Fear

Cancer-phobia: How Our Fear of Cancer Harms Us

Our fear of the disease can by dangerous all by itself.

Updated November 17, 2023 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- Despite great progress, we fear cancer more than any disease.

- Recognizing the damage that our fear of cancer causes can help reduce the harm.

- Estimates of that harm on our health, financial and otherwise, are sobering.

This is the third in a series of posts based on my new book Curing Cancer-phobia: How Risk, Fear, and Worry Mislead Us.

We fear cancer for good reason. It is a major cause of death and can be an awful way to die. But we also must recognize that in some ways our deep, reflexive fear of “the C-word” exceeds the actual risk and ends up doing serious harm to both our individual health and society in general.

In terms of health damage, things start with cancer screening. In the U.S., four types of cancer screening have been found to be “effective” (defined by the National Cancer Institute as reducing the number of people who die, and providing more benefit than harm) for asymptomatic people with no other risk factors, like genetics. These are mammography, cervical cancer “Pap smears” and human papillomavirus (HPV) tests, special CAT scans for lung cancer, and various types of colorectal screening. But even these are only recommended for certain people and at specified frequencies, based on who is more likely to be helped than harmed.

Yet millions of people outside of those groups seek the reassurance of screening against their fear of cancer—people whom research has found are more likely to be harmed than helped.

- In 2017, when mammography was recommended once every other year for women between 50 and 74, 15.6 million women under 50 and 5.7 million over 74 said they’d had one at some time in the past 10 years.

- Colorectal cancer screening was recommended for people from 50 to 75, yet 251,000 people below 50 and 1.1 million over 75 screened anyway.

- The PSA test for prostate cancer isn't generally recommended at all, because its harms outweigh its benefits, but it is advised that men between 50 and 75 talk to their doctors about having a test. In 2017, 3.9 million men under 50 and 6.2 over 75 had a PSA test anyway.

This "overscreening," largely driven by our fear of cancer, adds to the overall harm that screening, including for those within the recommended age groups, causes. First, there are the false positives—initial findings suggesting the frightening presence of cancer that follow-up tests show were just false alarms. Over 10 years of mammography, one woman in eight will go through this worrying experience, which research has found can do lasting psychological damage. The PSA test is wildly inaccurate. Two-thirds of men who get a frightening initial “You may have cancer” warning, leading to painful and risky biopsies (3-4 percent of which lead to hospitalization to treat infections), find out that the scare, which can have long-term emotional effects, was a false alarm.

But false positives are just the beginning. Over the 30-40 years since widespread cancer screening began, we’ve learned that many of the early cancers that screening can detect are overdiagnosed; they never go on to cause any harm in the lifetime of the patient. It is stunningly contrary to popular belief, but some types of breast, prostate, thyroid, and even lung cancer are so small and so slow-growing that patients with such diseases die with it, but not from it—and if it weren't for screening, they would probably never even know they had it.

Not all cancers kill. But most patients given a diagnosis of cancer, even if they are told they have a slow-growing, low-risk type that doesn't have to be removed right away and can just be monitored, opt for far more aggressive treatment than their clinical conditions require. They have mastectomies or prostatectomies or thyroidectomies—overtreatments that are more like “fear-ectomies” to remove the disease that frightens them but doesn’t necessarily threaten them. These treatments have side effects that range from moderate to death.

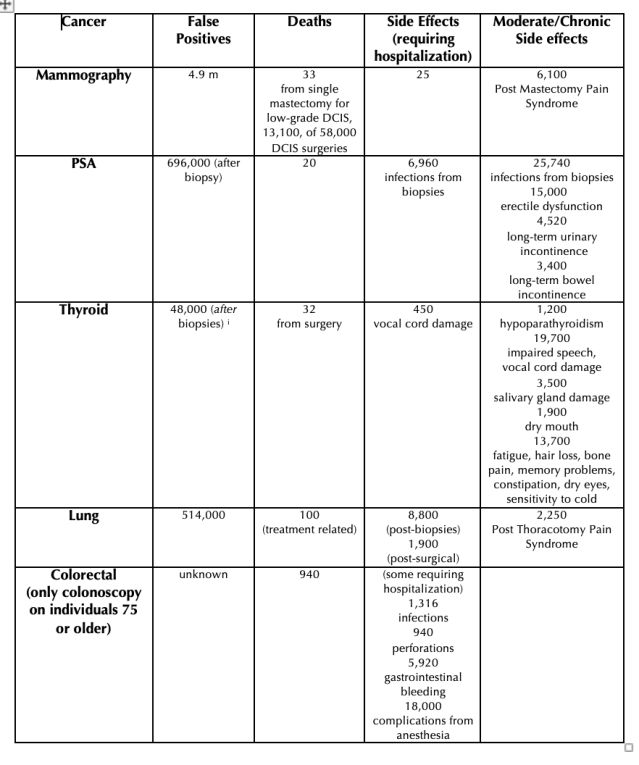

Rough estimates of the harm from these treatments made for Curing Cancer-phobia are sobering, as shown below:

Annual Harm from Screening and Treatment of 5 Overdiagnosed Cancers (U.S.)

(as of 2017, before active surveillance/watchful waiting was offered for prostate cancer and before a diagnosis of low-risk thyroid cancer was re-named to eliminate the word "cancer")

Now let’s consider the effect of all of this not only on individual health but on the health-care system. Overscreening, just on those outside the groups for whom screening is recommended, costs the U.S. healthcare system roughly $9.2 billion per year. The overtreatment of overdiagnosed cancer costs the system roughly another $5.3 billion a year. That’s 3 percent of all the money spent in the U.S. on cancer care annually.

And there are yet more economic costs to society. Surgery performed on people with overdiagnosed cancer costs the U.S. economy roughly 1.5 million work days per year, a $1.7 billion cost to the economy in lost productivity.

It’s important to qualify that these calculations (explained in greater depth in my book, Curing Cancer-phobia: How Risk, Fear, and Worry Mislead Us), are crude—and purposefully conservative. It is also vital to note, as I respectfully do throughout my book, that these figures look at things from the 30,000-foot, population-as-a-whole level, but we make our choices about screening and how to handle diagnoses of low-risk cancer on our own personal level, where even one in a million may seem too high if we could be that one. The choices any individual makes are theirs and theirs alone, and not to be judged as right or wrong, wise or unwise.

But considering the issue at the broader level, there is no question that our fear of cancer can in some cases cause great harm all by itself. And the costs to society of that fear extend far beyond those to the health care system alone.

References

[i] Malheiros, D.C., Canberk, D.N., Schmitt, F., Thyroid FNAC: Causes of false-positive results, Cytopathology, 2018 Oct;29(5):407-417