Friends

How Children's Vision Differs From Adults'

There is no seeing without looking.

Posted August 12, 2022 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- Seeing is not a passive process. We must learn how to move our eyes to see.

- A child's view of a painting gives us insights into how he or she sees.

- The balance between central detail and peripheral layout develops with experience.

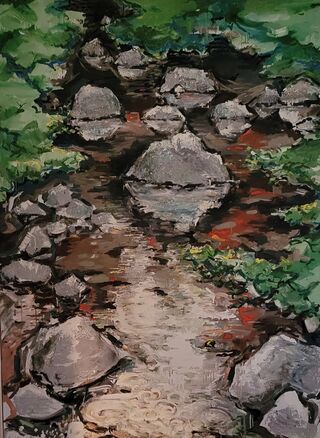

When two three-year-old children came to dinner, I finally had the opportunity to ask them a question I’ve been anxious to ask: What do young children see in my father’s paintings? In our dining room was a large (69 by 57 inch) painting of a brook.

“It’s water,” said one of the children. The other added, “There are rocks in the water.” They were not confused by the shapeless images of the plants or the reflections of the rocks in the water. Indeed, the reflections may have helped them see the water.

But then we moved into the kitchen where they saw another large (67 by 51 inch) painting. This one was of trees in fall:

But neither child saw the trees. One said the painting was “lots of colors.” Why did the kids not see the trees? Both lived in areas with beautiful fall foliage so they already had experienced plenty of views of colorful autumn leaves. The explanation may have to do with the way they looked at the painting.

In 2017, several vision scientists examined the way children and adults looked at five paintings by Vincent Van Gogh on display in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. As the participants gazed freely at the paintings, their eye movements were measured. In their initial views, no instructions were given to the subjects about what they would or should look at or see. The children in the study were 11 years old, much older than my two three-year-old guests, but, nonetheless, there were differences in their eye movements from those of the adults. The children, but not the adults, initially looked at the most salient parts of the paintings. Salient features are those that stand out, often because of their color or brightness, yet the most salient features in the Van Gogh paintings were not necessarily the most informative parts. If my three-year-old guests also focused on the most salient parts of my father’s tree painting, they would have concentrated on the bright oranges and yellows which produced amorphous shapes. They would have concluded, as one said, that the painting was “lots of colors.” In contrast, the brightest parts of my father’s brook painting were the heavily outlined rocks and the reflections in the water which provided lots of information about the watery scene.

In an older paper, noted psychologists, J.S. Bruner and N.H. Mackworth, compared the way adults and six-year-old children examined pictures. They reported that adults were more adept than kids at picking out the informative parts of the scene. But how do adults do that? Past experience plays a role, as well as the way the adults directed their eyes to look at the pictures. They scanned wider areas of the picture than the children. By moving their eyes back and forth across the same areas of the picture, they could compare and correlate different parts of the picture with each other.

Whenever my adult friends come to my house, they easily recognize and comment on my father’s beautiful painting of fall trees. Unlike the young children, none have trouble interpreting the scene. As they scan the canvas, they must pick up and follow the long dark lines that represent the trees. My very young guests may have gotten stuck on the bright colors and did not direct their eyes back and forth and up and down along the painting to correlate the different parts of the large canvas with each other.

These studies highlight an important challenge in vision. In order to understand a picture or a real-life landscape, we need to attend sufficiently to the details to recognize the objects in the scene, but we must also take in the wider view to understand the relationship of one object to another. This balance between central detail and peripheral layout develops with experience. Seeing is not a passive process. There is no seeing without looking. As we learn to look, we improve our ability to see throughout life.

References

Walker, F., Bucker, B., Anderson, N.C., Schreij, D., Theeuwes, J. (2017). Looking at paintings in the Vincent Van Gogh Museum: Eye movement patterns of children and adults. Plos One, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178912.

Mackworth, N. H. & Bruner, J. S. (1970). How adults and children search and recognize pictures. Human Development 13: 149-177.