Suicide

Silence About Suicide Is Killing Us

To end suicide, people must feel safe talking about suicide.

Posted September 8, 2024 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- Suicide is a leading cause of death.

- Suicide is still a taboo and uncomfortable topic for many people.

- We cannot stop suicide if people do not talk about suicide.

September is Suicide Awareness Month, a time that hits all too close to home for me. In 2017, I lost my older brother, Matt, to suicide. Matt was only 27 years old, and I miss life with him.

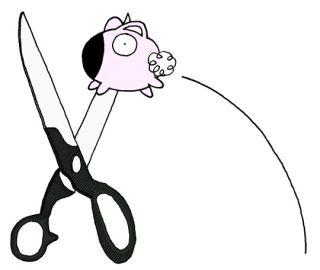

As a suicide loss survivor, I feel conflicted talking about my brother’s passing. I never want his memory to be defined solely by this tragedy. Matt was an impressively unique and amazing person. Among his loved ones, his creative personality and unmatched dry sense of humor are his defining gifts. Just see for yourself in the comic, below. Matt’s artwork somehow captures a sense of tragedy and whimsy in one illustration. Of course, Matt was also so much more.

Why I Talk About My Brother's Suicide

But here’s why I continue to talk openly about how we lost my brother. In the United States, suicide is among the top 10 leading causes of death for people aged 10-64 years. Suicide is the second-leading cause of death for age groups of people between 10-14 and 25-34. In 2022, an estimated 1.6 million people made a suicide attempt, and 49,476 people died by suicide.

The enormity of suicide on a personal and societal scale is tragic. And yet, in my experience, most people do not talk about suicide, even when it is relevant to their lives or their loved ones. And most people do not know how to talk about suicide effectively. Mentioning the topic itself can create a feeling of tension and discomfort, so much so that people might entirely avoid speaking about it.

As we know from psychology, the avoidance of a problem may feel better in the short-term, but it can hurt badly in the long-term. Below, I share how silence about suicide can hurt different stakeholders.

1. People with suicidal thoughts

One way to prevent suicide is to identify who is having suicidal thoughts, and then support them in getting help. This approach sounds straightforward: Let’s say our friend notices they develop a discolored, abnormally shaped mole. We hope our friend will speak up about it, so we can support them in getting screened for skin cancer. With suicide, however, people with suicidal thoughts might not feel safe talking about the topic.

Research shows that many people will hide their thoughts of suicide because they are concerned about being negatively evaluated (Hom et al., 2021; Maple et al., 2020). This makes sense. When no one talks about a subject, our minds start to perceive this uncertainty as a threat. People might think, “If people aren’t talking about suicide, then maybe it’s not okay to talk about suicide.” People with suicidal thoughts might also feel like they will be viewed as “weak,” “overreacting,” “attention-seeking,” or “not serious.” I have had patients share with me that they’ve been told such invalidating statements to their face. Sadly, I’m never surprised.

When my brother talked openly about having suicidal thoughts, I remember some family members did not believe him. Or, perhaps, they did not believe the level of pain my brother was experiencing. My family’s reaction did not surprise me because suicide is not yet a normalized topic of conversation; there is no social script for helping our loved ones cope with suicidal thoughts. But because people did not know how to talk about suicide, my brother began to hide his pain.

2. Suicide loss survivors

Losing a loved one to suicide is one of life’s most painful experiences. For each suicide, there are on average 135 people who are affected by the tragedy (Cerel et al., 2019). It is common for survivors to face bereavement challenges that differ from those following other types of death. Research shows that survivors often have feelings of shame, embarrassment, and “being tainted” following a suicide (Hanschmidt et al., 2016). Many survivors also feel alone, misunderstood, and avoided by their social networks after the tragedy.

From my own experience, I certainly have felt uncomfortable and misunderstood as a suicide loss survivor. I am not embarrassed. I am not ashamed. But I do feel like the room gets colder when I say the word “suicide.” People have shared with me that I am “brave” for speaking up about suicide, but this well-meaning compliment just illustrates the persisting stigma around suicide. If talking about suicide was more normalized, then there would be no reason to call me brave. We must learn to talk about suicide to support our loved ones who have lost someone to this tragedy.

