Law and Crime

Harsh Justice

Why doesn't increasing the severity of punishment lead to less crime?

Posted September 13, 2015

As an ethicist, I think a fair amount about moral and political issues. One thing I’ve noticed is how often views on those issues really depend on claims of psychology—and if those psychological claims are wrong, it’s pretty likely that the moral and political view is mistaken too. Here I’d like to give one example of that.

In recent times, many people, particularly in the United States, have apparently believed that

Punishing criminals deters crimes—in fact, the harsher the punishment, the more it will deter crime.

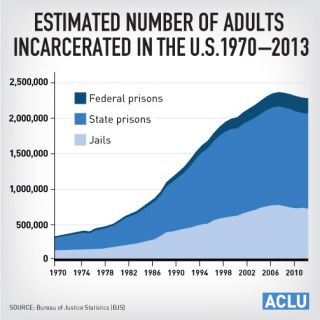

This widespread belief is reflected in the fact that, until very recently, a ‘get tough’ mentality dominated American political discourse surrounding crime. From the 1970s well into the 21st century, politicians risked little by advocating for longer sentences and harsher penalties. In advocating for harsh punishments, these leaders generally assured the public that tougher sentences meant less crime.

But that turned out not to be the case. Plenty of people went to prison and for longer stretches. And starting in the early 1990’s, crime began a two decade long decline that the public seems by and large not to have noticed. Yet there’s little evidence to suggest that the threat of punishment—even the threat of very harsh punishment, such as the death penalty—is responsible for the drop in crime. A massive 2014 study undertaken by the National Research Council announced that one of its “most important conclusions is that the incremental deterrent effect of increases in lengthy prison sentences is modest at best.” Put in less academic-ese: Threatening people with increasingly harsh punishments doesn’t discourage crime.

This means that the common view about punishment and deterrence—the view that led to huge increases in the U.S. prison population—is mistaken. But how do we explain this finding?

Many economists, philosophers, and criminologists have assumed that criminal behavior is self-interested, rational behavior—that in the end, people commit crime because, having weighed the prospect of being caught and punished versus the benefits of committing the crime, they conclude that the likely benefits outweigh the likely costs. Yet this assumption runs headlong into the fact that often enough would-be criminals either lack rational beliefs about their situation or struggle to act on those rational beliefs. Take a simple example: Do you happen to know what the punishment for arson is where you live? I bet you probably don’t. But notice that in order for a person to decide rationally whether to commit arson, she has to know what the punishment would be were she caught and convicted. And even if she does know the punishment (as well as the likelihood of being caught and convicted), a would-be criminal may simply not be thinking rationally at the time the crime is committed. She may be influenced by drugs or alcohol, motivated by rage or a desire for revenge, or suffering from a mental illness that leads her to think she is invincible or has nothing to lose. So even if a person has the beliefs necessary to make a rational decision about committing a crime, she may be unable to access or act upon those beliefs.

More generally, many have assumed that in making decisions, individuals rely upon expected utility. This is a somewhat technical notion, but the basic idea is that a person’s choice is rational if that choice generates the highest expected value to that person in comparison to the alternative options available to her. The expected utility of an outcome can be calculated as:

[Probability that the outcome will occur] x [Benefit or cost to the chooser of that outcome]

This formula tells us that it is very rational to choose a particular option if that option is very likely to result in an outcome that is very beneficial. Conversely, it becomes less rational to choose an option the less likely the preferred outcome will result by choosing that option or the less desirable the outcome would be. An example: If I have every reason to believe that eggnog will be served at my office holiday party and I really love eggnog, then going to the party is very rational when compared to most of the other options available to me (staying home to watch reality TV, say). But if I’m less sure there will be eggnog at the party, or I’m not so great a fan of eggnog, then it becomes less rational for me to attend the party.

How does this apply to the choice to commit crimes? If most of us chose on the basis of expected utility, then the common view about punishment and deterrence could well be true. After all, by imposing ever harsher punishments on people, we decrease the benefits (or increase the costs) of engaging in crime and so decrease crime’s expected utility. Suppose I dislike spending two years in prison twice as much as I dislike spending one year in prison. The common view would predict that, if the government doubled the punishment for arson from one year to two years, I would thereafter be half as likely to commit arson (assuming that it is not any more or less likely that I will be caught once the punishment is doubled).

But again, the empirical evidence suggests that stiffening punishments does not increase deterrence. My own conjecture is that we often do not calculate what is best for ourselves in exactly the way that the expected utility approach recommends. According to that approach, the probability of an outcome and how beneficial or costly it is to a person are independent factors in determining expected utility. They have nothing to do with one another. Furthermore, the expected utility approach does not give priority to one factor or the other in determining expected utility. Each factor is supposed to count equally in how we determine what it is rational for us to do.

Yet I imagine that many of us actually estimate our expected utilities in a sequential way. We first estimate how likely an outcome is, and then we only bother to consider how costly or beneficial the outcome is if we think the likelihood of the outcome is more than negligible. Put differently, if we judge that some outcome is pretty unlikely—effectively zero, we might say—we ignore how great the costs or benefits are. This has direct application to the decision to engage in crime. Consider the child deciding whether to steal a cookie from the family cookie jar. Doesn’t the child first calculate whether he’ll get caught, and if he sincerely believes it very improbable he will be caught, he then takes the cookie? Notice that this sort of reasoning entails that it doesn’t matter much how good (or bad) the outcome is. Likewise, in committing crimes, individuals probably don’t think too much about how bad it would be to be punished. After all, by committing the crime, they have likely already concluded that they won’t be caught and punished! That makes the severity of the punishment largely irrelevant to deterrence. A person doesn’t worry about how severe a punishment is if she is already convinced it won’t be inflicted on her.

At any rate, even if severely punishing people in order to deter crime would be ethically justified, to appeal to deterrence doesn’t seem sensible if increasing the punishments doesn’t decrease the crime. Here I’ve used some evidence from psychology, and some tools from economics and philosophy, to suggest why harsher punishments do not seem to have much deterrent impact: Very roughly, we are not as rational, or rational in precisely the ways we would have to be, in order for the common view to be true. The 18th century philosopher Cesare Beccaria hypothesized that whether punishment deters crime depends on its severity, certainty, and swiftness of imposition. If I am right, then perhaps our criminal justice system would be more effective if it concentrated on making punishment more certain and more swift rather than more harsh.