Friends

How Do I Loathe Thee? Let Me Count the Ways

How people (and psychologists) talk about friends and enemies.

Posted August 27, 2021 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Language serves as a starting point for understanding personality.

- People use language differently when describing "liked" versus "disliked" others.

- Recent research demonstrates some interesting points of agreement and disagreement in personal descriptions.

Tolstoy famously suggested that all happy families were alike, and that unhappy families were unique in their discontent. I am frequently reminded of his famous statement when I conduct one of my standard ice-breaking activities in my Psychology of Personality course. I simply randomly assign students to describe either someone they like very much or someone who they do not like very much. I then compile lists of the adjectives and phrases that people volunteer, attempting to group them in sensible ways and make points about both what is and isn’t “personality” and the ways we might try to organize the concept.

A common theme is that the negative descriptions tend to be more nuanced and varied. A paraphrased example:

My ex-best friend is conniving, duplicitous, two-faced, and arrogant. She was rude to my other friends and said things to intentionally make me feel bad about myself.

On the other hand, many of the liked were described thusly:

I love my <insert familial here>. S/he is kind and caring and will do anything for me.

Obviously, as with anything, there is variance in the categories, with some positive descriptions being both specific and extensive, but the general rule is that we have more (and more unique) things to say about bad people and behavior. I was thus unsurprised when I saw that Daniel Leising and colleagues confirmed this with more sophisticated empirical techniques (Leising, Ostrovski, & Borkenau, 2012). I am delighted that this particular question and its accompanying methodology is becoming something of a mini-trend in the field (more on this later).

Relatedly, something that has been on my mind for a while now is how much my sub-discipline relies on the use of rating scales constructed to assess personality. Most readers have probably answered such a personality questionnaire, wherein you estimate, on a scale of 1-7 or 1-5, or 1-15 how “outgoing or sociable," “adventurous," or “worried” you might be, generally speaking. If you’ve been within 50 yards of me in the past 2 decades, you probably answered these questions about someone else, too!

Some of the questions I get during debriefing or during class when we discuss these measures are “Why do we only ask about these things?” “What about context?” “What does this word mean in this context?” and “What is a 4 out of 7 supposed to signify?” These are all good questions.

The irony is that our measures have their roots in natural language (Saucier & Goldberg, 1996). The search for structure in personality (i.e., how many traits are there?) often begins with a lexical approach—that is, we look to natural language use, such as terms listed in the dictionary, to develop a reservoir of possible ways that people differ. Two or three steps down the road is when the rating scales start being applied to these terms, which then become variables for increasingly complicated statistical analyses that yield our favored magic number of personality traits.

And this is a good and useful activity. The development of such measures has furthered personality science, in my opinion, and our little world would be worse without them. That said, they also can constrain and de-realize our attempts to study some aspects of personality.

To find out if married couples know each other, I direct them to identical questionnaires about themselves and their partner and then quantitatively compare these in various ways (e.g., Watson, Beer, & McDade-Montez, 2014). But I often wonder if these results are satisfying in terms of ecological validity, or the extent to which they mirror the phenomenon as it occurs naturally. In this case, does the quantitative index capture how well these two people know each other? If the number is higher, do they finish each other’s sentences at dinner parties or anticipate the exact gift that will brighten their day, or know the moments when it’s best to leave their partner alone (or not to)?

Study: Personality descriptions among best friends

I had actually been considering how to approach this problem in this fashion when I came across a recent paper from Dr. Jessie Sun and colleagues (Sun et al., in press), in which the research team gathered descriptions of the two best and worst traits about a person according to a) the person themselves and b) their friend. After this, a team of coders examined each response and classified them broadly in terms of their fit with standard models of personality trait structure (e.g., “enthusiastic” qualifies as Extraversion, “hard-working” as Conscientious). They then asked a few key questions about these responses. First, they replicated previous findings regarding the greater variation in negative descriptors: There was approximately a 50% increase in the number of novel terms produced in the worst trait category relative to best traits.

Second, they confirmed the intuitive theory that best traits would stick to desirable poles of traits and worst traits to undesirable poles. Generally speaking, Big Five traits have an end (pole) that seems more associated with positivity—for example, on average, it is seen as better to be more extraverted or emotionally stable than it is to be less of either. Free descriptions clung to that pattern, but not entirely. On some occasions, for example, traits marking desirable poles of traits ended up cited by friends as a worst trait (e.g. “loud” marking high Extraversion, “pushover” marking high Agreeableness). That particular pattern (high extraversion as a negative) was more commonly seen in peer-ratings versus self-ratings, so look out, extraverts—others may not always view the desirable pole as positive.