3. Broader society

Suicide is not an individual problem; it is a public health concern that requires efforts at the individual, community, and legislative levels. But if individuals do not talk about it, then policy makers will not care about it. Fortunately, there has been great progress in suicide awareness over the past 2 decades. Since 2005, the United States has launched a national crisis line (“Dial 988”), declared September as Suicide Awareness Month, and coordinated national strategies to aid suicide prevention efforts (SAMHSA, 2024). These are huge accomplishments that show the power of advocacy.

However, there is still so much to be done. Research shows that Americans continue to face significant barriers in affording and accessing mental health services (Coombs et al., 2021; Walker et al., 2015). Studies also show that there is an unmet need for workplace accommodations among people with mental health conditions (McDowell & Fossey, 2015). Ultimately, preventing suicide will require ongoing advocacy efforts to talk about suicide.

Important Disclaimer

I want to clarify my stance: I do not think everyone should talk about suicide all the time, in every context. Talking about suicide irresponsibly can actually have harmful effects, such as when the media covers a suicide without following appropriate reporting guidelines (Niederkrotenthaler et al., 2020). The spirit of this post is to encourage having more effective conversations about suicide—conversations that minimize the chance of harm, while increasing the chance of good outcomes.

Tips for Talking About Suicide

In later posts, I will get deeper into the how and when to talk about suicide. For now, here are some quick tips and resources for talking about suicide with a loved one.

- Actively listen to their story.

- Create a sense of safety.

- Demonstrate that you are hearing their story with your words and actions.

- Be non-judgmental and open-minded toward their experience.

- Provide validation and support.

- Communicate that you care.

- Offer assistance in getting them help.

Using these skills is easier said than done, but I’m hopeful we can all do it.

If you or someone you love is contemplating suicide, seek help immediately. For help 24/7 dial 988 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, or reach out to the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741. To find a therapist near you, visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

References

Administration (SAMHSA), S. A. and M. H. S. (2024, April 15). 2024 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention [Text]. https://www.hhs.gov/programs/prevention-and-wellness/mental-health-subs…

Cerel, J., Brown, M. M., Maple, M., Singleton, M., van de Venne, J., Moore, M., & Flaherty, C. (2019). How Many People Are Exposed to Suicide? Not Six. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 49(2), 529–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12450

Coombs, N. C., Meriwether, W. E., Caringi, J., & Newcomer, S. R. (2021). Barriers to healthcare access among U.S. adults with mental health challenges: A population-based study. SSM - Population Health, 15, 100847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100847

Hanschmidt, F., Lehnig, F., Riedel-Heller, S. G., & Kersting, A. (2016). The Stigma of Suicide Survivorship and Related Consequences—A Systematic Review. PLOS ONE, 11(9), e0162688. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0162688

Hom, M. A., Bauer, B. W., Stanley, I. H., Boffa, J. W., Stage, D. L., Capron, D. W., Schmidt, N. B., & Joiner, T. E. (2021). Suicide attempt survivors’ recommendations for improving mental health treatment for attempt survivors. Psychological Services, 18(3), 365–376. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000415

Maple, M., Frey, L. M., McKay, K., Coker, S., & Grey, S. (2020). “Nobody Hears a Silent Cry for Help”: Suicide Attempt Survivors’ Experiences of Disclosing During and After a Crisis. Archives of Suicide Research, 24(4), 498–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2019.1658671

McDowell, C., & Fossey, E. (2015). Workplace Accommodations for People with Mental Illness: A Scoping Review. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 25(1), 197–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-014-9512-y

Niederkrotenthaler, T., Braun, M., Pirkis, J., Till, B., Stack, S., Sinyor, M., Tran, U. S., Voracek, M., Cheng, Q., Arendt, F., Scherr, S., Yip, P. S. F., & Spittal, M. J. (2020). Association between suicide reporting in the media and suicide: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 368, m575. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m575

Walker, E. R., Cummings, J. R., Hockenberry, J. M., & Druss, B. G. (2015). Insurance Status, Use of Mental Health Services, and Unmet Need for Mental Health Care in the United States. Psychiatric Services, 66(6), 578–584. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400248