Dementia

Parlez-vous Dementia?

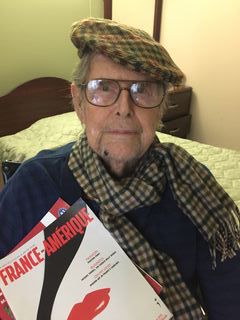

A father and daughter duel declining minds by declining French verbs together

Posted January 6, 2017

‘A different language is a different vision of life’— Federico Fellini

I think about this quote as I struggle with my 96-year-old father’s dementia. Over the last three years, as his mind has become increasingly ensnared by obsessions that rise up in the form of three repeated questions, I have discovered various ways to short-circuit the tedious loops of conversation: Reading aloud Shelley or Shakespeare; discussing his war experiences in New Caledonia and Bougainville; getting him to recount living in France during the Great Depression as a young boy.

Comme il faut! (As it should be!) C’est dommage! (It’s a pity!) Qui vivra verra! (Time will tell!)

My father’s speech, endlessly hyper-eloquent, has always been peppered with French expressions and chansons.

‘The first marine, he ate the bean, parlez-vous?’

That year in France made of him a life-long francophile; he returned to the states fluent in the language and a lover of baguettes, bastides, musées, Mer Mediterranée. Fromage et fruits!

They sailed on a transatlantic steamer in September of 1933—my father, his mother, his brother, his sister—a sixty-five passenger cargo ship that took fourteen days to reach Le Havre. My father and his siblings played shuffleboard for hours on the deck.

‘Ah, Madame Cormillet! Not a word of English was tolerated!’

Madame Cormillet was a retired Sorbonne professor, and when my father and his family moved into her pensione in Tours, they became totally immersed in French culture. Sink or swim. C’est la guerre!

My father’s stories about France enchanted me while I was growing up; because of them and his contagious reverence for the place and its people, I passionately studied French up through eleventh grade, after which I abandoned it to try Spanish.

Until about a year ago.

Listening to the familiar tales of that winter at the Hotel Rives d’Azur, Cap Martin in the background, and the incredible fact that my nonagenarian, demented father seemed to have retained much of his French, ignited in me a keen desire to revisit la langue française. I decided, at age 61, to begin studying French seriously, to possibly even become fluent.

I had travelled extensively in France over the years and developed an intense fondness for Southwestern France: Toulouse and the surrounding countryside of garlic farmers and artists continues to entrance me; I have enjoyed many happy summer weeks with dear friends who have settled there.

Beyond my deep personal connection to France, I was driven to sign up at the Alliance Française for lessons because I longed to be able to speak French with my father. I wanted us to have this very special thing that we could participate in together, something that would somehow lift us from the heartache and exhaustion of dementia.

The first class was daunting. The Alliance Française approach involves complete immersion and a method that relies on the IPA, or International Phonetic Alphabet, a system to represent sounds which is based essentially on the Latin alphabet. Here are a few examples: œ̃; ɔ̃; ʒ; ɛ̃; ʁ .

Upon viewing these symbols, one student immediately quit the course; the rest of us were feeling a bit anxious.

Our teacher, naturally—being French— was rail thin and effortlessly chic and utterly charming. She assured the three of us—all women, all not teenagers—that contrary to popular thought, middle-aged people can indeed learn a new language. This, she said, is because their life experience allows them to make strong associations to words.

I turned to William Alexander’s delightful book, ‘Flirting with French: How a Language Charmed Me, Seduced Me, & Nearly Broke My Heart’ for some additional reassurance.

Alexander embarks on a year–long journey in his late fifties to become fluent in French; at the end of it he discovers that, although he is not as proficient as he had envisioned, the act of attempting to conquer French has dramatically elevated his cognitive scores on a cognitive-function exam he took at both the beginning and close of his quest.

‘Studying French,’ he writes, ‘has been like drinking from a mental fountain of youth!’

This was the comfort I needed!

As I grappled with masculin ou féminin, I started to engage my father little by little with French. It became clear early on that we would not be able to sustain a conversation more complicated than ‘Where are you from and what do you like about it?’ My French was still very limited; his was a bit rusty.

But, something extraordinary happened when I opened my French workbook, ‘Version Originale’ and simply began going over some of the exercises with him. A rhythm emerged as we worked on my lessons together. We were spending our time in French, and though it was challenging, it was comfortable also. And it was thrilling; we could actually do this as father and daughter.

First we counted to one hundred in unison. ‘Cent! Très bon!’

We looked at a photograph of a French village and took turns naming the things that were there and not there.

‘Il y a une gare!’

‘Il n’y a pas d’église!’

We conjugate verbs. Être: je suis; tu es; elle est; nous sommes; vous êtes; ils sont. Irregular verbs—difficile!

We use my iPhone to listen to RFI, a French radio station; though we pick up snippets of the news, most of the reporters speak too quickly for either of us. Still, it is fun just hearing our beautiful, beloved French as it is spoken every day.

These recent months, as my father’s short-term memory has all but vaporized, and his long-term memory is sliding, I take enormous solace and pleasure from the sessions we spend practicing our French. In those magical hours, we travel to a sweet little sphere where dementia does not exist, where we are transformed into fresh versions of father and daughter, where we rediscover the past and reinvent the present and the future.

Stepping into a different language can make us more compassionate, more alert to what it means to be human, indeed provide us with a ‘different vision of life’.

And, as my father and I continue this way of communicating, I can feel our brains brightening, our minds opening, the earth expanding.

Incroyable!