Finally, they also examined the extent to which descriptions by self and friends corresponded—did people’s thoughts overlap? When coded at the specific level (e.g., each member of the friendship dyad listed “enthusiastic” or a close synonym thereof as a strength of one of the individuals)—which best approximates our spontaneous descriptions (“my wife is fastidious”)—agreement was seemingly low. That is, two people spontaneously volunteered the same strengths and weaknesses about 10-20% of the time. However, these numbers improve when the terms are categorized more broadly by the researchers (“fastidious” coded as part of the larger category of Conscientiousness). I agree with the authors, however, when they claim that this is actually quite a feat—would your best friend come up with similar specific terms about your two best and two worst qualities?

Some other interesting things happened. For example, about 8% of people self-reported a best and worst trait in the same broad trait category—an implicit recognition of David Funder’s First Law (i.e., our greatest strengths are often our greatest weaknesses; Funder, 2019). Further, 10% of friends listed something as a worst trait that the individual had listed as a best trait (again, broadly speaking), and 5% did the reverse. That is, there were instances of one person say, citing “confidence” as a strength and their friend citing “arrogance” as their weakness, or of a person citing “shyness” as a weakness and their friend praising their ability to listen quietly.

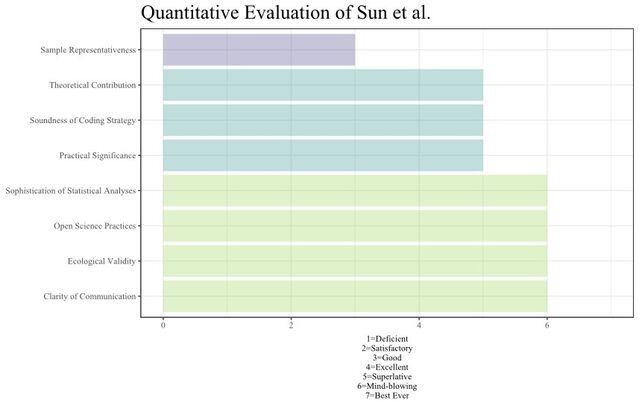

I have only hit a few highlights of this excellent paper, and I encourage you to read it in its entirety for lots more detail. Let me count the ways in which this was a cool study: It’s a broadly accessible topic with intuitive research questions that appeal to both scientists and non-scientists. It advances knowledge and theory, utilizes innovative and ecologically valid methods. It is clearly communicated and models the best of open science practices, and it features easily digestible and attractive graphical depictions of results. Or it was just “really great," I guess.

Returning to our initial premise, a final reason why we should celebrate this work is that it is actually quite difficult to go against our quantifying nature. In a recent lab meeting, I asked my students to help me generate a protocol for an upcoming study in which I want to gather open-ended descriptions of how people’s opinions of close others in their lives have changed over time. During the course of the meeting, we fiddled with various prompts and the phrasing thereof, providing our own answers and determining whether or not we could extract the truths we hoped from such methods. With each modification and specification, we got closer to something we felt like could work with, and when I summarized our discussion in a subsequent document, it basically consisted of a set of rating scales. I will lace up my nerd boots, re-consult Dan McAdams’s lab’s long-running tradition of expertly employing narrative approaches to understanding personality, and try again. Sometimes my work is good, and other times it is shallow, vague, unreliable, ill-considered, vapid, intellectually offensive, juvenile, trivial, trite, arcane…

References

Funder (1997). The Personality Puzzle. W.W. Norton & Co.

Leising, D., Ostrovski, O., & Borkenau, P. (2012). Vocabulary for describing disliked persons is more differentiated than vocabulary for describing liked persons. Journal of Research in Personality, 46, 393–396. doi:10.1016/ j.jrp.2012.03.006

Saucier, G., & Goldberg, L. R. (1996). The language of personality: Lexical perspectives on the five-factor model. In J. S. Wiggins (Ed.). The five-factor model of personality: perspectives (pp. 21–50). New York: Guilford.

Sun, J., Neufeld, B., Snelgrove, P., & Vazire, S. (in press). Personality evaluated: What do people most like and dislike about themselves and their friends? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. https://psyarxiv.com/4sgna/

Watson, D., Beer, A., & McDade, M. E. (2014). The role of active assortment in spousal similarity. Journal of Personality, 82, 116–129. https://doi-org.uscupstate.idm.oclc.org/10.1111/jopy.12039