Ethics and Morality

As Elections Near, How Dilemmas Distort Ethics and Politics

Binary thinking can undermine choice, relationships, and true priorities.

Posted October 30, 2019 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

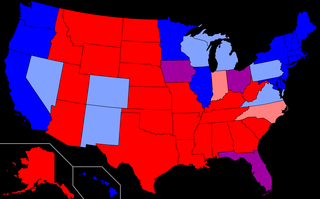

Whether in the popular press or the classroom, contemporary discussions of ethics and politics often revolve around dilemmas: Do you support candidate A or candidate B? Are you pro-choice or pro-life, for or against capital punishment, Democrat or Republican? It sometimes seems that important questions offer two and only two sharply opposed responses. But real life isn't so simple.

The word dilemma comes from the Greek, meaning “two premises.” Consider, for example, the famous dilemma at the heart of William Styron’s novel, Sophie’s Choice: When Sophie and her two young children arrive at the Auschwitz concentration camp, she is presented with a terrible decision: She can choose which child will be sent to the gas chamber and which to the labor camp, or both children will be gassed. This, we might assume, is ethics at its most robust.

In fact, nothing could be further from the truth. Dilemmas are more likely to represent exceptions than rules, and too often they function as smoke screens, hiding additional choices, polarizing relationships, and distracting us from the questions that really need to be asked.

Range of Alternatives

It is tempting to suppose that every situation can be boiled down to just two options: "like" or "dislike," thumbs up or thumbs down. For one thing, it seems to bring clarity to a world that can seem bewilderingly complex. But the ethical and political domains of life are not composed of binary choices.

Many dilemmas are false ones. Consider the proposition, "You either want better schools and support a tax increase or you don't." In fact, there may be other ways to improve schools that do not involve taxes at all, such as building learning communities among educators, and merely raising taxes may not necessarily enhance educational quality. Most situations in real life present more than just two straightforward alternatives, and it often takes curiosity and imagination to discern them.

Those who seek to reduce moral choice to simple forks in the road often do so because, by positing their own perspective as one of only two options, they hope to increase their chances of being chosen.

Effects on Relationships

Thinking in binary terms can also lead decision makers to write off persons or whole groups prematurely. Knowing where someone stands on a single issue — gun control, abortion rights, climate change — often provides surprisingly little insight into who they are and how they see the world. There is only so much we can glean from a lapel button or a soundbite.

Admittedly, when two people on opposite sides of an issue talk with one another, it may merely heighten their antipathy. But to dismiss or even demonize those who see things differently undercuts the possibility of engagement, foreclosing the possibility that they could get to know and learn from each other. It may even slam the door shut on a burgeoning friendship.

Polarization is useful if the goal is to vilify and condemn, but not when the goal is to engage, learn, and build relationships.

Answering the Wrong Question

A third problem with a dilemma-based approach to ethics and politics has to do with the way questions are put. No matter how good the responses, if decision makers address the wrong questions, the answers will be wrong. In the words of Thomas Pynchon, "If they can get you asking the wrong questions, they don't have to worry about the answers."

It doesn't matter what channel viewers turn to if watching television is not the appropriate focus. Likewise, choosing between two candidates in an election is important, but other questions may require more urgent attention: What are citizens doing to stimulate civic conversation, promote the vitality of communities, and create the conditions under which the republic is likely to flourish?

Dilemmas can blind decision makers to less immediately apparent but far more momentous matters. To avoid the pitfalls of shooting from the hip, it is often necessary to pause, step back, and ask good questions. Otherwise we fall prey to H. L. Mencken's prophecy — by mistaking complex problems for simple ones we end up with solutions that are neat, simple, and wrong.

Aristotle's Perspective

Aristotle, perhaps the most influential person in the history of Western civilization, understood this better than anyone. His masterpiece, the “Nicomachean Ethics,” perhaps the greatest work of philosophical ethics ever composed, is completely devoid of dilemmas. He focuses not on hard choices but on building character.

Aristotle's goal is not to tell readers what to choose but to help them develop into good human beings who can discern what is really at stake in each situation, frame the full range of choices appropriately, and move forward with wisdom. There are good people on both sides of just about any divide, and in most cases the most important ethical and political challenge is to maintain an open mind long enough for that goodness to become apparent.

Sophie's Choice notwithstanding, to treat ethics and politics as composed of dilemmas is to render life simplistic, superficial, and even alienating. Much of the time, dilemmas function in moral reasoning as junk food does in nutrition. They are not the nourishing core of a wholesome ethical and political diet but guilty pleasures, and as Aristotle might say, not the sort of fare on which robust characters and communities thrive.