eating speed or warm rest after meals. They have typically met with silence, declined invitations, personal hostility, or obstructive publishing practices. So we decided to choose Frontiers because they practice a variant on open peer review where reviewers names are withheld during the review process but published alongside the paper afterwards. This is designed to lead to more measured comments than sometimes arise under the cover of anonymity. We then had the choice between Psychiatry and Psychology, and decided this is probably too squarely behavior-focused to meet with good reception from psychiatrists. Then I realised that Frontiers in Psychology have an “Eating Behaviors” theme, which seemed a perfect fit. Our two (female) reviewers were, we’re happy to report, fair and constructive in their criticisms and suggestions, and made the paper better.

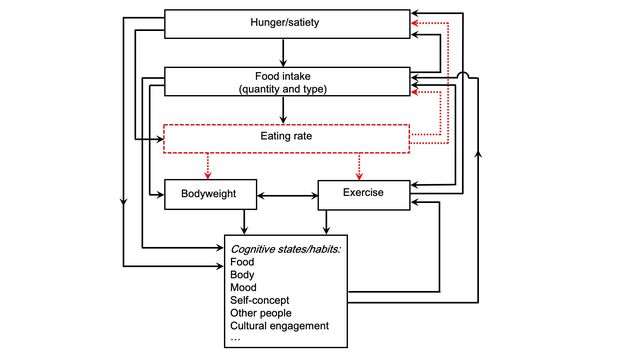

So, here it is: an argument for treating eating disorders as feedback systems, in which cognitive and physiological factors are in play, but where the most effective intervention point is almost always the behaviors of eating itself.

We offer discussion of why the “psychology first” perspective persists despite decades worth of evidence that it generates treatments that remain, on average, impressively ineffective.

We try to explain why CBT is founded on the very same principles of dynamical feedback systems but fails to capitalise on that inheritance—for both theoretical and practical reasons.

We offer up reasons why eating speed in particular may be a powerful place to intervene when eating has gone wrong, and has brought a lot of other things down with it.

We acknowledge the necessity of never ignoring any aspect of mind–body–world feedback, but equally of not getting distracted by the fascinating complexities of the mental side of things, or the satisfying measurability of the physical side of things, and forgetting that in the end, the way to treat an eating disorder is to treat the eating.

The article is open-access here: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01801/full.

References

Troscianko, E. T., & Leon, M. (2020). Treating eating: A dynamical systems model of eating disorders. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1801. Open-access full text here.