Depression

Think You Can't Change Negative Behavior?

Just do more of what is already working.

Posted November 23, 2022 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- We often think that our problem behaviors are with us all the time.

- So it is helpful to notice circumstances when we didn’t behave in a negative or unhelpful way.

- Identifying what we did differently on those occasions—and why—can lead to positive change.

“Look!” said Suzanna, holding out a shaking hand. “It’s always like that. I’m always shaking. And I feel these terrible butterflies in my stomach all the time, too.”

“That must be awful,” I said, filing away the information. We had only just started our first session, and I didn’t intend to challenge her “always” at that point. I listened as she told me about her difficult upbringing and how she felt she fell below the expectations her parents had had of her, leading her to question her abilities. Too daunted to train as a teacher, she even lacked confidence in herself as a teaching assistant, causing the high stress that led her school to send her for counseling.

I asked if she had any hobbies or special interests, and her face immediately brightened as she talked about her love of taking photographs of flowers and animals.

“That must be very challenging for you,” I said.

She looked at me, puzzled.

“With your hands shaking with anxiety, as they do?” I prompted.

A look of sudden understanding flashed across her face. “They don’t shake when I’m taking photos,” she said. I was able to explain that when she was fully absorbed in something she loved, she had no need for anxiety. It was only when she questioned herself and listened to her negative self-talk that all the shaking happened. This was revelatory to her.

I asked about other times when she was doing something she loved, and it emerged that she was passionate about her role in the school and enjoyed helping the children to learn. Our work was to help her to trust in her abilities at school, just as she trusted them in photography. (And later, she did decide to train as a teacher.)

It can be a key moment in therapy when a person realizes that they don’t always behave in the globally negative way that they imagine. I had one client with whom I sometimes used to go on "therapy walks," accompanied by a neighbor’s delightful dog. On one occasion, the client was insisting that she could never get negative thoughts about herself out of her head, even though she tried the various techniques we had rehearsed.

As she was saying this, the dog suddenly took off after a baby squirrel and stretched out a paw to cuff it. We both stared, horrified, at the now dead baby creature, and then, determined to draw some good out of this sad scene, I said to my client, “You aren’t thinking about yourself now, are you!”

There are always exceptions to what we think of as fixed.

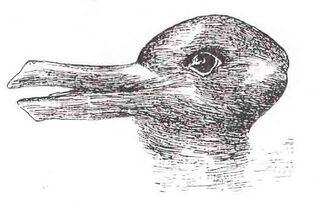

When I asked another client about a time when she had enjoyed herself recently, she told me about an engagement party she had attended but was quick to add that, even then, she was still depressed underneath. “If you were having a lovely time, you were not depressed,” I told her and showed her the image of the duck that is also a rabbit (see left).

“You can see one or the other, perhaps in very quick succession, but you can’t see both at the same time,” I told her. “When you were enjoying yourself, you were truly enjoying yourself. It was only when you detached yourself that you thought your depressive thoughts again.” The understanding that she had a choice about where to direct her attention and that she didn’t have to be controlled by depression was the turning point for her.

“When doesn’t it happen?” is an important question in therapy.

In an article in Human Givens Journal, therapist Dan Evans described his work with parents struggling to cope with their children’s behavior.1

One mother complained that her young son rarely got out of bed in time for school. Drilling down into this, Dan helped her recognize that the days he did get up in time were the days when she had to get to her part-time job. And what was different about those days was that she spoke in an authoritative voice because she was scared that, if late for work, she would be sacked. Once she started using her assertive voice every day, her son got up.

Another mother whose daughter, Jenna, was behaving badly at school told Dan that Jenna always behaved badly. When pressed to think of exceptions, she realized that Jenna behaved well with her grandparents. And pressed further to wonder why, she recognized that her parents praised her daughter for any efforts she made, whereas she herself was so worried about Jenna’s bad conduct that she focused only on what wasn’t good enough.

So sometimes change is easier than we think. If you worry about some aspect of your behavior but think it is too hard or too late to start doing something entirely different, perhaps you don’t have to. Perhaps you just need to do more of what is already working right.

References

1. Jones, D (2012). “And what happened next?” Human Givens Journal, 19, 2, 34–39