Mating

How Much Our Partner Preferences (Don't) Really Differ

Surprisingly steady attractions, over time and cultures.

Posted December 19, 2023 Reviewed by Ray Parker

Key points

- Mate preferences are not entirely subjective; patterns exist in human desires.

- Research reveals consistency, particularly for traits like kindness and intelligence.

- Over time and across cultures, mate preferences are often rigid, reflecting our evolved mating psychology.

A myth I like to bust early on in my evolutionary psychology lectures is the idea that mate preferences are unique to each person and that everyone wants different things. For every person who wants a physically attractive partner, there's another who could take it or leave it.

But how much do mate preferences actually vary from person to person? Well, let's look back at one of the seminal papers on mate preferences spearheaded by David Buss in 1990. In this paper, over 9,000 people from 37 countries ranked the importance of 13 traits, from creativity to kindness, with one being the most important and 13 being the least important.

Forget the average; let's look at the variability.

Normally, when reading studies like this, people tend to look carefully at the averages to see which traits rank the highest. (It's kindness and understanding, by the way. You can read more about why in my post here.) But today, I want to draw your attention not to the average but to the other number that tends to accompany it—the standard deviation (SD).

The SD measures how much variability exists among people's answers. Small numbers mean that people are answering in a fairly consistent way and that the average tends to represent the choices of many people. A large SD is the opposite.

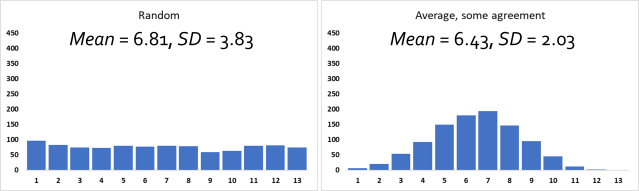

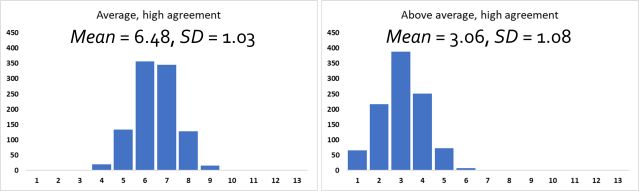

Say a group of participants ranked 13 traits for their importance, and we wanted to see how consistently they ranked one of them, intelligence. On the left-hand side of the figure below, you can see what we'd expect to happen if people's ranking of intelligence was random; just as many people would assign it a rank of 1 as those who would give it 12 or 13. The result? An average score is somewhere in the middle and a standard deviation of around 3.8.

That number becomes our magic number here because an SD lower than this would mean that people were becoming less random and more consistent in their rankings.

On the right-hand side, you can see what happens when the average response is about the same, but the SD lowers to 2. Now, most people rank intelligence a few points on either side of the mean, and very few are at the extremes—ranking it as 1 or 13.

What happens when we go even lower, for example, to an SD of 1? Then things get even tighter. If intelligence were given a rank between 6 and 7 on average, few people would stray from this. A small number might rank it 5 or 8, and a tiny fraction 4 or 9, but 1-3 and 10-13 would seldom happen.

Variability in real mate preferences

Enough of the hypotheticals. What does this look like when people actually rank traits? Well, in Buss's study, the average SD was 1,2 and 3. At the lower end, traits like kindness and intelligence had an SD of around 0.7 to 0.8. People essentially gave the same rank for these traits or picked one on either side.

So, generally speaking, people's mate preferences vary a bit, but they tend to focus quite tightly on a central tendency. Some might want chocolate cake and others fruit salad, but either way, everyone's looking at the dessert menu.

Not just a time and a place

As significant and impactful as the 1990 study was, its findings are now over 30 years old. Many things have changed since then, but what about our mate preferences? Research repeating this type of task in the US every other decade since World War II reveals remarkable rigidity in preferences over time (Boxer, Noonan & Whelan, 2015). A given trait might rank 8 out of 17 in one decade, rise to 6 in another, and swing downwards to 10. Still, overall, the correlation in mate preference ranking between 1949 and 2008 was r = .70 for men and .75 for women—incredibly consistent by psychological standards.

And even looking at cross-cultural differences in the modern day, you find that differences are a matter of degree. One culture might emphasize physical attractiveness more than another, but the overall picture is that they both care about it (Thomas et al., 2020).

The evolution of mate preferences

Why are human mate preferences so consistent? The answer is that our preferences impact our mate choices, which are not inconsequential. When choosing a long-term partner, we choose someone with whom we will merge our lives and potentially raise children. It's a huge investment of time, resources, and trust.

If our preferences were simply painted onto a blank canvas through learning and culture, suffering would follow. Many more people would find themselves tethered to someone with a high level of an arbitrary trait, yet are unkind, selfish, and incompatible with our way of life.

Instead, our mating psychology draws us toward partners who are kind, intelligent, and physically attractive, with levels similar to or greater than our own. We inherit this psychology from our ancestors, who used these traits to guide their mate choice. Those who chose more cooperative, fertile, and resilient partners than their less discerning cousins survived longer and reproduced more effectively, giving their "choosy genes" more representation in subsequent generations.

Understanding mate preferences to understand ourselves

Where does this leave us in the modern day? Well, it puts us in a place where denying the universal and consistent nature of mate preferences can actually be disempowering. By understanding the ultimate reasons why humans have evolved our particular preferences, we can think about the qualities we need to develop to become a more desirable option and a better prospective long-term mate.

It might also give us food for thought for what characteristics have been historically important but which we may currently be overlooking. Just because our ancestors used their mate preferences effectively doesn't mean that the latest generation can't "get it wrong," particularly when we have to navigate modern dating tools, such as online dating, using a stone-aged brain.

Facebook image: GaudiLab/Shutterstock

References

Boxer, C. F., Noonan, M. C., & Whelan, C. B. (2015). Measuring mate preferences: A replication and extension. Journal of Family Issues, 36(2), 163-187.

Buss, D. M., Abbott, M., Angleitner, A., Asherian, A., Biaggio, A., Blanco-Villasenor, A., ... & Yang, K. S. (1990). International preferences in selecting mates: A study of 37 cultures. Journal of cross-cultural psychology, 21(1), 5-47.

Thomas, A. G., Jonason, P. K., Blackburn, J. D., Kennair, L. E. O., Lowe, R., Malouff, J., ... & Li, N. P. (2020). Mate preference priorities in the East and West: A cross‐cultural test of the mate preference priority model. Journal of Personality, 88(3), 606-620.