Intelligence

Lessons on Overcoming Adversity from Marie Curie

Think you have it bad? Consider what this great scientist endured.

Posted November 14, 2020 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Marie Curie is one of the greatest scientists in history—the first woman to be appointed a professor at the University of Paris, the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, the first person to win two Nobel Prizes, the only person to win Nobel Prizes in two different natural sciences, and the central member of a family that won a total of six Nobel Prizes. At a time when the pandemic is closing schools, her story offers insight and inspiration to students and would-be scientists around the world.

Born in 1867 in Warsaw, Poland, Maria Skladowska was the youngest of five children. Her parents were teachers, but one of her sisters and her mother died when she was young. Although an excellent student, the universities were closed to her, and she and her sister Bronya found it necessary to travel to Paris to get an education, each working to support the other.

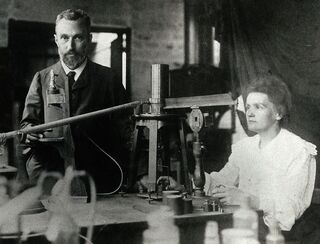

It was there that Maria, who continued to excel in school, changed her name to Marie and first met Pierre Curie, a young physics instructor. They were brought together as much as anything by their shared passion for science, and they wed in 1895. After they returned from their bicycling honeymoon, Marie continued to wear her blue wedding dress as her laboratory uniform.

The Curies investigated a new physical phenomenon that Marie would label “radioactivity,” the emission of energy by elements despite the absence of any chemical reaction. Using instruments devised by Pierre, she identified two new elements, one that for obvious reasons she called Radium and the other Polonium, after her motherland.

Marie also gave birth to two daughters, one named Irene, who would follow her parents into science and eventually garner a Nobel Prize with her husband for work on nuclear reactions. The younger daughter, Eve, would eventually write the best biography of her mother and marry a United Nations official who would win another Nobel Prize for work with UNICEF.

The Curies received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1903, which brought worldwide notoriety and a flood of requests for speeches, public appearances, and commercial endorsements. The Curies treated nearly all such requests with disdain, wishing only to be left alone to continue their scientific research, their great shared passion in life.

Pierre’s health had begun to decline, perhaps because of his work with radioactive elements, and in 1906 he was killed when he slipped on wet pavement and was struck by a horse-drawn cart. Marie sunk into deep despair from which she never fully recovered. Within a month, the University of Paris offered her the chair that had been created for Pierre, and she accepted.

She later founded the Radium Institute, created within the Pasteur Institute, named for another famous French scientist. In 1911, despite her worldwide fame, she was denied membership in the French Academy of Sciences, reflecting the concern of many members that admitting a woman would permanently alter the organization’s culture.

That same year, it was publicly revealed that Marie was romantically engaged with another great French physicist, Paul Langevin, who happened to be a husband and father. The scandal provoked wide outrage, and her heart was again broken when Langevin’s wife precipitated an end to their affair.

In 1911 Marie received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of two chemical elements, and she soon became the director of the Radium Institute. She had elaborate plans for its scientific program, but they were interrupted by World War I, which brought a halt to all research. Marie wished to be of service to her adopted country but did not know how to proceed.

At first, Marie thought of giving money to the French forces. She made plans to donate both her Nobel Prize money and gold medals to the war effort, but French bankers refused to melt down the medals, saying that they were too important to French history. She knew that the money would likely be lost but donated everything she could, longing for some more direct way of serving the war effort.

She knew that x-rays, which had been discovered by Wilhelm Roentgen the same year she and Pierre were wed, could help to diagnose soldiers’ injuries and illnesses. Despite opposition from the French military, she began procuring x-ray machines and vehicles to build a mobile x-ray service. Assisted by Irene, she created a fleet that eventually performed over one million x-ray examinations per year.

After the war, Marie continued her scientific work. Like most countries in Europe, the war had left France devastated, and Marie traveled to the US to raise funds. During this time, she met with many American leaders, including President Warren Harding. Eventually, Marie’s health began to fail, perhaps due to radiation exposure, and she died in 1934 at the age of 66.

The story of Marie Curie offers vital insights especially timely in the midst of a worldwide pandemic. She was discriminated against because she was Polish and a woman. She suffered numerous deep personal losses. She witnessed firsthand one of the most devastating wars in human history. But she treated every disappointment as an opportunity and always sought out some means to serve.

In her daughter’s biography, Marie is quoted as saying, “Life is not easy for any of us. But what of that? We must have perseverance and above all confidence in ourselves. We must believe that we are gifted for something, and that this thing, at whatever cost, must be attained.” Marie was remarkably gifted, but even more important, she never lost her determination to bring those gifts to full fruition through service to others.

References

Gunderman R. Marie Curie. London, Welbeck, 2020.