Attention

Drawing a Fish—and Other Ways to Observe

Two essays found their way to me and both opened my eyes.

Updated March 1, 2024 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- Serendipity helps us connect the dots.

- Stopping to look requires time and purpose.

- Try 15-minute observation journals to explore the world around you.

I’m a believer in connecting the dots, even if they are years apart. Two dots struck me this week, essays that argue for deep observation. One, written in the early 1870s, sounds eerily like another, written in 2024.

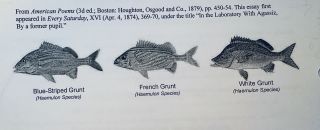

The first is an essay by a student of entomology who approached the renowned Harvard ichthyologist Dr. Louis Agassiz, for help in learning more about zoology. The result was an unexpected lesson in science and in life. In "The Student, the Fish and Agassiz" the student writes about an assignment from Agassiz—to observe a fish.

The professor describes how to preserve the fish (with a little alcohol in the tin tray), says he will check in later to hear what the student has learned, and leaves. After 10 minutes, the student has “seen all that could be seen in that fish” and looked for the professor, who was still gone.

Long story short, the student repeatedly returns to the fish and each time sees more. Every day, he reports to the professor who is pleased with the student’s progress, but says there is much more to be found. I think the student spent four days examining and at last drawing the fish to learn even more.

The lesson: concentration and time, description in words and drawing, and the skill of deep observation helped the student learn more about the fish than he thought possible.

The anonymous author, revealed later, was entomologist and paleontologist Samuel H. Scudder (1837-1911), who in his own career became well-known for his legendary work on butterflies, but is perhaps best remembered to laypeople for his fish essay.

The second article about 15-minute journals was in The New York Times Magazine, January 21, 2024. Anna Kode found herself on a subway one day after work—without a book and too tired to study her screen. Instead, she just looked, listened, and smelled what was around her, from a woman in a spiky hat, to untied—and tied—shoelaces, signs, and people snoring.

She realized how little attention she normally paid to the “mundane” around her. That experience convinced her to start doing “observation journaling,” to note what was around her, regardless of where. For 15 minutes a day, she wrote about what was around her, from people to sounds, odors to her own feelings. Instead of being upset at having to wait for another person, for an appointment, for the start of an event, she observed and “took in her surroundings.”

Kode hadn’t truly seen the worlds she lived in until she stopped to observe them deeply, just like the young entomologist 150 years before. That’s my goal for 2024—to learn to observe, from the mundane to the remarkable.