Empathy

The Difference Between Empathy and Sympathy

One often leads to the other, but not always.

Updated June 24, 2024 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Key points

- Sympathy is a reaction to the plight of others.

- Empathy means sharing another person's emotions.

- Compassion is more engaged than simple empathy.

In 1909, the psychologist Edward Titchener translated the German Einfühlung [‘feeling into’] as ‘empathy’. At that time, German philosophers discussed empathy in the context of artistic or aesthetic evaluation, but Titchener proposed that empathy can also help us to recognize one another as minded beings. Today, empathy might be defined as a person’s ability to identify and share in the emotions of another person, fictional character, or sentient being. Empathy involves two things: (1) seeing another person’s situation from their point of view, and (2) feeling, to a greater or lesser degree, the same emotions as they are feeling.

For me to share in another person’s point of view, it is not enough merely to put myself into her position or situation. Instead, I must go further still and imagine myself as her, and, more than that, imagine myself as her in the situation in which she finds herself. One cannot empathize with an abstract or detached feeling, but only with a particular person. To empathize with this person, I need to have some understanding of who she is and what she is doing, or trying to do. I need to have some idea of where she came from and where she wants to go. As John Steinbeck (d. 1968) wrote, ‘It means very little to know that a million Chinese are starving unless you know one Chinese who is starving.’

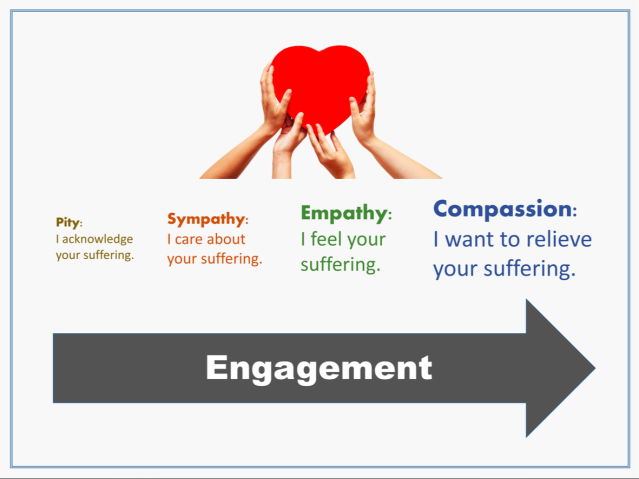

Empathy is easily confused with the likes of pity, sympathy, and compassion, which are all also prosocial reactions to the plights of others. Let’s look at each one in turn. Pity is a feeling of discomfort at the distress of one or more sentient beings, and usually carries paternalistic or condescending overtones. Inherent in the notion of pity is that its object does not deserve its plight, and is incapable of preventing or overturning it. Pity is less engaged than sympathy, empathy, or compassion, amounting to little more than a conscious acknowledgement of the plight of its object.

Sympathy [Greek, ‘fellow feeling’, ‘community of feeling’] is care or concern for someone, often someone close or relatable, accompanied by a wish to see them better off. Compared to pity, sympathy implies a greater sense of shared similarities and deeper personal engagement. But unlike empathy, sympathy does not involve a shared perspective or shared emotions, and while the facial expressions of sympathy convey caring and concern, they do not convey shared distress. Sympathy and empathy often lead to each other, but not always. For instance, it is possible to sympathize with a hedgehog, but not, strictly speaking, to empathize with it. Conversely, psychopaths with absolutely no sympathy for their victims can nonetheless make use of empathy to ensnare and torture them. Sympathy might also be distinguished from benevolence, which is a much more detached and impersonal attitude—akin to the attitude that I might have towards my students or neighbours, or that a monarch might have towards his or her subjects.

Compassion [Latin, ‘suffering alongside’], is more engaged than empathy, and is associated with an active desire to alleviate the suffering of its object. With empathy, I share your emotions; with compassion I not only share your emotions but also elevate them into a universal and transcending experience. Compassion, which builds upon empathy, is one of the main motivators of altruism.

Read more in Heaven and Hell: The Psychology of the Emotions.

Facebook image: Drazen Zigic/Shutterstock