Identity

How Disability Pride Fights Ableism

Reflections on the 30th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Posted August 10, 2020 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

This year is the 30th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the landmark civil rights law for people with disabilities. The ADA was signed into law thanks to a visionary group of disability rights activists who had the radical notion that disabled people were a minority group who deserved civil rights.

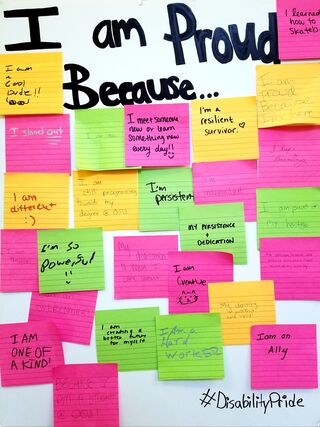

Although disability pride undergirded the disability rights movement leading to the ADA, 30 years later, it is still rare. The ADA promises equal access to public spaces, transportation, and employment, but implementing these rights is still imperfect and too often happens on the backs of disabled people. A disability pride movement will shift our culture and subvert ableism, or disability discrimination.

Disabled people have a lot in common with other minorities, including disparities in civil rights, income, education, and health, and underrepresentation in media and politics. Like pride movements for other minority groups (e.g., gay pride, Black pride), disability pride is designed to subvert what has been a very stigmatized identity. If feeling pride about one’s disability sounds odd (or even like an oxymoron) to you, consider that gay pride, for example, was a foreign concept to the public before the massive shift in public opinion and civil rights it engendered.

People with disabilities are the largest minority group in the United States, making up 26 percent of the population. Thirty years after the ADA was passed, many are still not aware that it protects people with any substantial impairment, whether or not that impairment falls into society’s stereotype of what a disability looks like. This includes people with physical impairments, significant mental illness, invisible chronic health conditions, and many more.

In a series of studies, my colleagues and I conducted a survey of factors related to disability identity and disability pride. The first study surveyed 1,105 adults online. Of those people, 710, or 64 percent, indicated they had any type of health condition or impairment. Of the 710 people who had health conditions, only 12 percent of people agreed or strongly agreed that they considered themselves to be a person with a disability. Experiencing stigma was the strongest predictor of identifying as disabled. Stigma is considered by many disability scholars to be the primary cause of disability, and our study suggests it also plays a role when people think about their own identities.

In the second study, we examined more questions from the sample of 710 people with impairments. Participants answered questions from a disability pride questionnaire developed by Dr. Rosemary Darling. The questionnaire included items such as: “I am proud of my disability,” “I am a better person because of my disability” and “my disability enriches my life.” We found that disability pride was rare in our sample, but those who had social support were people of color, and, once again, who experienced stigma, were more likely to feel disability pride. Experiencing stigma was associated with greater disability pride, and in turn, greater pride was associated with greater self-esteem. Disability pride functions as a way for disabled people to protect their self-esteem against ableism.

Other research I’ve conducted indicates that disability identity is associated with a variety of psychological benefits, such as lower depression and anxiety among people with multiple sclerosis. Compared to people who acquired mobility disabilities at some point after birth, people who were born with mobility disabilities have higher satisfaction with life, and this may be driven by a positive disability identity and self-efficacy to manage their disability. I suspect this is because people with congenital disabilities go through their initial development learning about themselves and the world alongside their disability. In comparison, people who acquire disabilities must relearn how to navigate the world and often report feeling a loss of identity.

Building disability pride

What can you do to foster disability pride throughout the 30th anniversary of the ADA and create a new generation of disability rights?

The value of “coming out” proud

Why is disability pride still rare? The majority of disabilities are invisible and people have to choose to disclose them. To avoid the very real possibility of discrimination, many people avoid disclosing or even conceal their disabilities. But not identifying perpetuates the idea that disability is an undesirable and uncommon experience.

“Coming out” as disabled and expressing disability pride offers some protection against the negative psychological effects of stigma. One reason is that it helps people find others who share their identities or allies to support them. When people with invisible disabilities disclose, they sometimes discover that friends they have known for years share their identities.

Coming out also has the power to change society’s views about disability. Expressing pride will show society how common it is to experience disability and that so many valued members of the community are touched by it. Chances are, about 26 percent of your neighbors, co-workers, friends, and family members have a disability. Coming out increases representation in the media and politics so disabled voices are recognized. Once a critical mass of people come out as disabled, it won’t seem as risky to disclose a disability. But lots of brave people will need to risk discrimination when coming out to get to us to that point.

Think beyond the diagnosis

Research from Dr. Arielle Silverman finds that disabled people have better life satisfaction if they are friends with even one other person with a disability. Cross-impairment friendships can provide solidarity. Think beyond a specific diagnosis. People with diverse conditions may have different medical symptoms but shared societal barriers. The ADA became law because activists with many different impairments worked together for the greater good. We must continue to forge these alliances to fight ableism.

There is much more to say about disability pride, language, and ableism. Stay tuned for future posts on these topics.