Sport and Competition

Which Is Better, Support or Competition?

What kinds of social media networks are best for helping you to exercise?

Posted November 28, 2018

What kinds of social media networks are most effective for promoting healthy levels of physical activity, competitive interactions or supportive social contacts? My colleagues and I at the University of Pennsylvania conducted a study to answer this question, and what we found will surprise you. One kind of social media network dramatically improved people’s exercise behavior; the other backfired.

The main findings, first published in Preventive Medicine Reports (2016) and explored with practical applications in How Behavior Spreads (2018), show that social media can indeed help people to exercise more, but only if it is used in the right way. Implemented incorrectly, social media can actually backfire and lead to less exercise.

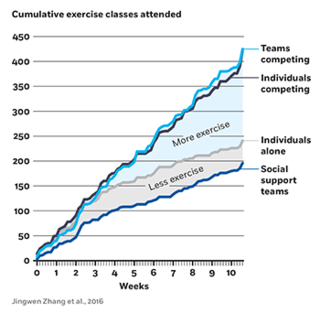

The most encouraging finding was that social comparison — that is, friendly competition — was really effective at improving people’s levels of physical activity. The most surprising thing we found was that social support networks actually led people to exercise less. Our results showed not just that support was worse than competition, but that it was worse than giving people nothing at all. Social support backfired, actively preventing people from going to the gym.

Why competition worked so well

Competition works because we naturally compare ourselves to people like us, and use them to evaluate whether we're doing better or worse than we should be. If we see others doing better — e.g., getting back into shape faster, going to more fitness classes, and losing weight more quickly — it gives us a new goal. Peer competition is very useful for goal-setting, and for creating aspirations for getting into shape faster. Done properly, social media networks can create a positive reinforcing loop in which everyone’s activity motivates everyone else to keep up their routine. This creates a natural "social ratchet effect," in which each person’s activity feeds back to generate more activity among the others.

Why social support backfired

Social support had a negative effect on participation because people did not use their peers as sources of social comparison, but instead as sources of encouragement. While the upside of encouragement is that group members can help to pull each other up, they can also pull each other down. What we observed was that the least active members of the group created a kind of social inertia that pulled the others to exercise less. Without friendly competition as a motivation for exercise, people were relying on their interactions with others to keep them motivated. We found that people can then use inactivity among their online peers as an excuse to lower their own levels of activity, which creates a downward spiral of activity in the network.

How do these findings compare with previous research?

Looking back over most of those studies, what I have found is that even studies that emphasize the value of peer support networks to encourage physical activity typically include some form of implicit social comparison within their interface. For instance, people may see a record of other people's fitness activity, or their cumulative number of days of participation, or their total number of calories burned, etc.. In other words, while it might seem as if the reason for the people’s success in these programs was the social support tools the programs offered, a closer look will typically reveal that there is some kind of social comparison feature built into successful programs. Even when we think that social support is helping, usually the explanation is that people are being helped along by subtle competitive signals they receive from other participants.

Tips and advice for your own life

Once you put a plan into action, it's easy to create competitive motivations. Our study offers an easy-to-follow template for doing this. “Health buddy” networks can be created by using any online platform where people can use an interface to record their program progress, or daily exercise activity, and compare themselves to others. Interestingly, one thing that we found most striking about the positive impact of social comparison is that the most successful participants in our study did not even have any social media tools for talking to each other: We only gave these participants the "bare minimum" exposure to their peers’ profile information and their daily records of activity. Even without any communication technology or interaction, social comparison among peers was enough to increase exercise rates by nearly 100 percent.

In How Behavior Spreads, I show that this social comparison effect works equally well to improve exercise levels regardless of whether people are put onto groups that compete with other groups, or whether people act as individuals competing with other individuals. From yoga to weight lifting to spinning, the dynamics of social comparison work the same way for groups and for individuals. What matters most for increased performance is that people can evaluate themselves against an “outgroup” of comparable peers.

References

Centola, Damon. 2018. How Behavior Spreads: The Science of Complex Contagions. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Zhang, Jingwen et al. 2016. Preventive Medicine Reports. “Support or Competition? How Online Social Networks Increase Physical Activity: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” (4): 453-458.